The Great Race ETFs v

Post on: 12 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

New Opportunities for Indexing Complicate Investors’ Choices; Picking the Right Market ‘Slice’

Eleanor Laise Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Updated Nov. 5, 2005 12:01 a.m. ET

One of the simplest strategies for socking away savings — buying into an index fund that simply tries to match the performance of, say, the S&P 500 — is getting trickier.

Currently nearly 10% of all long-term mutual-fund assets are in index funds, and little wonder: Not only are the fees low, but the indexes they track usually have long, reassuring performance records — something investors find comforting.

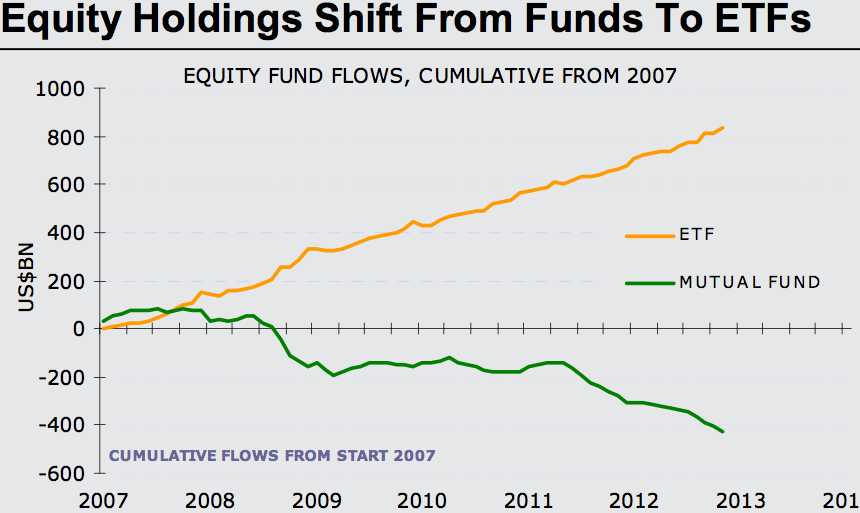

But in the past few years a racy newcomer, exchange-traded funds, have started opening up significant new investment strategies. While ETFs behave much like traditional index mutual funds, they have key differences. The main one: Unlike mutual funds, they trade on an exchange, just like a stock.

As a result of the boom, mom-and-pop investors are gaining access to a growing array of different exchange-traded index funds. This year alone, more than 30 new ETFs have been launched, tracking everything from clean-energy stocks to the nanotechnology industry.

According to Boston-based Financial Research Corp. ETFs now account for nearly one-third of all assets devoted to so-called passive investing (a term for investments like index funds), up from 9% in 2000. In less than three years, the total number of ETFs has jumped nearly 70%, to 185, while the number of index funds has remained relatively flat. ETFs have even started popping up in 401(k) plans.

A key driver in the popularity of ETFs is the failure by many mutual-fund managers to beat the market for extended periods of time, even as they collect big management fees. Instead, many advisers have turned to a strategy of lower-cost index funds, and increasingly, ETFs.

ETF’s rising attractiveness also stems from the mutual-fund trading scandals of recent years. Traditional mutual funds are priced only once a day, after the market closes — and some rapid-fire traders used strategies designed to profit from the fact that prices could get out-of-date. Because ETFs are priced like stocks, meaning they trade throughout the day, they aren’t vulnerable to the rapid-trading strategy.

ETFs also attract investors who want to dart in and out of the market more quickly. But their costs and tax implications are different from index funds. Make the wrong choice, and costs can add up over time.

In general, traditional index funds are best for people who make regular contributions to their account. That is because you must pay a commission to buy or sell an ETF, while index funds often cost nothing to trade. ETFs, by contrast, tend to be better for investors who want to make bets on narrow market segments, trade during the day, or use sophisticated trading strategies.

For instance, because ETFs trade just like stocks, they can easily be sold short — meaning investors can bet that an index will drop by selling borrowed shares, then buying them back when the price falls. ETFs also slice the market more finely than traditional index funds, offering an alternative way to invest in, say, Malaysian stocks or a narrow industry that typically has lower costs than a similar but actively managed fund.

The biggest ETFs and index funds, however, are those that track broad market indexes like the S&P 500. Because these types of funds are often core portfolio holdings, it is key for investors to weigh the costs and performance of a conventional index fund against rival ETFs.

Here is a guide:

Start by comparing expenses, says Dan Culloton, a senior analyst at fund tracker Morningstar. Many ETFs have very low expenses, partly because they don’t have to pay for account maintenance or print reams of mailings like mutual funds do. The median ETF annual expense ratio is 0.3%, according to Morningstar. The median no-load index fund’s expense ratio is slightly higher, at 0.35%.

For most average investors looking to put away a few hundred dollars a month, low-cost traditional mutual funds will be the better option, Mr. Culloton says. Those planning to make one large lump-sum investment or are investing inside a 401(k) may have reason to consider an ETF. Some 401(k) plans bundle ETF trades, reducing commission costs.

Investors can find both broad-market ETFs and index funds with low expenses. When ETF trading commissions are considered, index funds are often less expensive for investors making regular account contributions. The Standard & Poor’s Depository Receipts. or SPDR, the iShares S&P 500 Index Fund and funds from Fidelity and E*Trade all track the S&P 500 and charge expenses of 0.1% or less. People willing to commit $100,000 to the Fidelity fund will pay just 0.07%, slightly less than the competing ETF options.

The Vanguard 500 Index Fund — the largest of the bunch — charges considerably more. For small investors, its expenses total 0.18%.

More exotic ETFs can be far pricier. iShares products that track South Korean, South African and Taiwanese stocks, for example, all charge 0.74%.

Investors also must consider where their accounts are maintained. If you are investing through a fund supermarket like Schwab, for instance, you may pay a transaction fee to buy a Vanguard index fund that is higher than the commission on an ETF.

ENLARGE

Other costs are less obvious but can still eat into returns. Because an ETF trades like a stock, its market price can move away from its per-share net asset value (essentially, assets minus liabilities). It is usually no problem in heavily-traded ETFs like SPDR. But in some cases an investor might end up buying at a premium, then having to sell at a discount. Conventional index funds always trade at net asset value.

Tax Consequences

There is a perception that ETFs are more tax-efficient than index funds. While they do have some advantages, the idea that ETFs should never pay capital-gains distributions is a myth, says Jim Ross, co-head of the ETF business at State Street Global Advisors.

On the other hand, people who are especially tax sensitive might consider an entirely different animal, a tax-managed fund, says Larry Swedroe, a principal at Buckingham Asset Management in St. Louis. For instance, the Vanguard Tax-Managed Growth and Income Fund is essentially an S&P 500 index fund, but it sometimes shifts away from that strategy slightly to gain some sort of tax advantage. Over the past five years it has been more tax-efficient than its ETF rivals.

The fact that ETFs trade on a stock exchange generally does give them some tax advantages. The reasons are complex but it has to do with the fact that, unlike mutual funds, ETFs don’t need to sell their holdings to meet shareholder redemptions, thus avoiding some capital-gains issues.

Of course, most index funds are pretty good at minimizing the tax hit, too. Over the past five years, investors in the Vanguard 500 Index Fund lost about 0.4% of their assets to taxes annually, according to Morningstar, while investors in the iShares S&P 500 and the SPDR ETF lost about 0.6%.

A more important consideration may be the tax on dividend payouts.

A fund must hold a stock for roughly two months surrounding the time when dividends are decided, if the payout is to qualify for the lower dividend tax rate that maxes out at 15%; otherwise it can be taxed at a higher rate.

This rule has caused particular problems for some ETFs: Last year, 83% of the iShares S&P 500 Index Fund dividends qualified for the lower tax rate, compared with 100% for the Vanguard 500 Index Fund.

Performance

In broad market categories, conventional index funds’ returns often stack up well against ETFs on a pre-tax as well as an after-tax basis.

In the five years ending Oct. 31, S&P 500 funds from Fidelity and Vanguard posted better after-tax returns than their ETF rivals, the SPDR and the iShares S&P 500, according to Morningstar. In addition, their pre-tax returns were very close to the ETFs’.

Though they don’t track the same index, the iShares Russell 3000 Index ETF and the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund both offer exposure to a broad swath of U.S. stocks. The Vanguard fund’s five-year returns beat the iShares’ performance both before and after tax. Among funds that track the MSCI EAFE Index (a broad foreign-stock index), conventional offerings from Fidelity and Vanguard have delivered three-year pre-tax and after-tax performance nearly identical to the iShares MSCI EAFE Index Fund — and have lower expenses.

Investors interested in narrower market segments may find more selection and better returns in ETFs. The iShares S&P SmallCap 600/Barra Value ETF and its growth counterpart have posted better pre-tax and after-tax three-year returns than its traditional fund competition from ProFunds — and they are much less expensive.

And if you want a passively managed fund that tracks the price of gold or South Korean stocks, an ETF is your only option. But investors need to remember that some sector and single-country ETFs can be very concentrated in just a few holdings, says Morningstar’s Mr. Culloton.

The iShares MSCI Austria Index Fund. for example, had 82% of assets in 10 stocks as of Sept. 30.