Ending Tax Breaks On Municipal Bonds Shifts Burden To The Rest Of Us

Post on: 16 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

English: A view from the Member’s Gallery inside the NYSE (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Better check that portfolio: the Obama administration is continuing to push for limits on the tax exemption of municipal bonds. The plan was tucked away in the President’s budget introduced in April but hasn’t attracted much public attention – until now, when it appears that the cap may actually happen.

Traditionally, municipal bonds have attracted investors because the interest income is tax exempt for federal income tax purposes. Depending on the investment, the interest income may also be exempt for state and local income tax purposes. There’s a reason for the exemption: municipal bonds are generally private investments in state and local government projects like schools, hospitals, water projects and roads and the federal government has an interest in encouraging those kinds of investments.

Here’s how it works. Suppose a local government needs money. Typically, it can: (1) cut spending; (2) raise taxes; or (3) borrow money. Since the first two options are often impossible or not palatable, borrowing money is generally the most appealing. But even in the pre-”too big to fail” bank era, banks don’t generally hand over giant checks to cities and towns that might already be struggling to pay bills. Instead, the city or town borrows money from the public with the promise to pay the loan back over time with interest. That loan is called a municipal bond.

The primary appeal of municipal bonds (coupled with other selling points like traditionally lower transaction costs and smaller investment minimums) is the tax exempt piece. The interest has traditionally been exempt from taxation – a tax break that dates more than 100 years. In Pollock v Farmers’ Loan & Trust Company. 157 US 429 (1895), the Supreme Court held that the federal government had no power under the Constitution to tax interest on municipal bonds.

Yes, that was the same case that found the original federal income tax to be unconstitutional.

Congress “fixed” the apportionment problem in Pollock by passing the 16th Amendment. That amendment, codified in the Revenue Act of 1913, also allowed for (but not mandated) the federal exemption of interest earned on state and local bonds.

The exemption on municipal bond interest appeared in court again in South Carolina v Baker. 485 US 505. The case made its way to the Supreme Court after Congress passed a law tying the exemption to a requirement that the bonds be registered (as opposed to merely held by the owner, what you think of as “bearer bonds”). The State of South Carolina sued, claiming that the requirement was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court disagreed, with Justice Brennan writing :

Any federal regulation demands compliance. That a State wishing to engage in certain activity must take administrative and sometimes legislative action to comply with federal standards regulating that activity is a commonplace that presents no constitutional defect.

The Supreme Court also found that Congress could choose to tax interest income on municipal bonds if it wanted to, noting, “the owners of state bonds have no constitutional entitlement not to pay taxes on income they earn from state bonds, and States have no constitutional entitlement to issue bonds paying lower interest rates than other issuers.” Only Congress didn’t tax that interest. The statement, of course, set the stage for potential future challenges to the exemption – and that’s what we have now.

Under the current tax proposal, the tax exemption for interest on municipal bonds would be capped at 28% for those taxpayers at the top. Here’s a quick example of how it would work: let’s assume that someone in the top tax bracket (39.6% for 2013 ) earned $10,000 in municipal bond interest. The federal income tax bill on that interest right now is 0. Under the proposal, the taxpayer would shell out $1,160 in federal income tax: 39.6% of $10,000 is $3,960 less the exempt amount (28% of $10,000).

What if taxpayer earned five times that amount? His tax bill would jump to $5,800. And on and on.

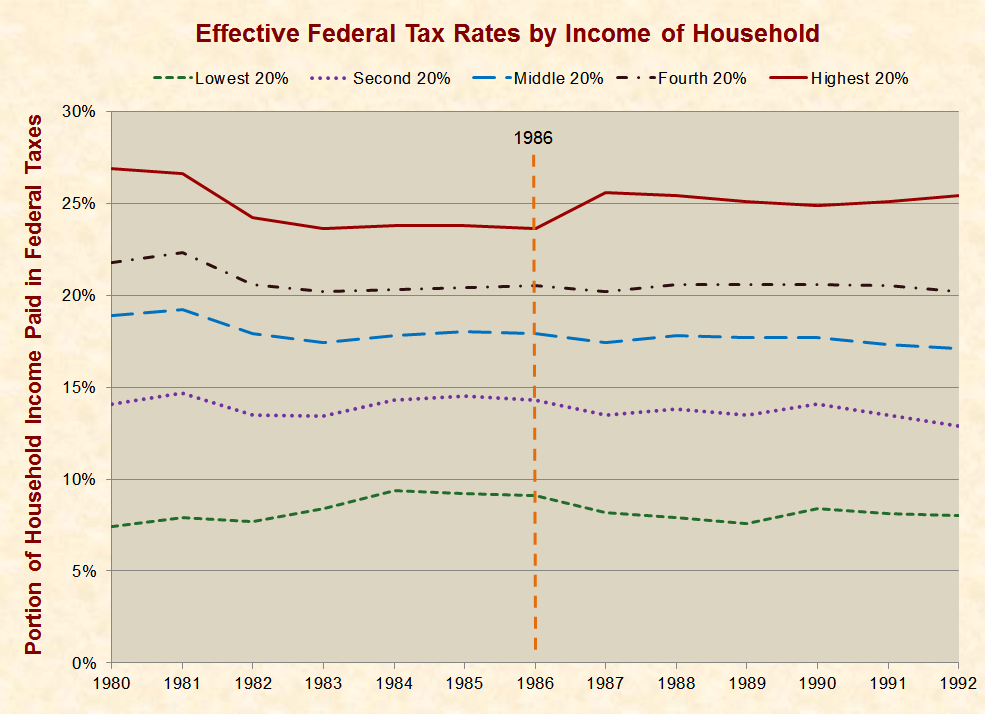

Unlike some other forms of investment, more than 60% of municipal bonds are owned by individuals, often through mutual funds. Most of those individuals are those who pay federal income tax (nothing new there, those in lower income tax brackets tend not to have income producing investments, Mr. Buffett and Mr. Romney excepted). Those in the high tax brackets are attracted to the tax-exempt piece of the bonds as an investment feature. In simple terms, most of those who are going to be affected by this new proposal are high income taxpayers.

And I know what you’re thinking: who cares if the rich have to pay a little more? You should care. And here’s why.

Think back to what I said before about why we have municipal bonds in the first place: it’s to encourage private investment in public projects. Those funds are used to build our roads, improve our schools and fund our emergency responders; schools alone accounted for nearly one-third of state and local infrastructure expenditures financed by private investment over the last ten years. We should want to encourage that investment. If we don’t, go back to beginning of the piece: what are the options now? Cut spending (meaning, realistically, those projects don’t happen) or raise taxes (yes, on the rest of us).

A higher tax bill on municipal bonds means that affected investors – those than can afford to shop around – will necessarily seek out other options. They’ll look to find investments that pay out at a higher rate to make up for the higher bite. The result? Instead of money going to public projects – repairing bridges, fixing dams, funding schools – it will go to Apple Apple. Or Netflix Netflix. Or Coca-Cola Coca-Cola. Or Citi. Is that what we want? There are already plenty of incentives to invest in the private sector; we shouldn’t erase incentives to encourage private investment in the public sector.

As you can expect, mayors, governors, and other local government leaders have voiced strong opposition to the measure. Earlier this year, then Conference of Mayors President Mayor Michael A. Nutter (Philadelphia) joined other national mayors in denouncing the move, saying (downloads as a pdf):

We are extremely disappointed that the budget included a provision that severely limits the tax exemption on municipal bonds that finance the nation’s schools, hospitals, roads, transit, water and other critical infrastructure. The proposal would result in billions of dollars in increased interest annually for communities all across the country… We support the President’s new proposals on infrastructure, but they should not come at the expense of the primary tool for infrastructure financing and job creation.

A 2013 study (downloads as a pdf) prepared for The National League of Cities and the Conference of Mayors estimated that if the cap had been put in place in 2012, it would have reduced economic activity in the nation’s cities by nearly $25 billion. The same study projects losses of 311,000 jobs and $24 billion in GDP as a direct result of the cap.

I know that the tax cap on municipal bond interest feels like an easy bump in revenue. But it’s far from painless. Scaling back an exemption available to taxpayers for more than 100 years won’t just result in collecting more dollars. It will alter incentives for private investors to have a stake in public projects and it will make borrowing for those projects more expensive for state and local government. That isn’t bumping revenue: it’s merely shifting it around. And it affects all of us.