Decline in Productivity key to Japan s lost decade

Post on: 27 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Decline in Productivity key to Japans lost decade?

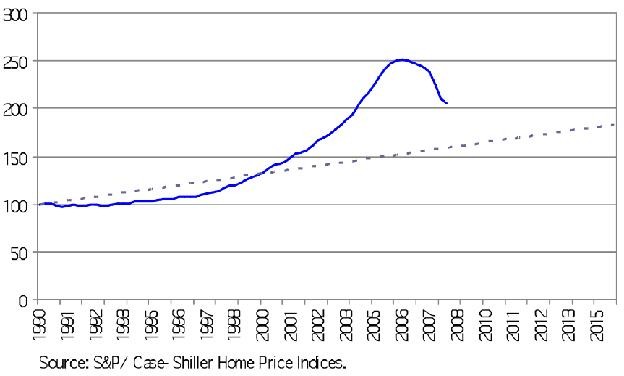

Whatever research I have read on Japans lost decade I always thought the reason for crisis was asset market boom (with rising real estate and equity prices), banks lending to the real estate companies and other zombie corporations. Once the house prices fell, all things collapsed. We are seeing the same events in US and other economies whose fin firms were linked to US housing markets. That is why we often compare the 2 events. And then the policy moves deepened the recession (though Japanese policymakers dont agree. see this as well )

In my quest to find anything on Japanese, I came across this paper from Edward Prescott and Fumio Hayashi. Here is what they say:

This paper examines the Japanese economy in the 1990s, a decade of economic stagnation. We find that the problem is not a breakdown of the financial system, as corporations large and small were able to find financing for investments. There is no evidence of profitable investment opportunities not being exploited due to lack of access to capital markets. The problem then and still today, is a low productivity growth rate. Growth theory, treating TFP as exogenous, accounts well for the Japanese lost decade of growth. We think that research effort should be focused on what policy change will allow productivity to again grow rapidly.

The authors look at whether there was a credit crunch for businesses and find nothing of the kind. Infact investment continued to increase for both large and small enterprises.

Growth theory gives no role to frictions in financial intermediation. To many this may appear a serious omission. It is natural to suspect that the collapse of bank loans that took place throughout the 1990s must have something to do with the output slump in the same decade. There is an emerging literature about Japan that asks (a) whether the decline in bank loans was a “credit crunch”— namely, a decline due to supply factors (such as the BIS capital ratio imposed on banks), and (b) if so, whether it depressed output by constraining investment. In Section 4 of the paper, we present evidence from various sources that the answer to the first question is probably yes, but the answer to the second question is no. That is, despite the collapse of bank loans, firms found ways to finance investment. This justifies our neglect of financial factors in accounting for the lost decade.

Instead it was fall in Total Factor Productivity furthered by reduction of work week length that led to slide in Japanese economy

Two developments are important for the Japanese economy in the 1990s. First and most important is the fall in the growth rate of total factor productivity (TFP). This had the consequence of reducing the slope of the steady-state growth path and increasing the steady-state capital-output ratio. If this were the only development, investment share and labor supply would decrease to their new lower steady-state values during the transition. But, the drop in the productivity growth alone cannot account for the near-zero output growth in the 1990s.

The second development is the reduction of the workweek length (average hours worked per week) from 44 hours to 40 hours between 1988 and 1993, brought about by the 1988 revision of the Labor Standards Law. In the most standard growth model, where aggregate hours (average hours worked times employment) enter the utility function of the stand-in consumer, a decline in workweek length does not affect the steady-state growth path because the decline is workweek length and employment enter the utility function separately, so that a shortening of the workweek shifts the level of the steady-state growth path down.

Hmmm. Towards the end the authors add that it was the expectation that productivity will rise that led to build up of bubble:

We said very little about the “bubble” period of the late 1980s and early 1990s, a boom period when property prices soared, investment as a fraction of GDP was unusually high, and output grew faster than in any other years in the 1980s and 1990s. We think the unusual pickup in economic activities, particularly investment, was due to an anticipation of higher productivity growth that never materialized.

This just made me sit up and think. Now we have another set of theory for Japans slump. And this makes quite a lot of sense. We really cant explain the decade long slump by just slow policies etc.

Unfortunately, the same idea does apply to US currently as well.

Krugman pointed out that US productivity was mainly because of financial services which had all disappeared. So the productivity is actually much lower than what was understood. We can argue that the US bubble was basically because people thought US economy productivity was high and would continue to rise. I dont know whether US productivity has declined in this crisis but with the financial service correction, it looks likely.

Then the usual idea that there is a credit crunch which is leading to low growth doesnt really apply as strongly. Richmond Fed Chief Lacker has always questioned whether credit has fallen because of lower demand or banks have cut credit because of poor balance sheet. He always favors the former. Liz Duke of Fed in her recent speech showed that small banks have continued to lend and the problem of low credit was mainly in large banks.

So now my new understanding of events in Japan and US is like this.

- Asset market boom (with rising real estate and equity prices) expecting productivity to rise continuously,

- Banks lending to the real estate companies (in US case mortgages and securities backed by the same).

- Once the house prices fell, the asset boom began to correct leading to wide correction in fin firms and non fin firms

- The key is if productivity declines and continues to decline. It is then the recession deepens. Prescott-Hayashi show this happened in Japan. Krugman suggest productivity driver in US has vanished. So we dont really know the status of US productivity as of now.

- The policymakers should strive to increase productivity levels or raise expectations of its rise as then only fin markets would improve. But raising productivity does not happen in a day. It takes years.

- In US case, it has evaporated so has to be generated from elsewhere. Same is the case with other finance driven economies as well. Obama plan to get some green technology inititatives etc are an attempt to generate productivity from elsewhere.

- Overall the situation does not really look promising.