The Agile System Development Life Cycle (SDLC)

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

This article covers:

1. The Scope of Life Cycles

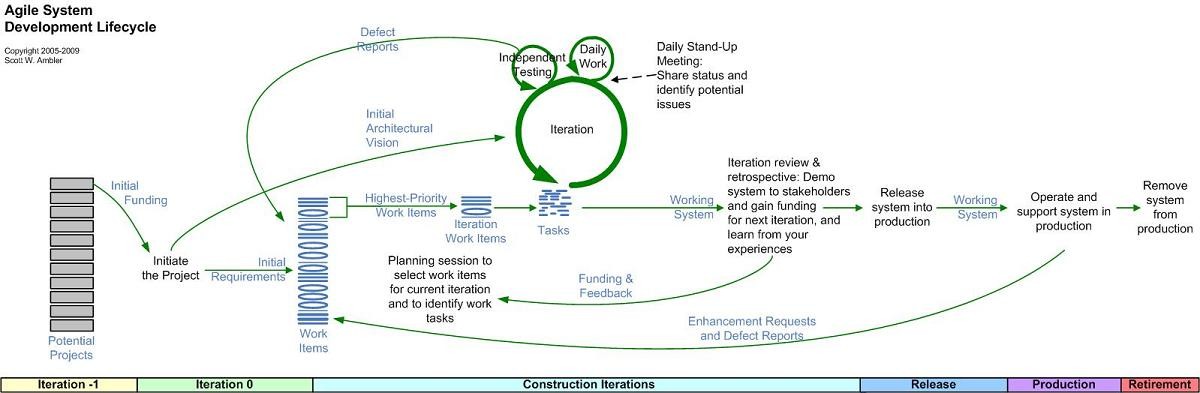

As we described in the book The Enterprise Unified Process (EUP) the scope of life cycles can vary dramatically. For example, Figure 1 depicts the Scrum construction life cycle whereas Figure 2 depicts an extended version of that diagram which covers the full system development life cycle (SDLC). Later in this article we talk about an Enterprise IT Lifecycle. My points are:

- Solution development is complicated. Although it’s comforting to think that development is as simple as Figure 1 makes it out to be, the fact is that we know that it’s not. If you adopt a development process that doesn’t actually address the full development cycle then you’ve adopted little more than consultantware in the end. My experience is that you need to go beyond the construction life cycle of Figure 1 to the full SDLC of Figure 2 (ok, Retirement may not be all that critical) if you’re to be successful.

- There’s more to IT than development. To be successful at IT you must take a multi-system, multi-life cycle stage view as we show in the discussion of the Enterprise IT Lifecycles. The reality is that organizations have many potential endeavours in the planning stage (which I’ll call the Concept Phase in this article), many in development, and many in production .

Figure 1 uses the terminology of the Scrum methodology. The rest of this article uses the terminology popularized in the mid-1990s by the Unified Process (Sprint = Iteration, Backlog = Stack, Daily Scrum Meeting = Daily Meeting) and also adopted by Disciplined Agile Delivery (DAD). Figure 1 shows how agilists treat requirements like a prioritized stack. pulling just enough work off the stack for the current iteration (in Scrum iterations/sprints are often 2-4 weeks long, although this can vary). At the end of the iteration the system is demoed to the stakeholders to verify that the work that the team promised to do at the beginning of the iteration was in fact accomplished.

Figure 1. The Scrum construction life cycle.

The Scrum construction life cycle of Figure 1. although attractive proves to be clearly insufficient in practice. Where does the product backlog come from? Does it get beamed down from the Starship Enterprise? Of course not, it’s actually the result of initial requirements envisioning early in the project. You don’t only implement requirements during an iteration, you also fix defects (disciplined agile teams, particularly working at scale, may have a parallel testing effort during construction iterations where these defects are found), go on training, support other teams (perhaps as reviewers of their work), and so on. So you really need to expand the product backlog into a full work items list. You also release your system into production. often a complex endeavor.

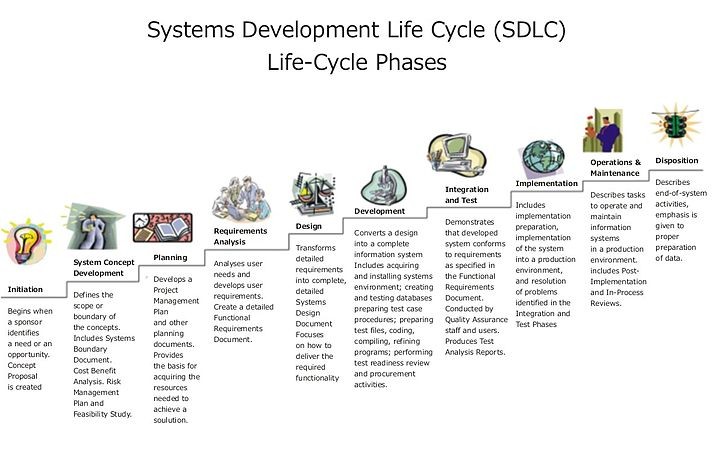

A more realistic life cycle is captured Figure 2. overviewing the full agile SDLC. This SDLC is comprised of six phases: Concept Phase. Iteration 0/Inception. Construction. Transition/Release. Production. and Retirement. Although many agile developers may balk at the idea of phases, perhaps Gary Evan’s analogy of development seasons may be a bit more palatable, the fact is that it’s been recognized that Extreme Programming (XP) does in fact have phases (for a diagram, see XP life cycle ).

Figure 3 depicts the agile/basic lifecycle described by the Disciplined Agile Delivery (DAD) framework. This lifecycle originated from earlier versions of Figure 2. Because DAD isn’t prescriptive it supports several lifecycles. The lifecycle of Figure 3 is DAD’s Scrum-based, or basic, agile delivery lifecycle but it also supports a lean/Kanban type of lifecycle and a continuous delivery lifecycle (shown in Figure 4 ) as well. The idea is that your team should adopt the lifecycle that makes the most sense for the situation that you face.

On the surface, the agile SDLC of Figure 5 looks very much like a traditional SDLC, but when you dive deeper you quickly discover that this isn’t the case. This is particularly true when you consider the detailed view of Figure 2. Because the agile SDLC is highly collaborative, iterative, and incremental the roles which people take are much more robust than on traditional projects. In the traditional world a business analyst created a requirements model that is handed off to an architect who creates design models that are handed off to a coder who writes programs which are handed off to a tester and so on. On an agile project, developers work closely with their stakeholders to understand their needs, they pair together to implement and test their solution, and the solution is shown to the stakeholder for quick feedback. Instead of specialists handing artifacts to one another, and thereby injecting defects at every step along the way, agile developers are generalizing specialists with full life cycle skills.

2. The Concept Phase. Pre-Project Planning

Concept Phase activities can and should be as agile as you can possibly make it you should collaborate with stakeholders who are knowledgeable enough and motivated enough to consider this potential project and invest in just enough effort to decide whether to consider funding the effort further.

3. Inception /Warm Up: Project Initiation

The first week or so of an agile project is often referred to as Iteration 0 (or Cycle 0) or in The Eclipse Way the Warm Up iteration. Your goal during this period is to initiate the project by:

- Garnering initial support and funding for the project. This may have been already achieved via your portfolio management efforts. but realistically at some point somebody is going to ask what are we going to get, how much is it going to cost, and how long is it going to take. You need to be able to provide reasonable, although potentially evolving, answers to these questions if you’re going to get permission to work on the project. You may need to justify your project via a feasibility study .

- Actively working with stakeholders to initially model the scope of the system. As you see in Figure 6. during Iteration 0 agilists will do some initial requirements modeling with their stakeholders to identify the initial, albeit high-level, requirements for the system. To promote active stakeholder participation you should use inclusive tools. such as index cards and white boards to do this modeling our goal is to understand the problem and solution domain, not to create mounds of documentation. The details of these requirements are modeled on a just in time (JIT) basis in model storming sessions during the development cycles .

- Starting to build the team. Although your team will evolve over time, at the beginning of a development project you will need to start identifying key team members and start bringing them onto the team. At this point you will want to have at least one or two senior developers, the project coach/manager, and one or more stakeholder representatives.

- Modeling an initial architecture for the system. Early in the project you need to have at least a general idea of how you’re going to build the system. Is it a mainframe COBOL application? A .Net application? J2EE? Something else? As you see in Figure 6. the developers on the project will get together in a room, often around a whiteboard, discuss and then sketch out a potential architecture for the system. This architecture will likely evolve over time, it will not be very detailed yet (it just needs to be good enough for now), and very little documentation (if any) needs to be written. The goal is to identify an architectural strategy, not write mounds of documentation. You will work through the design details later during development cycles in model storming sessions and via TDD .

- Setting up the environment. You need workstations, development tools, a work area. for the team. You don’t need access to all of these resources right away, although at the start of the project you will need most of them.

- Estimating the project. You’ll need to put together an initial estimate for your agile project based on the initial requirements, the initial architecture, and the skills of your team. This estimate will evolve throughout the project.

Figure 6. The Agile Model Driven Development (AMDD) life cycle.

The 2013 Agile Project Initiation Survey found that the average time to initiate an agile project took 4.6 weeks. Figure 7 depicts the range of initiation periods. Differences are the results of the complexity of the domain/problem space, technical complexity of what you’re trying to accomplish, availability of stakeholders, ability of stakeholders to come to agreement as to the scope. and ability of the team to form itself and to obtain necessary resources.

Figure 7. How long did it take to initiate an agile project?

4. Construction Iterations

During construction iterations agilists incrementally deliver high-quality working software which meets the changing needs of our stakeholders, as overviewed in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Agile software development process during a construction iteration.

We achieve this by:

Collaborating closely with both our stakeholders and with other developers. We do this to reduce risk through tightening the feedback cycle and by improving communication via closer collaboration.

Implementing functionality in priority order. We allow our stakeholders to change the requirements to meet their exact needs as they see fit. The stakeholders are given complete control over the scope, budget, and schedule they get what they want and spend as much as they want for as long as they’re willing to do so.

Analyzing and designing. We analyze individual requirements by model storming on a just-in-time (JIT) basis for a few minutes before spending several hours or days implementing the requirement. Guided by our architecture models, often hand-sketched diagrams, we take a highly-collaborative, test-driven design (TDD) approach to development (see Figure 9 ) where we iteratively write a test and then write just enough production code to fulfill that test. Sometimes, particularly for complex requirements or for design issues requiring significant forethought, we will model just a bit ahead to ensure that the developers don’t need to wait for information.

Ensuring quality. Disciplined agilists are firm believers in following guidance such as coding conventions and modeling style guidelines. Furthermore, we refactor our application code and/or our database schema as required to ensure that we have the best design possible.

Regularly delivering working solutions. At the end of each development cycle/iteration you should have a partial, working solution to show people. Better yet, you should be able to deploy this solution into a pre-production testing/QA sandbox for system integration testing. The sooner, and more often, you can do such testing the better. See Agile Testing and Quality Strategies: Discipline Over Rhetoric for more thoughts.

Testing, testing, and yes, testing. As you can see in Figure 10 agilists do a significant amount of testing throughout construction. As part of construction we do confirmatory testing, a combination of developer testing at the design level and agile acceptance testing at the requirements level. In many ways confirmatory testing is the agile equivalent of testing against the specification because it confirms that the software which we’ve built to date works according to the intent of our stakeholders as we understand it today. This isn’t the complete testing picture: Because we are producing working software on a regular basis, at least at the end of each iteration although ideally more often, we’re in a position to deliver that working software to an independent test team for investigative testing. Investigative testing is done by test professionals who are good at finding defects which the developers have missed. These defects might pertain to usability or integration problems, sometimes they pertain to requirements which we missed or simply haven’t implemented yet, and sometimes they pertain to things we simply didn’t think to test for.

Figure 9. Taking a test first approach to construction.