Inspecting A Country s Debt

Post on: 2 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Nothing ruins a nice dinner party quite like discussing economics and fiscal policy. Blood boils, friends become enemies and no one bothers touching dessert. In the United States the rancor and gnashing of teeth over such matters reached a fever pitch during the 2012 elections and still carries on through negotiations over the federal budget. Questions about the role of spending and debt are a global issue, but the core issue isn’t how much to spend or what to spend it on as much as it is on whether debt is inherently bad. Tensions over just how to handle debt are pitting the rich world against the developing world like never before.

Developed Does Not Mean Better

Researchers often focus on the debt of developing countries rather than the debt of the rich world. To a certain extent this makes sense considering that developing countries can be neophytes when it comes to managing external debt and the flow of money. Developing country governments are faced with an ever-broadening array of financing options and may find themselves on the verge of a debt crisis, without strong institutions and policies in place to keep debt in check.

The argument posited by international organizations such as the IMF and World Bank, as well as rich world crediting nations, is that developing countries should follow the sort of policies described in the Washington Consensus. The 2008 global crisis has turned the argument on its head, however. According to the IMF, general government gross debt for advanced economies grew from 72.5% of GDP in 2000 to 109.9% in 2012, with much of that increase occurring after 2008. During the same period, emerging markets and developing economies saw their percentage drop from 36.6 to 34.4%.

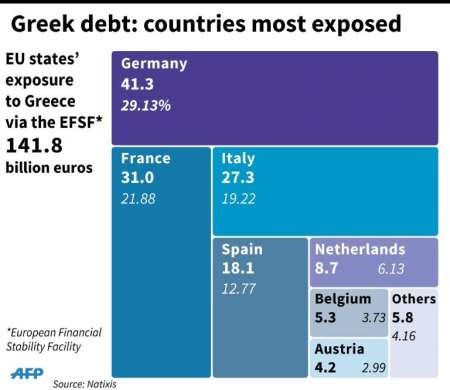

Of the 35 countries considered advanced by the IMF, all but nine are in Europe, which has yet to right itself four years into its sovereign-debt crisis. Between 2008 and 2011, 13 European countries – half of all European countries considered advanced — had increases of general government gross debt exceeding 40%. In short, some developing economies are less indebted than developing ones.

Public Sector Vs. Private Sector Debt

Arguments over debt tend to focus on government debt, with particular focus on government debt as it relates to GDP. While high-debt ratios do indicate a greater claim on future growth by creditors, since debt requires service payments, focusing solely on government debt misses the other elephant in the room: private sector debt.

To illustrate how focusing solely on government debt can turn into a Titanic-meets-iceberg moment, Cyprus, the small island nation now dominating financial news, was flying under the radar with a debt ratio of 61% in 2010 (compare this to 98% in the United States). What everyone missed was that its banking sector debt was nearly nine times its GDP in 2010; the eurozone average was 334% in 2010.

Governments – and ultimately taxpayers – face two issues when it comes to debt. High government debt means that a greater portion of tax revenue has to be earmarked for debt service payments. This reduces funds for other programs. High private sector debt, while ostensibly backed by investors in the companies taking on debt, can wind up pulling in the government. Hence the popularity of the “too big to fail” quote.

In some respects private sector debt is more frightening than public sector debt, since a government keeping a tight fiscal ship won’t have as much of an impact (hence monetary policy). For example, a banking crisis in the private sector can cause business credit to seize, unemployment to spike and bankruptcies to ensue. This in turn would lead to decreased tax revenue, which would lead to a vicious cycle of cuts and contraction.

For many developed nations with sophisticated banking systems, a good portion of private sector credit comes from within. A review of World Bank data on domestic credit to the private sector shows that 23 developed economies had ratios greater than 100% of GDP in 2011, with five countries – Cyprus, Denmark, Ireland, Spain and Hong Kong – with ratios greater than 200%. This matters because a private sector failure, such as a collapse of several big banks, will hit residents harder. This is part of the reason the European Central Bank is at odds with Cyprus. domestic depositors don’t want to take a hit.

How well a country manages its finances is rarely addressed until something goes wrong. In this sense, strong institutions and close vigilance can reduce the possibility of failure, but incentives often align to push governments toward policies that may kick problems down the street, rather than face them in the present. America allowed loose credit leading up to the financial crisis. while Cyprus basked in the warmth of being considered a banking haven. Debt statistics matter, but the complex workings of economics makes them only part of the overall picture.

Investors looking to take advantage of growth opportunities while reducing risk have a tough task ahead of themselves. The interplay of economic indicators is complex, but some general rules of thumb apply. Countries can run deficits, but just like the average Joe must be able to weigh the cost of borrowing with future growth. The higher the ratio of debt to GDP the more likely a country is to get into trouble.

For the optimist, looking into countries with healthier balance sheets will bring more stability, but with reduced risk comes slower growth. For the pessimist, investing against the negative consequences of a country running a greater deficit can mean taking positions that profit from increases in interest rate spreads. Investors can also look to currency trading to take advantage of a possible default.