Did Financial Companies Learn From The 2008 Crisis

Post on: 8 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Seven years after the housing bubble peaked and the resulting credit crunch. it’s not hard to make a few general statements about the circumstances that fueled much of the excess. Though the U.S. government has chosen to do little to change how financial companies are structured and managed, this seems like one of the core contributing features of the most recent crisis. It may be time, then, to consider whether the U.S. financial system would benefit from a new model for its financial companies. (For more, see: Getting To Know Business Models . )

Underlying Premises

There were many contributing circumstances to the emergence, growth and collapse of the housing bubble. Like most disasters, the problem wasn’t so much a single factor as a combination of multiple reinforcing factors that ultimately led to trouble. That said, the structure of many financial companies appeared to have played a major role.

A large percentage of the major players in the credit system — banks, investment banks and insurance companies — were all structured as public corporations. While this structure theoretically gives every shareholder a voice in how the company is run, in practice it almost never worked that way. Instead, boards of directors and senior managers acted as they saw fit, particularly when it came to the compensation and risk management philosophies of the company.

Across the spectrum of companies, there was widespread excessive risk-taking, with virtually no accountability or personal risk involved. While an individual trader, banker or portfolio manager could be fired for a series of bad trades, and executives could be fired for hiring too many ineffective employees, the shared risk stretched no further than that job. At the same time, managers were rewarding successful employees with huge cash payouts and little apparent concern for the risk they took to produce the results.

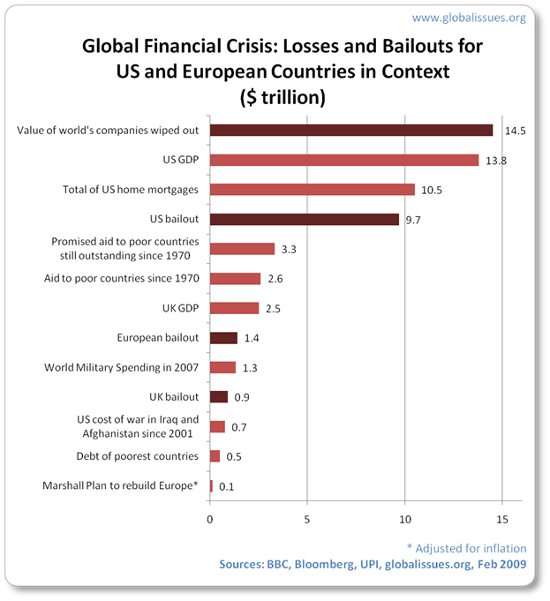

When it all fell apart, numerous financial corporations received millions of dollars from the government to stay afloat, but bonuses already paid out were left untouched. Consequently, the system essentially evolved into a heads, I win; tails, you lose scenario, where executives had everything to gain by taking on outsized risks (large salaries and cash bonuses) and very little to lose if it all went wrong. (Read: CEOs With Risky Lifestyles: Should You Care? )

Are There Alternatives?

Financial companies weren’t always structured this way. For much of the business history of the U.S. banks were privately owned, investment banks (and merchant banks before them) were structured as partnerships. and many insurance companies were mutual organizations.

While these are all different structures, they share a few common features as they pertain to financial companies. For starters, they tend to attract and retain less capital, so managers tended to focus on a relatively smaller number of businesses where they had real expertise and understanding. Likewise, with capital in short supply (and expensive), managers were much more conservative about how that capital was allocated.

These structures all often gave senior executives huge personal financial stakes in the fate of the enterprise they managed. While not all partnerships were structured in a way that made partners individually financially liable for the company, many were. All in all, then, these structures often meant that managers had a deep personal connection to their businesses; failure of the business was often tantamount to personal financial bankruptcy or at least significant loss of wealth. (For more, read: Identifying And Managing Business Risks . )

Definite Downsides

These are not perfect organizational structures, and certainly do feel out of place in a financial sector that is far larger, more dynamic and more global than ever before.

For starters, a higher cost of capital means that fewer worthwhile projects will be funded or pursued, and this is less efficient for the economy as a whole. After all, there has to be a happy medium somewhere between enterprising businesspersons or young couples being unable to get loans on any reasonable terms and widespread NINJA loans (no income, no job/assets).

These structures are also inherently exclusionary and inefficient. Banks, investment banks and insurance companies are legitimate enterprises that many people want to invest in, and avoiding public shareholding altogether again removes options from the market and reduces investment and capital efficiency. What’s more, small, siloed businesses are less efficient and that inefficiency filters through to the economy as more expensive capital and slower-than-necessary growth.

Time for a Hybrid?

Hybrids are still all the rage today in cars, and maybe governments need to consider hybrid models for financial companies. Perhaps it would be possible to structure them as modified limited partnerships where regular investors can participate as shareholders, but managers hold a different sort of stake that entitles them to a different share of profits at the cost of more responsibility and personal liability.

In such a model, then, senior managers would essentially be forced to own this different class of shares as a prerequisite of the position. With more of their own assets on the line, perhaps they would be less eager to pursue risk blindly.

Then again, it may be that such advanced measures are excessive. Perhaps there’s a simpler way that fits within the existing structures. What if senior executives were required to hold a certain percentage of their personal financial assets in company shares and could only receive a limited amount of cash compensation in a given year (with the rest in the form of restricted or preferred shares). Such a model would, at a minimum, delay some of the gratification of excessive risk-taking and would enable boards of directors to claw back compensation or otherwise punish those whose decisions ultimately did serious harm to the corporation and its shareholders. (For more, read: $1 CEOs And What They Make Now . )

The Bottom Line

There is no perfect corporate structure, and probably no failsafe method of restraining greed or self-interest. That said, reducing the short-term cash benefits of risky behavior and putting more of a decision-maker’s net worth on the line, might serve as a reasonable brake on destructive impulses.