Stock options backdating What you need to know

Post on: 11 Август, 2015 No Comment

With the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of California confirming that it’s investigating Apple’s backdating of stock options. it’s clear that the issue won’t fade away any time soon. For Mac users more comfortable with silicon chips than securities rules, it may be unclear just what’s at issue here. With that in mind, here’s an overview of backdating and when it runs afoul of regulators.

What is backdating and how does it work?

The practice involves stock options. A company promises a worker the right to buy a share of of stock at a specific price, called the strike price. The strike price is typically tied to the value of the stock on a certain date—the hiring date for an employee, for example.

Usually, as a company’s shares increase in value, so do any options issued. Say an employee gets a stock option with a strike price of $10. That option is currently worth nothing. If the employee is able to exercise that option by the time the stock’s trading at $15, that employee’s option is now worth $5.

However, if the employee’s original stock option was backdated to a period where their company’s stock was trading at $8, by the time the employee exercises their option, that option is now worth $7. If that difference seems slight, imagine it multiplied by thousands—or even millions—of options.

Is that illegal?

No—in fact, companies often do it as a way to lure top talent. “Backdating is totally legal if you disclose that it’s done,” said BusinessEdge Solutions compliance expert Phil Dina. “Investors have a right to know all the financial data of the company.”

Backdating becomes an issue when companies fail to let shareholders and regulators know that it’s taking place. The reason: Options are considered part of compensation, and if the company’s not accurately reporting how it’s compensating its employees, it’s not giving investors a complete financial picture. At the most basic level, Dina says, improperly backdating stock options is a way for companies to overstate their assets and understate their expenses.

Is Apple the only company under investigation?

Hardly. According to Patrick Taylor, CEO of options-monitoring software maker Oversight Systems, there have been at least 120 public companies that have come under scrutiny in the last year. These companies include Applied Micro Circuits, Electronic Arts, Foundry Networks, Intuit McAfee, and Steve Jobs’ other company, Pixar.

Why the sudden increase in backdating probes?

Because of changes in the law. First, the U.S. tax code limits a company’s ability to deduct some executive pay once it exceeds $1 million annually. Subsequently, compensating employees with options was a way to save on taxes for both the company its employees, as the proceeds from exercising stock options are eligible only for the 15-percent capital gain tax rate. Thus, companies had healthy incentives to load compensation packages with stock options.

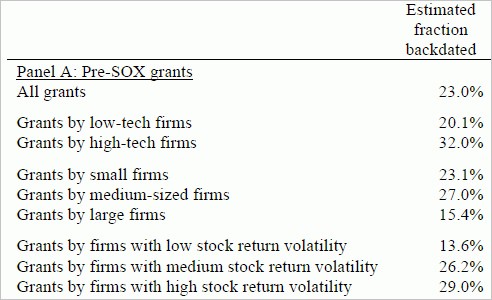

Second, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 required companies to report stock option grants within two days. The University of Michigan found that nearly a quarter of stock options were still reported late, often to the financial benefit of the options grantee.

Finally, the U.S. government began requiring companies to report stock options as an expense whenever options were granted or exercised as of fiscal year 2006.

As a result, companies’ net incomes may be affected by the new expense. For example, Intel reported $7.5 billion in earnings in 2004, but had the company had to account for the expense of options that were either granted or exercised, its earnings would have plunged to $1.3 billion.

So: the U.S. government gives companies a reason to favor stock options as compensation. But it’s now narrowed the window for reporting that compensation, and it’s now requiring it to be accounted for in a way that could make companies look like their earnings have shrunk.

What has Apple done?

Most of what we know so far has come directly from the company’s own disclosures. In June 2006, Apple announced that an internal probe had found some irregularities in some option grants issued between 1997 and 2001. Among those irregularities—a grant to its CEO, Jobs.

When Apple made the announcement, it also released a statement from Steve Jobs that read, in part, “We are proactively and transparently disclosing what we have discovered to the SEC. We are focused on resolving these issues as quickly as possible.”

Four months later, Apple said a special committee had found irregularities in 15 of the grants made between 1999 and 2002 —6 percent of the total grants issued in that period. Fred Anderson, who had been Apple’s chief financial officer from 1996 to 2004, resigned from his seat on the company’s board of directors. In a statement, Apple said it found no misconduct by its current senior management team, but expressed “serious concerns” about the actions of two unnamed former senior execs. More significant from a public perception standpoint, the internal investigation found that Jobs was aware that favorable grant dates had been selected but didn’t receive or benefit from those grants and was “unaware” of the accounting implications.

In late December, Apple disclosed more backdating-related news. again clearing current executives and taking an $84 million charge on its restated earnings.

So why is Apple still under federal scrutiny?

The answer may be in a Wall Street Journal report from earlier this month. According to the Journal. regulators are looking into a falsely dated grant of 7.5 million options to Steve Jobs. The grant was originally approved in August 2001, though Apple’s board didn’t approve it until December of that year when the company’s stock was trading $3 a share higher than in August. More troubling, Apple misdated the grant’s approval, linking it to an October 2001 board meeting that never actually took place.

So what happens next for Apple?

What will help or hurt any company enmeshed in a backdating probe is how its actions look to the government and to shareholders.

“Was (the backdating) intentional or was it an oops?,” Dina said. “That makes a big difference from regulatory and public perspectives. If the public feels they’ve been taken advantage of, it’ll accelerate in a hurry. It really depends on how (improper backdating) is perceived—was it maliciously done and something done to hide it?”

The public typically sits up and takes notice of improper backdating when it begins to understand the financial impact that practice had, Dina added. “John Q. Public doesn’t understand the money involved—it’s just a number. If you maybe boil this down to what it means to a share price—how maybe the stock would have been worth more, or how much value your holdings have lost [since the probe]—that’s when someone does the magic calculation. You have to wait until it becomes real to people losing money.”

One factor may help Apple’s standing in the court of public opinion, at any rate: its assertion that Steve Jobs wasn’t aware of the legal implications in the company’s back-dating processes.

Apple has emphasized Jobs’ distance from back-dating improprieties since it first admitted to them last June. The statements it issued in June, October and December stressed that Jobs hadn’t personally profited from the improperly-backdated options.

“The situation for Jobs would be far worse if it was shown that he knew about the backdating and that he had personally benefited from option backdating,” corporate governance attorney Robert Brighton said.

SEC filings show that in 2003, Jobs exchanged two options grants for 5 million shares of restricted stock worth approximately $75 million. The shares split, and last March, Jobs was eligible to exercise his now-10 million options. He sold half for $295.7 million.

However, Apple spokesperson Steve Dowling told the Washington Post that Jobs didn’t directly benefit from exercising those options because he was prohibited from selling the stock for another three years. Whether this argument will hold up under regulatory and public scrutiny remains to be seen.

Paul Hodgson, a compensation expert with The Corporate Library, is skeptical. “To claim that (Jobs) did not profit from backdated options because he surrendered them is untrue—whether he knew these were backdated or not—because he surrendered them for their equivalent value in restricted stock which he still holds,” Hodgson said. “Also, if he knew that others’ options were being backdated, might he not have suspected that his were?”

The second factor helping Apple: it has positioned the problematic backdating practices as a past problem. Although Apple has not explicitly linked the names of departed executives to falsified board meeting records currently drawing regulatory scrutiny, the company had cited “serious concerns” about ex-employees’ actions in October in a statement about its ongoing probe into its backdating.

Placing the emphasis on departed executives’ actions helps the company now. “In a practical sense, it helps Apple to remove what they say was the source of the problem so that they can move on,” Brighton said.

Nevertheless, Apple faces more than just a federal probe into its backdating practices. A group of shareholders is suing the company. alleging that improper backdating has harmed Apple financially.

[ Lisa Schmeiser is a writer whose work has appeared in Macworld and Investors Business Daily. ]