Long Calls (Bullish Options Strategy)

Post on: 18 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Long Calls — Bullish Options Strategy

When To Use

When one is moderately to aggressively BULLISH and expecting STABLE or EXPANDING implied volatility conditions.

Summary

The Long Calls strategy is the most basic options strategy and it involves the buying of Call options — at an appropriate strike price and of an appropriate expiration term.

A Call buyer almost always possesses a bullish bias towards near term action on the underlying asset. Often, s/he also desires an expansion, or at least stability, in the level of implied volatility on the relevant options. While a bullishly biased trader (and possibly even a trader with a neutral bias) can finesse his/her level of aggression in the trade by choosing calls that possess a preferred state of moneyness, a bearishly biased trader will not find much use for this strategy.

The long calls strategy is often used as a substitute to owning stock. This is because it provides the trader with nearly all of the potential profit on the upside while limiting the potential loss on the downside. Accordingly, it is often used as a tool of leverage or, alternatively, as a means of making a cautiously bullish trade.

Directional Bias

Long Calls are generally utilized when the trader is moderately to aggressively bullish on the underlying stock. Occasionally, this strategy might even be appropriate if the trader has a neutral bias.

Rise in Underlying Price: Positive Effect

The primary desire of the call buyer is for a rally in the underlying stock. The farther the stock rallies, and the faster that it does so, the better for the long calls position.

Relatively Small Move in Underlying Price: Usually Negative Effect

A trader with a neutral outlook (expectation of range-bound trading action) on the underlying might usually avoid buying calls, although there are special circumstances wherein this action might be warranted (we’ll touch upon such circumstances later in this piece).

Decline in Underlying Price: Negative Effect, but Losses are Limited

A trader who is expecting a decline in a stock will not use a long calls position. However, a trader who holds an existing position in long calls will feel secure in the knowledge that even if his bullish opinion is later found out to have been wrong, his/her losses are limited, regardless of how far the underlying stock falls.

Risk vs. Reward

Often, a trader uses this strategy in order to leverage his buying power. A small capital outlay provides the trader with a potential profit that is many times the initial investment (the premium paid to purchase the call option). Furthermore, this initial investment is the extent of his risk in the trade.

The trader cannot lose more than this relatively small amount, no matter how far the underlying stock declines. However, due to factors such as time decay and implied volatility conditions, there is usually also a good statistical chance that a loss will occur, unless there is a timely rally in the stock.

In the following segment, we’ll analyze the potential profitability — given various outcomes in the price of the underlying stock — of using this strategy; we’ll also investigate how using this strategy compares with simply owning the underlying stock.

Profit & Loss Analysis

Long calls gain in value as the underlying rises in price. Since the underlying can theoretically increase in price infinitely, so can the value of a call option on it. The profit (at expiration) of a call option is calculated as follows:

Profit at Expiration: Stock Price — Strike Price — Premium Paid

Illustration. Assume a call option with a strike price of $50.00 has been purchased at a price $5.50. There are 6 months to expiration and implied volatility is calculated to be 30%. Now, let us assume that the option expires with the underlying trading at $60.00. If so, the profit at expiration would be: $60.00 -50.00 -5.50 = $4.50.

The following diagram illustrates the intricacies of the profit and loss chart for the call option used in the example.

Since the value of a call option can theoretically increase infinitely, the maximum profit attained on such a position can do so as well. Moreover, the value of the call option can only decrease to zero — it cannot have a negative value — and therefore the maximum loss attainable is equivalent to the premium paid on the purchase of the call.

It is important to decipher the breakeven point(s) in an options trade (in any trade, for that matter) so that areas of profitability can be ascertained. So, let’s take a look at how the breakeven point, as well as the maximum profit and maximum loss amounts, of a Long Calls position can be calculated.

Breakeven Point: Strike Price + Premium Paid

In the case of the long calls strategy, calculation of the breakeven price is simple. The cost of the call option is added to the strike price, and the resulting figure is the breakeven price. In the example above, ($5.50 + 50.00 =) $55.50 is the breakeven price. Therefore, it is the goal of the long calls owner to find the underlying trading at least as high as the breakeven point (so that she can, at worst, recoup her investment).

Max Profit: Unlimited, on the upside

A call option expires with a profit as long as the underlying stock closes above the breakeven price. The farther the underlying moves above the breakeven price, the higher the absolute profit on the call option.

Max Loss: Limited, to the premium paid

As mentioned previously, probably the biggest benefit of the call option strategy is the fact that the maximum loss that can be attained is amount of the premium paid on purchasing the position. This maximum loss is attained if the underlying stock is trading below the strike price when the call option expires. If the option expires with the underlying stock trading in between the strike price and the breakeven point, the trader still ends up with a loss, but one of a smaller magnitude.

Comparison with Long Stock

So, how does the long calls strategy stack up to outright ownership of the stock? When would a trader want to choose one or the other? Let’s briefly explore the answers to those questions:

The following diagram compares the payoffs from a long stock position, which has a purchase price of $50.00, and a long calls position, which has a strike price of $50.00 and a cost of $5.50.

The following are a few facts that can be gathered from this illustration:

The breakeven (see grey dots) point is lower (at $50.00) in the case of the long stock position than it is (at $55.50) in the case of the long calls position. This tells us that a trader who purchased the stock, rather than the calls, would be in a profit as long as the stock were trading above $50.00. However, the trader who purchased calls instead of the stock would suffer a loss unless the stock was trading above $55.50 at options expiration.

In the event of a large rally in the underlying stock — let’s say, to 65 — the stock trader would make a bigger absolute profit ($15.00) than would the options trader ($9.50). In this aspect, it might be considered that owning the stock is the better alternative. However, note than on a relative percentage basis it is the options trader (9.50/5.50 = 172%) who would make a much larger profit than would the stock trader (15.00/50.00 = 30%).

A Long Calls position provides the trader with a lot more leverage than does a Long Stock position. This facet — providing a greater bang for the buck in addition to a low cost of entry — is a leading motive for trading options.

Furthermore, the stock trader has to deal with the potential of a substantial loss. After all, a stock can decline all the way to zero, thus causing the stock trader both a larger percentage loss (100%) and a large absolute loss ($50.00). On the other hand, while the option trader can lose his whole investment (100%), he can rest assured that the absolute loss given any adverse move in the underlying stock, will only result in a relatively small absolute loss ($5.50).

Summarizing the discussion of long stock vs. long calls: the optimum choice ultimately depends on the level of confidence that the trader has in his opinion on the underlying stock and the level of security that s/he desires. If the trader is completely certain that a rally will take place, and s/he is later proven to be right, trading the stock is probably the better alternative. If, on the other hand, s/he desires a high level of security, a long calls position might be the better choice, because it provides much more security than does outright ownership of stock.

Time Decay

So far, we’ve looked at the long call strategy from the perspective of its value as on expiration day. However, the option obviously has a life before it expires, and its value changes over its lifetime. The following diagram depicts the payoff of a long calls strategy on a given day prior to expiration.

The illustration above shows two payoff lines relevant to the call option in the example used earlier: one (red line) shows the payoff of the call option at its expiration and the other (dark grey line) shows the payoff as at the time of inception of the trade, which is 6 months before expiration in our example.

The dots on the diagram represent the respective breakeven points as on the day of expiration (grey dot) and on the day of inception (white dot), respectively. In this graph, the breakeven point at the time of trade inception was at the same level as the strike price, because it just so happens that the stock was trading exactly ‘at-the-money’ when the trade was initiated.

As we’ve spoken of in Introduction to Options Pricing , the area in between the interim payoff line and the expiration line represents the time value of the option. The option will always have an element of time value, before it expires.

The possessing of time value means that — before expiration — the option will: a) be trading at a value greater than its intrinsic value, and b) as a result of the previously mentioned fact, the breakeven price (see white dot) will be lower before expiration than it will be at expiration.

Furthermore, the presence of time value means that an option that is trading out-of-the-money (stock price is below strike price) does not show a dollar-for-dollar decline in value when compared with the stock. For example, if the underlying stock in our example declines to $47.50, the loss on the stock position is $2.50, but the loss on the options position is approximately $1.50. If the trader decides to stop out of the options position, he/she can do so with a smaller absolute loss than would have been the case with the stock position. Let’s now see how the passage of time affects the value of an option (before expiration of the option).

Passage of Time. Negative Effect

A Long Call option that has several months to expiration, commands a higher value than does a long call option that has less time to expiration.

Holding everything else constant, the shorter the duration to expiration, the lower the value of a long calls position. What this also means, is that the breakeven point keeps moving higher and higher as time goes by, thus making it harder and harder for the position to move into a profit. The illustration above shows how the call option from our example loses value as it nears expiration.

Volatility Bias

Long call options are inherently long implied volatility. In other words, the level of implied volatility has a direct relationship with the value of the option; the higher the level of implied volatility, the higher the value of the long call option, and vice versa. The topic of volatility is rather complicated and we won’t delve too deeply into it, at this point.

The following diagram helps illustrate how the interim payoff line of a long calls position shifts, given a raising or lowering in the level of implied volatility.

Implied Volatility Increases. Positive Effect

A rise in the level of implied volatility brings about a rise in the value of a call position. Notice how the payoff line in the illustration moves upwards when implied volatility rises from 30% to 40%. This increase in the value of the option, in turn causes a lowering of the breakeven point, and makes it easier for attainment of profitability in the trade.

The larger the rise in implied volatility, the higher the value of the option. In fact, in a few extreme cases, implied volatility can rise by such an extent as to counter the negative effects of time decay and possibly even of a stagnant underlying stock price.

As a result, a trader who is neutral on the price of the underlying stock itself, but is bullish implied volatility — i.e. he expects a massive surge in the level of implied volatility — might occasionally look to utilize a long calls strategy. (However, there are other slightly more advanced options strategies that would work better, in such a circumstance.)

Implied Volatility Decreases. Negative Effect

A decrease in the level of implied volatility brings about a fall in the value of the call option. Notice how the payoff line appears to move to the right when implied volatility falls from the original volatility level (30%) to a lower volatility level (20%). This depicts a decrease in the value of the option, which of course also brings about a raise in the level of the breakeven point and makes it harder for an attainment of profitability in the trade.

The farther implied volatility falls, the lesser the time value of the option and, in turn, the harder to achieve breakeven on the trade.

As a result, great precaution should be taken in purchasing calls that are trading at a high implied volatility, for example, such as that usually seen in the period preceding an earnings announcement. A crash in implied volatility would mean that there would need to be an extremely large rise in the price of the underlying stock in order for breakeven to be achieved.

To summarize, a long calls position usually requires stable to expanding conditions in implied volatility. A severe expansion in implied volatility might counter the negative effects of a stagnant stock price and/or of time decay. However, the corollary to this is that a long call option that has been purchased at a high rate of implied volatility might require an extremely large move in the underlying just to breakeven.

Strategy Variations

The Call buyer does not necessarily always choose the at-the-money strike. He/she might choose a strike that is away-from-the-money, i.e. a strike price that is either above or below the current price of the underlying stock. The decision regarding the strike that is chosen is based on the extent to which the trader wants to utilize leverage and/or curtail the effect of time decay.

Normal Variant. Long At-The-Money Calls

The most typical use of the long calls strategy involves the purchasing of calls on the strike price that is closest to the current price of the underlying stock. This strike price is, of course, known as the at-the-money strike. The following is a payoff diagram of an at-the-money long calls position.

As the illustration shows, in this — the normal — variant of the long calls strategy the current stock price (50.0) and the chosen strike price (50.0) are the same as or very close to each other. (In reality, the stock would typically be trading at a price that is slightly away from the nearest strike). We won’t explore the nuances of this variant much further, since it is the base case and has been spoke of in detail previously.

Aggressively Bullish Variant. Long Out-Of-The-Money Calls

Occasionally, a trader might possess a very strong conviction about expected future price movement (upwards) in the underlying and/or might want to impose a high level of leverage in the trade. Such a trader would find out-of-the-money calls to be a very attractive proposition.

The following diagram highlights the payoff of an out-of-the-money long calls position. Also included for comparison purposes is the payoff (faded line) of the at-the-money calls position that we’d looked at earlier.

Let’s explore how the aggressive variant differs from the normal case.

We can see that the strike price (52.5) is higher than the current price (50.0) of the underlying stock. Intuitively, it can be understood that this means that the trader must be quite confident that the underlying stock will rally before expiration of the option; if the stock does not rally past the strike price (52.5) before or at expiration, the trader runs the chance of losing his entire investment.

The fact that the strike price is higher obviously also means that the breakeven level is higher and, thereby, profitability harder to attain than in the case of the a-t-m call option.

However, even though there is a higher risk of losing the entire investment in this — the aggressive — variant of the long calls strategy, the tradeoff is that the o-t-m option costs less than the a-t-m option does. In other words, the absolute max loss is less than it is with the normal variant of this strategy (assuming of course that the same number of contracts are purchased).

The maximum profit is still unlimited and, given a large rally, the absolute profit will only be marginally less than in the case of the normal variant. The percentage gain, of course, will be larger than in the case of the normal variant.

A couple of other points, which are not apparent in the diagram provided above, but are otherwise significant in the case of out-of-the-money options include the following:

a) Higher sensitivity to changes in Implied Volatility:

An increase (decrease) in the level of implied volatility causes a much larger percentage increase (decrease) in the value of out-of-the-money options than it does in the that of at-the-money options.

b) Large effect of Time Decay:

Out-of-the-money options lose time value at a much faster clip than do at-the-money options.

These two tendencies demand that if the trader wants to close the aggressive long calls position before expiration, not only does he require a large and quick move in the stock but also that implied volatility levels not decline too much in the interim.

Cautiously Bullish Variant. Long In-The-Money Calls

When a trader is not very confident that a stock will rally strongly and perhaps believes that only a marginal rally will ensue, she might opt to buy options that are in-the money (strike price is below the current price of the underlying stock).

A primary reason for the trader to use this variant of the Long Calls strategy is that in doing so he is able to lock-in a maximum loss, in the event of an unexpected downward gap in the stock. Another motivation is the fact that these options trade with very little time value, if any at all (and therefore the lower potential loss given sideways trading action).

Interestingly, a trader who is neutral — expecting sideways movement — on the underlying stock but is expecting a substantial expansion in implied volatility might look at using this variant of the Long Calls strategy (see topic Volatility Bias: If Implied Volatility Increases in this write-up, for further information).

The following diagram highlights the payoff of an in-the-money long calls position. Also included for comparison purposes is the payoff (faded line) of the at-the-money calls position that we’d looked at earlier.

Let’s explore how the cautious variant differs from the normal case.

We can see that the strike price (47.5) is lower than the prevailing price on the underlying stock (50.0). Given this information, we can see that the trader does not require a big move in the stock in order for the option to expire with a reasonable portion of its original value intact.

As we can see from the diagram, the fact that the strike price is lower also means that the breakeven price level is lower than in the case of the normal variant. These benefits are offset, however, by the fact that the options cost more and, therefore, carry a larger potential absolute loss than in the normal case.

The maximum profit is potentially unlimited and, on an absolute basis, a little higher than in the normal case. The percentage gained on investment, given a large rally, however, is less than that of the normal case.

Also, it should be stated that if the trader is interested in closing the position before expiration s/he would be glad to note the following tendencies, which are not apparent in the diagram provided above, of in-the-money options:

a) Lower sensitivity to changes in Implied Volatility:

An increase (decrease) in the level of implied volatility causes a much smaller percentage increase (decrease) in the value of in-the-money options than it does in the case of at-the-money options.

b) Lesser effect of Time Decay:

The effect of time decay on in-the-money options is limited in comparison to that on at-the-money options. This is because i-t-m options have a relatively small amount of time value (although they have a high intrinsic value) to begin with.

These tendencies mean that when using the cautious variant of the long calls strategy, time is on the side of the trader (in relation to when she uses the normal or the aggressive variant).

Follow-Up Action

While the long calls strategy does not have the range of potential corrective follow-up measures that more complex options strategies do, given an unfavorable move in the underlying stock, the strategy is very conducive to protective measures given a favorable move.

We’ll use the following example to illustrate a few of the potential follow-up strategies that the long calls trader has at his/her disposal:

Booking/Protecting Profits

Given an upward move in the stock, the long calls holder can choose from a handful of potential courses of action. These include:

a) Closing the Trade

If the trader does not believe that the stock will rally much further, he might look to close out the position immediately, rather than experience a potential decline in the stock or a loss of time value in the options. Using the example provided above, if Situation A occurs the trader can look at selling his MAR 50.0 Calls for $5.40 — a $1.65 (44%) profit — and move on to the next trade.

b) Trimming the Position

If the holder of a profitable Long Calls position believes that the stock might rally further, but does not want to lose unrealized gains in the event that he/she is wrong in this belief, she could sell off a portion of the existing position. This would lower the average price paid on the Calls, as well as allow for further profitability.

Using the example provided above, if Situation A occurs the trader can sell a portion, say 50%, of her MAR 50.0 Calls, for $5.40 and hold on to the rest. This trade adjustment would lower the average price to $2.10 on the remaining position. Profits can then be booked on the rest of the position given further progress in the stock, or the position can be stopped if the stock starts to turn downwards.

c) Rolling Into a Bull Call Spread

If the trader believes that the stock might rally a little further or stay at current levels as expiration approaches, he might be able to alter the risk-reward picture by rolling the long calls position into a Bull Call Spread. The trader would do so by selling calls at a higher strike price and waiting for time decay to expand the spread as expiration nears.

Using the example provided above, if Situation A occurs the trader can look at holding his position in MAR 50.0 Calls and initiating a short position on an equivalent number of MAR 55.0 Calls, which are now trading at $2.60. The resultant net position would be a MAR 50.0/55.0 Bull Call Spread.

Rolling Long Calls into a Bull Call Spread: The dashed lines signify the original price of the underlying stock ($50.00) and the price ($54.00) at which the adjustment was instigated. The dotted lines signify the two strike prices ($50.00 and $55.00). The blurred and the full dots depict the original breakeven point and the new breakeven point, respectively. The arrows signify the movement of each element, after the trade adjustment.

As the diagram above shows, the net cost of the spread is $1.15. Rolling into the spread brings about a cost reduction — and a decrease in potential max loss — of $2.60. Notice that the shifting of the payoff line has also brought about an improvement in the breakeven level.

However, note that the max profit is not unlimited any longer; it is capped at $3.85 ($55.00-50.00-1.15) and is attained if the underlying stock is trading at $55.00 or above (at options expiration).

d) Rolling Into Other Kinds of Spreads

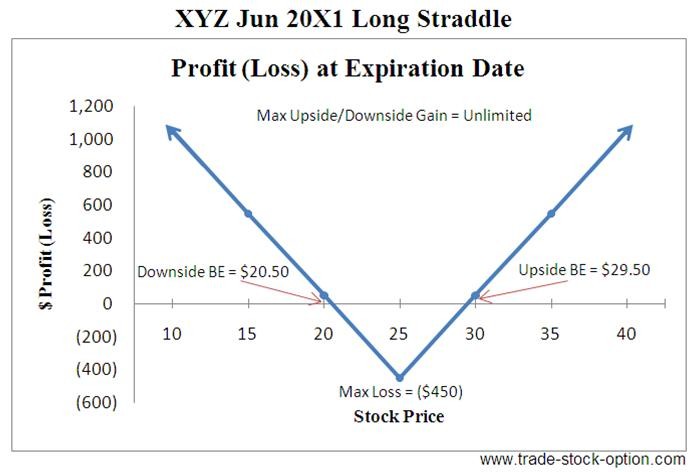

Although it is the most commonly used, the Bull Call Spread is only one of a myriad of spreads that a winning long calls position might be rolled into. Others include: Call Backspread, Call Ratio Spread, Long Christmas Tree, Long Straddle/Strangle and a myriad of Time Spreads. The particular strategy chosen would depend upon the trader’s continuing directional and implied volatility biases.

Repair Strategies :

Given an unfavorable (downward) move in the underlying stock and a situation wherein the trader is not willing to cut losses by closing the trade — perhaps in the belief that there is a reasonable chance for a recovery — there are a couple of quasi-repair strategies that might be applied to a losing long calls position. These include:

a) Averaging Down

If the trader believes her bullish outlook will prove to be right in the end and that the stock is just eking out a bottom, she might think about buying some more calls at their current — lower — price. This will improve the breakeven point and might actually prove to be quite profitable if the stock soon starts to rally.

Using the example provided above, if Situation B were to arise, the trader might look to average down by adding a few more MAR 50.0 Calls (now trading at $1.10) to the original position. Assuming that the trader adds an equivalent number of calls as in the first position, she would lower her average price to (3.75+1.10)/2 = $2.43. This reduction in cost would give her a better opportunity to salvage losses (given an impending rally).

One method of averaging down, called Dollar-Cost Averaging, might also be found to have interesting results when applied to options (because of the non-linear aspect of options pricing). If the trader were to add an equivalent dollar-amount as that used in the first trade — this addition would convert to 3.75/1.10 = 3.4 times the # of contracts used in the original position — and further lower the average price to a more easily attainable $1.70.

b) Adding Calls of a Lower Strike

If the stock has fallen considerably, say as far as one or two strikes below the original strike, and the trader still believes that he will be proven right in the very near future, he might consider purchasing more Calls at one of the lower strikes.

If he is then proven correct, the rebound in the stock will provide him with gains on the second Call position and a recouping of some of the unrealized losses from the original position. Taken together, the net returns from these two positions might bring about a breaking even or a small profit.

One thing that we notice from these two potential courses of action — for a trader who holds a losing long calls position — is that they both involve the purchasing of more options.

Making these trade adjustments, therefore, means that additional risk is brought into the picture. If the trader is proven to have been wrong in his beliefs that the stock will rally immediately, he will not only lose his original investment but possibly also a part or the whole of his additional investment.

To summarize, a long calls position is a great way to leverage one’s bullish opinion on an underlying stock; it provides a given maximum loss and a theoretically unlimited potential profit. Moreover, if the holder of a winning long calls position so wishes, he/she has a myriad of protective measures to choose from in order to lock-in profits. However, a trader who holds a losing long calls position, might find it best to cut losses by closing the position, unless she is willing to take on additional risk in initiating a repair strategy.