What We Can Learn From Margin Levels In The Stock Market

Post on: 20 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

[Originally published 6/13/2014]

Investors with larger risk appetites often use leveraged strategies in their portfolio to amplify potential gains and take advantage of opportunities as soon as they present themselves. Borrowing funds at low interest rates and investing the money in investments that earn a higher rate of return allows sophisticated traders to enhance long-term performance at an accelerated pace.

Utilizing leverage to boost trading performance is commonly used in futures trading and executed by some of the biggest names on Wall Street. Hedge Fund guru Bruce Kovner famously charged $3,000 on his credit card to speculate on soybean futures. He watched as his investment climbed to $40,000 before crashing back down to $23,000, but marveled at how he was able to borrow money and realize triple digit gains over the original amount.

Leverage is accomplished by using margin. Investors can borrow money at a predetermined interest rate by using a margin account. The amount that can be loaned is determined by the amount of capital you have and the brokers margin ceiling. When used correctly, investors can boost returns by a considerable amount.

Heres how it works:

Lets say you have $100,000 and borrow an additional $40,000 at a rate of 6% and invest the combined total of $140,000. You decide to buy 2,800 shares of ABC at $50 a share. After one year, ABCs stock value is $55 a 10% gain. However, because you bought on margin, your gain is actually 11.60%. You gained an additional $1,600 after paying back the loan of $40,000 and the interest of $2,400.

2800 * $55 = $154,000 $40,000 $2,400 = $111,600

Margin levels in the stock market fluctuate according to overall sentiment. During bull markets, margin debt rises as investors look to amplify gains and vice versa during bear markets. Leverage however, impacts volatility. When market behaviors change, the amount of leverage being used can cause wide swings in price movements and trigger selling cascades.

Margin in a Historical Context

Investment activity leading up to the Great Depression reveals how impactful margin lending can be. During the 1920s, margin maintenance requirements were only a fraction of what they are today; a mere 10% in most cases. That meant that an investor could leverage $9 for every $1 they had in the market. When the market finally crashed and brokers began to call margins, they discovered that most of their clients money was in the stock market and the only way to recoup losses was to sell stock. The domino effect of selling and depressing prices only to create more margin calls was one of the major causes of the crash in 1929.

Studies have shown that the long-term impact of margin calling during the Great Depression meant that financial institutions lacked the capital necessary to loan out for economic expansion. The lack of available credit caused businesses to crumble and consumers to stop spending which only deepened the crisis.

Stock market bubbles and high levels of margin debt are correlated with market crashes. As margin expands, stock performance must also rise in order to make the lending pay off. Unrealistic expectations and a disconnect from risk allows margin levels to trickle ever higher until the market simply cant produce high enough returns and a massive sell-off and de-leveraging begins.

A more recent example of this effect can be seen back in 2008 during the mortgage bubble. As early as November of 2006, margin debt climbed 10% month-over-month to $270 billion sending the first stirrings of collapse. In January of 2007, NYSE margin debt was $285.6 billion and by July it was $353 billion soaring over 22% in just 5 months. It peaked in August of 2007 at $381 billion before the sub-prime mortgage market began to crumble sending stocks lower and forcing a panic de-leveraging that set off a recession.

Current Margin Levels and Warning Signs

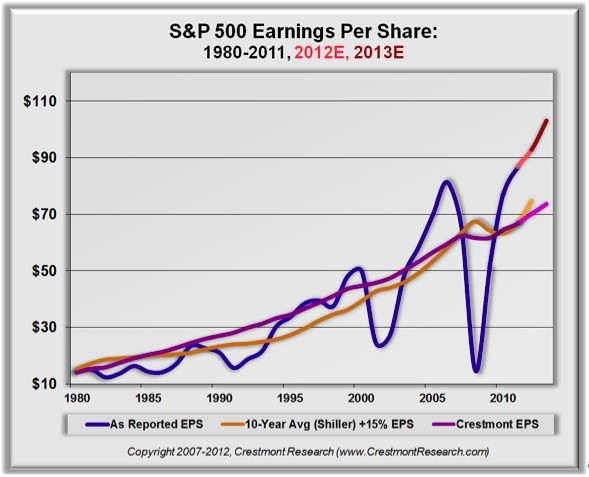

Today, margin debt levels are at record high figures and have been since April of last year. Despite climbing P/E ratios, margin debt, and the length of the bull market, market indices continue to hit new highs. The similarities between this market and those of the past are eerily similar and investors should take notice of the warning signs.

In April of 2013, margin debt levels broke the previous record at $384 billion while total investor net worth (calculated as Free Credit Cash plus Credit Balances in Margin Accounts minus Margin Debt) sunk to a record low since 2000 of -$106 billion meaning that money is more leveraged than ever. According to data posted by the NYSE, margin debt levels appeared to have peaked in February this year at a staggering $465.7 billion. March and April have trended downwards somewhat to $437 billion that some analysts say indicate an impending correction.

Late last year, Deutsche Bank released a report called, Red flag! The curious case of (NYSE) Margin Debt. It surveyed over 700 global asset managers and revealed just how much leverage is affecting expectations. The results found that 78% of all defined-benefit pension plans required returns of at least 5% to meet commitments while 19% needed as much as 8%. As the stock market rises and debt levels along with it, price volatility becomes greater and greater and a less severe market sell-off is needed to trigger a collapse.

Comparing the current markets debt levels to past levels reveal a correlation with one statistic in particular. A month-over-month change in margin debt of 10% or more seems to be a trigger for upcoming crashes. Heres a look at the market since 1999 and associated 10% month-over-month margin debt increases.

Apr 1999 MoM change over 10%

Nov 1999 MoM change over 10%

Dec 1999 MoM change over 10%

Mar 2000 Margin Debt Peak

Mar 2000 S&P 500 Peak

Nov 2006 MoM change over 10%

Apr 2007 MoM change over 10%

Jul 2007 Margin Debt Peak

Oct 2007 S&P 500 Peak

Jan 2013 MoM change over 10%

Feb 2014 Margin Debt Peak

While correlation doesnt necessarily equal causation, the figures are hard to ignore out of hand. Recognizing that crossing the threshold of the critical margin debt growth of 10% may suggest that a correction is near, investors should start de-leveraging and hedging their positions now.

De-Leveraging and Managing Risks

After the global crisis that rocked markets back in 2008, it was thought that a great de-leveraging would occur in order to pare down risks. Fast forward to 2014 and the aggregate de-leveraging has still not occurred. Consumers have de-levered, but borrowing by the U.S. government offset it. As of the 1 st quarter this year, total U.S. debt (public + private) to GDP stands near 350%.

De-leveraging happens in one of three ways: pay down debt, grow out of it, or inflate your way out of it. While the U.S. economy is growing, the amount of debt circulating is growing even faster. While some de-leveraging took place in 2011 and 2012, were back up to record highs as people are ignoring the warning signs that high leverage creates.

As the bull market continues to inflate P/E ratios and demand ever higher expectations, investors are looking for ways to manage risk. There are several ways to mitigate risks by de-levering your portfolio without selling out of all your positions.

- Diversify Its something youll hear repeated in almost every facet of portfolio management and for good reason. Staying diversified across multiple sectors and companies helps insulate you from down markets by spreading out risk. Sectors like utilities are often negatively correlated to the S&P 500 so as it declines, those types of stocks will actually rise in value.

- Utilize Options Selling covered calls are a good way to manage risk by taking in a premium and lowering your break-even point in the stock you own. If you want an additional hedge, you could also use the premium you received from selling the call to purchase a put as well. For a reduced price, you can effectively limit downside risk to single digit losses even if another crash like the one in 1929 were to happen again.

- Short Stocks Shorting a stock will allow you to take advantage of downturns but are extremely risky unless you hedge shorts with options. Shorting a stock and buying a call will protect you from surprising upsides that could otherwise force you to buy back stocks at a much higher price than what you sold it short for.

No bull or bear market is everlasting. Every market operates in a dynamic environment and subject to unforeseen changes. Investors should keep a close watch on margin accounts and rely on options as a source of leverage rather than borrowed funds. Option buying and selling comes with calculable costs and risks and allows you to invest without worrying about your broker stepping in and selling stock to cover losses.