CRB Trader Archive

Post on: 10 Август, 2015 No Comment

— 2000: Volume 9, No. 6

Swing Trading and Underlying Principles of Technical Analysis

By Linda Bradford Raschke

Traditionally, there have been two major methods of forecasting market movementsthe fundamental method and the technical method. Fundamental factors include analyzing long-term business cycles and identifying extremes in security prices and public sentiment. An investor looking to establish a line of securities after a long-term business cycle low is said to be playing for the long swing. Short-swing trading (also referred to as swing trading) seeks to capitalize on the short and intermediate waves or price fluctuations that occur inside the longer major trends.

The market’s short-term swings are caused by temporary imbalances in supply and demand. This causes the price action to move in waves. A combination of up waves and down waves forms a trend. Once you understand the technical aspects of these imbalances in supply and demand you can apply the principles of swing trading to any time frame in any market.

Swing charts have been used for the past one hundred years as a way to analyze the overall market’s price structure, follow a market’s trend, and monitor changes in the trend. Swing trading has come to refer to trading on the smaller fluctuations within a longer-term trend, but historically, swing charts were used to stay with a trade and follow the market’s trend, as opposed to scalping for quick in and out profits. Whether analyzing the market’s swings for short-term trade opportunities or monitoring them for trade management purposes, it is important to understand the enduring principles of price behavior that forecast the most probable outcome for a market. All these principles are deeply entrenched in the foundation of classical technical analysis.

Swing trading is based on the technical study of price behavior, including the price’s strength or weakness relative to the individual market’s technical position. In other words, the length and amplitude of the current swing is compared to those of the prior swings to assess whether the market is showing signs of weakness or signs of strength. A trader attempts to forecast only the next most immediate swing in terms of the probabilities of reasonable risk/reward ratios for the next leg up or down. A swing trading strategy should show more winners than losers. Swing traders make frequent trades but spend limited time in those trades. Short-term swing trading involves more work in exchange for more control and less risk.

Swing trading is a way of approaching market analysis and risk management that is derived from the basic tenets of technical analysis. It is also a very practical and clear-cut method of trading based strictly on odds and percentages. A trade is based on the market’s most probable immediate course of action as opposed to a long-term fundamental valuation.

The majority of short-term high probability swing trading patterns that have consistently held up over time are based on one of four enduring principles of price behavior. Each of these principles can be quantified. Almost all mechanical systems are based on one of them. Although these concepts can be tested and are considered to be durable and robust, swing trading in the traditional sense should still be considered a method rather than a system.

Principle 1: A Trend Is More Likely to Continue Than Reverse

This principle is one of the basic tenets of Dow Theory: A trend has a higher probability of continuation than it does of reversal. An up trend is defined as both a higher high and a higher low, and vice versa for a downtrend. If the market is in a well-defined trend, the highest probability trades will occur in the direction of the trend. When the price is moving in a clearly defined trend, there are numerous strategies for entry based on the small retracements that occur along the way. These reactions allow the trader to find a tight risk point while still playing for a new leg in the direction of the trend. A test of the most recent swing high or low is the initial objective level, but ideally the market will make a new leg up (or down).

A swing trader should be aware of certain characteristics of trends. The absence of any clearly defined swing or price pattern implies a continuation of the trend. (This can include a sideways trend, too.) In a steady uptrend, the price action can creep upward in a steady, methodical manner characteristic of low volatility. A slow oozing action or steady price deterioration can characterize a downtrend. This type of environment can be frustrating for a swing trader, as there tend to be fewer reactions to enter, but it is important to keep in mind that once a trend is established, it takes considerable power and time to turn it. Never try to make a counter-trend trade in a slowly creeping market.

Principle 2: Momentum Precedes Price

If momentum makes a new high or low, the price high or low is still likely yet to come. Momentum is one of the few leading indicators. Elliott used the term impulse to refer to an increase in the market’s momentum. Impulse occurs in the direction of the trend, so a swing trader should look to enter in the direction of the market’s initial impulse. New momentum highs can be made both in a trending environment and on a breakout of a trading range environment. Finally, new momentum highs or lows can also indicate a trend reversal or beginning of a corrective swing up when they follow a buying or selling climax (creating a V spike reversal). As seen in Figure 1, buying and selling climaxes mark the extremes. The first sharp swing in the opposite direction at point A sets up an opportunity to initiate a trade from the long side at point B. The market rallies to a perfect retest of the previous swing high before consolidating further.

Figure 1:

A trader should look to establish new positions in the market on the first reaction following a new momentum high or low. Any of the retracement methodologies detailed in the second half of this chapter can be used. The only exception to this rule is that a trader needs to be aware of when the market makes a buying or selling climax. This is not a new momentum high or low, but an exhaustion point that creates a vacuum in the opposite direction.

Figure 2 shows a moving average oscillator that made new highs at point A. Momentum precedes price. Point A was the first time the length of the upswing exceeded the length of the last down leg. Note the steady trend of higher highs that followed.

Figure 2:

Principle 3: Trends End in a Climax

A trend will continue until it reaches a buying or selling climax. This tends to be marked by an increase in volatility and volume. There must be a marked increase in the range that exceeds the previous bars. A buying or selling climax indicates that the last buyer or seller has been satisfied. The market then usually begins a process of backing and filling, testing and retracing. As noted previously, Wyckoff detailed the common sequence of backing and testing that the market makes as the volatility creates good tradable swings. Crowd emotions are high, as few are comfortable with the new price level.

Trading on the crosscurrents after a move has exhausted itself sets up an excellent swing-trading environment as setups occur on both the long and the short side of a market. As a broad trading range begins to form, whipsaws and spikes or springs and upthrusts create support and resistance levels. It is a short-term swing trader’s job to note these areas of resistance and support, as it is at these points where risk can be minimized. Once support and resistance are defined, the market’s range will tend to contract as it begins its drawn-out process of consolidating toward an equilibrium point again.

A market that makes an extremely sharp reversal, following a buying or selling climax, has made a V spike reversal, one of the most powerful technical patterns. Essentially, a vacuum is created in the opposite direction, and the market’s impulse sharply reverses direction without the normal consolidation period.

Figure 3 illustrates an example of Principle 3. This buying climax left a vacuum to the down side. The downside impulse led to the formation of a bear flag. Do not look to buy retracements after a buying climax.

Figure 3:

Principle 4: The Market Alternates between Range Expansion and Range Contraction

Price action tends to alternate between two different states. The range is either contracting in a consolidation mode, or it is expanding in a breakout or trending mode. When the range is contracting, the market is reaching an equilibrium level. At this point, it becomes very difficult to read the market swings. The only thing you can predict is that a breakout is increasingly likely. Once a market breaks out from an equilibrium point, there are high odds of continuation in the direction of the initial breakout. It is easier to predict a pending increase in volatility than it is to predict the actual price direction of a breakout. A trader should think of a breakout strategy as another form of swing trading, as the objective is to capture the next most immediate leg with a good risk/reward ratio.

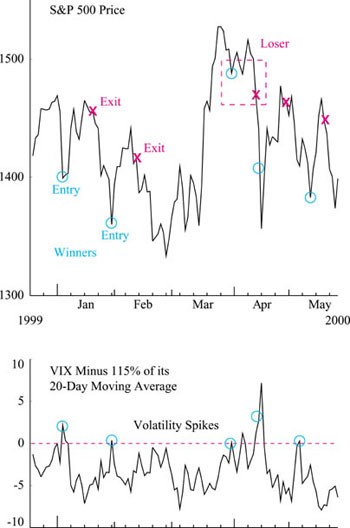

Figure 4 illustrates how the market alternates between range contraction and range expansion. Note how the circled periods of consolidation are followed by a jump in volatility at the points marked with an X. Also note how cyclical this phenomenon is.

Figure 4:

Creating Swing Charts

Swing charts are a trader’s road map by which to anticipate the next most probable play. They are similar to point and figure charts in that they eliminate the time axis and can represent a lot of price action in a relatively small amount of space. Thus, it is easy to see multiple support and resistance levels from past price action. A new swing is drawn in only when the last one is completed, so in one sense they might appear to be one step behind. However, they are the best tool for quickly assessing the overall market’s trend and highlighting the small reactions that occur in a trend. Although most software charting packages do not have a swing-charting format, it takes very little time and work to keep them by hand. In fact, a well-trained eye will be able to see the market swings by studying a simple bar chart.

There are several ways to create or calculate swing charts. The easiest way is to mark the significant swing highs and lows, in other words, a high that is surrounded on both sides by a lower high. The first decision to make is what level of detail to include. There are many smaller swings within swings, and the sensitivity of the chart can be adjusted to include the minor swings or only the greater picture. Gann kept two swing charts concurrently. The first recorded reverse moves or reactions that lasted two to three days. A bar that reached a low that was surrounded on either side by a higher low marked the bottom of a downswing, and vice versa for an upswing. He also kept a swing chart of a longer time frame that marked the highs and lows on a weekly chart. Thus, he was always able to see the short swings within the context of a larger trend.

A trader can adjust the threshold for the swings by changing the number of bars and requiring higher lows to follow a key swing low. If the rule states that an upswing will begin only after four higher lows have followed a key swing low, there will be fewer swings but less noise than if a trader uses Gann’s method of looking at just two- to three-day lows. Of course, Gann kept longer-term charts too, and as a trader will quickly see, there is no right or wrong parameter for creating swing charts. It all depends on one’s personal time horizons for making a trade.

A second way to create a swing chart is to add a percentage function to the most recent swing low (or subtract it from the most recent swing high). If the market trades above this level, a new wave has started in the opposite direction. In his book Filtered Waves (Analysis Publishing, 1977), Arthur Merrill, one of the great market technicians, used a 5 percent swing function to analyze the swing structure of bull and bear markets.

The third way to create swing charts uses volatility functions popularized by the influential technical analyst Welles Wilder in his book, New Concepts in Technical Trading Systems (Greensboro, NC: Trend Research, 1978). A True Range function is added to the most recent swing low or subtracted from the most recent swing high to signal a new wave in the opposite direction. True Range is defined as either the distance between today’s high and today’s low or the distance between today’s extreme price and the previous day’s close, whichever is greater. It is best to use a moving average of the True Range to smooth this variable out. The look-back period for the moving average can be one of personal preference. Also, it is best to multiply the moving average of the True Range by a factor of two to three, or else the swings will be too sensitive and include far too much noise to be of value.

Let’s assume the market is making new lows in a downtrend. When the price can rally above two times a ten-period moving average of the True Range, an up wave will begin. When the price closes below this most recent swing high, less a factor of two times a ten-period moving average of the True Range, a down wave will begin. Again, the length of the moving average used and the multiplier factor can be a range of variables. There is no right or wrong parameter!

Thus, the swing trader is able to quantify a wave through one of three different methods. An uptrend is established when two up waves make higher highs and higher lows. The swing trader then looks to enter on all retracements in the uptrend until a new downtrend is signaled by two down waves with lower lows.

This sounds simple enough. But traders really gain an edge when they learn to use two time frames at once, just as Gann did. The longer time frame is used to identify the trend, and the lower time frame is used to look for short-term reversals in the direction of the trend. If the weekly chart is in an uptrend, wait for a down wave on the daily charts to reverse itself and use this as a long entry.

As mentioned previously, short-term swing analysis is a lot more work and involves a larger time commitment than investing for the long swing. The importance of routine and mechanics can be critical to a trader’s success. Most successful swing traders find it useful to maintain and study charts on a daily basis. Although this process may seem laborious, it keeps the trader actively involved with the markets.

Editor’s Note: The preceeding article is an excerpt from a chapter by Linda Bradford Raschke in New Thinking in Technical Analysis: Trading Models From the Masters. edited by Rick Bensignor, ©2000 by Bloomberg Press. Published by arrangement with Bloomberg Press. Available wherever books are sold or by calling toll-free 1-800-252-1102.

Linda Bradford Raschke , the president of LBRGroup, began her career trading equity options as a member of the Pacific Coast Stock Exchange. In 1984, she became a member of the Philadelphia Stock Exchange, where she continued to be a self-employed trader of equities, options, and futures. In the early 1990s, she started LBRGroup and later became a registered Commodity Trading Advisor. Currently the director and principal trader for the Watermark Fund Ltd. she manages a commercial hedging program in the metals markets. She was featured in Jack Schwager’s New Market Wizards, and also in Sue Herera’s Women of the Street: Making it on Wall StreetThe World’s Toughest Business. Ms. Bradford Raschke also runs an online education trading site where she shows trades real time made for her own account and provides market commentary. A sought-after speaker at investment conferences across the nation, she serves on the Board of Directors of the Market Technician’s Association and is a coauthor of Street SmartsHigh Probability Short Term Trading Strategies.

To purchase your copy of New Thinking in Technical Analysis: Trading Models From the Masters, click here.

CRB TRADER is published bi-monthly by Commodity Research Bureau, 209 West Jackson Boulevard, 2nd Floor, Chicago, IL 60606. Copyright 1934 — 2002 CRB. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any manner, without consent is prohibited. CRB believes the information contained in articles appearing in CRB TRADER is reliable and every effort is made to assure accuracy. Publisher disclaims responsibility for facts and opinions contained herein.