Corporate agility Six ways to make volatility your friend

Post on: 16 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

You know your market is changing when customers are buying things they shouldn’t be. That was the case in 2009, when managers at a leading US retailer began to notice a steady rise in sales of travel-size shampoos, soaps and similar consumables.

Their prompt analysis pointed to something much bigger than a rush on tiny tubes of toothpaste. It revealed a nationwide trend that was barely visible to other retailers at the time: Consumers, hit hard by the global downturn and often living paycheck to paycheck, were buying the cheapest unit sizes they could find. The trend had first surfaced in the company’s urban locations and quickly moved to the suburbs as the economic crisis spread.

The company’s response was just as nimble as its early detection of the trend. It piloted big changes to its assortments, expanding shelf space for intermediate sizes, running sales on two- and four-packs of goods (not just the 12- and 24-packs) and tailoring its mix and merchandising approaches to the wallets of cash-strapped shoppers. Positive results told executives all they needed to know to rapidly roll out the program nationwide.

The move was a resounding success. The retailer gained market share in key demographic segments, boosting its attach rate (the value of complementary goods sold for each primary product sold) and establishing a reputation for offering good deals. It saw double-digit sales increases—levels unheard of in retail—in the non-discretionary categories it had targeted. What’s more, the company has continued to benefit from many of the analytical techniques it pioneered at that time.

___________________________________________

In this podcast, the author highlights how leading companies look beyond managing the risks of volatility to identify the opportunities, and develop the capabilities—or agility—to seize those opportunities. Media Help

___________________________________________

Here was a dramatic demonstration of agility in action: a large, long-established corporation that was quick to sense and then analyze important market changes, and then just as quick to act. But the company’s actions are the exception rather than the rule. For many businesses in many industries, the concept of agility has proved elusive indeed, particularly in the implementation.

Restraining Gulliver

It has never been easy for large, complex organizations to be nimble. Nearly half of the 674 executives surveyed globally in a 2010 Accenture study have little confidence in their companies’ ability to mobilize quickly to capitalize on market shifts or to serve new customers. Half do not believe that their culture is adaptive enough to respond positively to change. And 44 percent aren’t certain that their workforces are prepared to adapt to and manage change through periods of economic uncertainty.

Results from a survey by the Economist Intelligence Unit echo these findings. More than a quarter of the EIU’s poll respondents said their organizations were at a disadvantage because they weren’t agile enough to anticipate fundamental marketplace shifts.

Even at very senior levels, decisions can take forever—and are often second-guessed. “We thought the big decision had been made months before,” recalls one executive we interviewed. “But apparently, when we had to act on it, it was still being debated. We were furious.”

It’s time for those organizations—and many like them—to try again. From the swiftest startups to the slowest-moving government agencies, every organization needs to move the “agility needle” to the right.

It’s no secret why organizations struggle mightily to do so: Gulliver-like, they are bound by a thousand tiny threads of hierarchy—compartmentalization, interdepartmental conflict, risk aversion and miscommunication, to name just a few constraints. They also tend to view volatility as a limitation rather than an opportunity. At best, they gauge agility by how fast they follow moves made by their competitors.

What’s new?

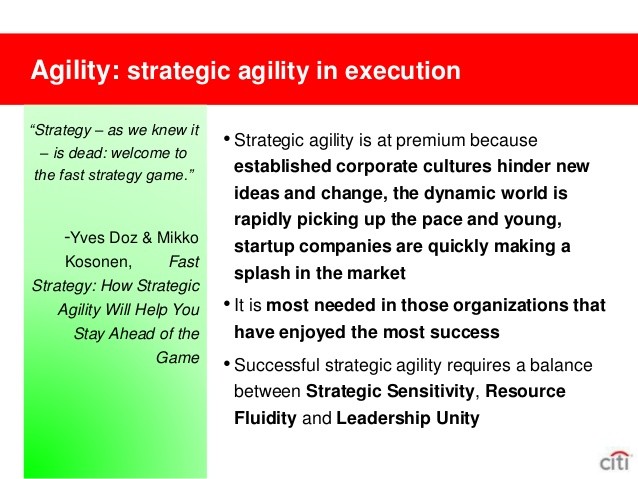

Plenty has been written about the virtues of agility. In 2007, Wharton published Fast Strategy: How Strategic Agility Will Keep You Ahead Of The Game . In the 1980s, Harvard Business Review explored the topic, notably with its landmark article on time-based competition. And decades ago, then General Electric chief Jack Welch was famously preaching about speed and responsiveness.

However, much has changed—and continues to change—to force companies to institutionalize their approaches to agility. And much has happened to enable them to do so: Witness the rapid advances in analytical software. Yet when it comes to exactly how to become agile, pragmatic advice is harder to find.

The good news is that many more executives are now ready to accept change. Gone—or at least going—is the reflexive urge to stick to tried-and-true ways of doing things or the sense of helplessness that market turbulence has so often engendered. Here’s how the chief financial officer of a global hospitality provider describes the new mood: “We had to decide whether we were going to avoid the market uncertainty with a hunker-down mindset or seize it as an opportunity. I think muddling in between is the most risky. With the right mindset, this is a fantastic time to be in business.”

What previously were viewed as once-in-a-lifetime events have become permanent features of the business landscape. As one utilities executive recently told us, “This industry is not supposed to be rocked by changes in technology—and then shale gas emerged.”

Most business leaders can reel off myriad examples of volatility from their own recent experiences. But what is less obvious is the rate of increase of uncertainty.

In the past decade, the US stock market has been much more volatile than in previous periods. Global commodity price swings have been vertiginous. And the list of Fortune 1,000 companies is turning over faster. In their 2006 book Built to Change . organizational effectiveness experts Edward Lawler and Christopher Worley found that between 1973 and 1983, an average of 35 percent of the top 20 companies on the Fortune 1,000 were new to the list. The number rose to 45 percent in the next decade, then soared to 60 percent the decade after that. And it’s likely to top 70 percent in the decade that ends in 2013.

Yet few companies are agile enough to successfully cope with the economic turmoil around them. Some, perhaps, lack consensus among top managers about exactly what agility means (see Sidebar 2 ). But we believe that the real problem is less one of comprehension than of the far more serious lack of readiness and capacity to act. In fact, in many cases, companies have actually become less agile during the recession.

The headlines are filled with names of traditional companies that have failed to adapt to market volatility—companies where the opinions of change-ready managers were quashed. In such situations, it’s often about turf—the fears of some executives that they will lose power or influence or both if they don’t resist disruptive innovation.

In other cases, organizations, in their bids to become hyperefficient, have actually become sclerotic. Consider the legions that reflexively cut headcount when their current quarters’ fortunes sag—spreading the pain over each department without properly weighing the value of the skills lost. Or look at the many companies that have trimmed their supply chains to the bone, reducing their agility, sometimes to the point of embarrassment.

A nonstop opportunity

In his latest letter to shareholders, GE chairman and CEO Jeffrey Immelt nicely summed up his team’s perspective on the need for agility: “When the environment is continuously unstable, it is no longer volatile. Rather, we have entered a new economic era. Nothing is certain except for the need to have strong risk management, a lot of cash, the willingness to invest even when the future is unclear, and great people.”

To be sure, the rise of volatility and market turbulence merits far more attention to getting risk management right. But there is—or should be—more to it than that. Accenture has found that several high performers view ongoing uncertainty as non-stop opportunity.

That doesn’t mean that all high-performance businesses view uncertainty in the same rosy light. The levels of urgency and the potential for opportunity felt by a maker of hard disk drives or mobile-phone handsets are very different from those experienced by a producer of forestry products. But there are consistent themes that come up time and again in conversations with business leaders worldwide.

Our experience reveals six lenses through which these exemplars view volatility in “glass-half-full” terms. This list of lenses is not comprehensive. Nor are the lenses themselves mutually exclusive; there are many ways they overlap with and reinforce one another. Taken together, though, they point to actions that business leaders can take sooner rather than later. Here are quick glimpses through those lenses; each lens is explored in more detail in the following pages

Strategy

It’s time to welcome back scenario planning—this time as an agility lever. Once seen as a rather academic tool used by the C-suite to set a course in industries that run on long economic cycles, it’s now becoming a regular white-boarding approach used by managers at many levels to pinpoint the handful of best options for responding to new situations.

High performers are reviving the discipline not only to mitigate risks but to quickly sound out opportunities that may not be opportunities for long. These companies are investing more so they can deeply understand their industries’ drivers, the new technologies available to them, and the economic and market factors that could disrupt their industry networks.

Explore the Strategy lens in more detail.

Leadership

Companies that can thoughtfully respond to new opportunities and make rapid decisions in uncertain environments share one common trait: Their top managers make decisions quickly and those decisions stick—no second-guessing.

The companies achieve this by investing over the long term to align their top management teams with their markets, their positions within those markets, the strategic levers they can pull and their readiness to pull them. This ongoing exercise in organizational alignment—typically reviewed regularly with the board—involves much more than risk management or crisis management. It means working through a wide array of probable scenarios and gauging how well the top team can deal with the most likely of them.

Explore the Leadership lens in more detail.

Organization

The best performers have realized that they can no longer count on short-term sacrifices and superhuman efforts from all-too-human workers. So they hit “transformation fatigue” head-on by increasing organizational alignment, doing more to bolster the caliber of their workforces and emphasizing collaboration. Their success is gauged by how easily they can overcome organizational inertia and how smoothly and quickly they can make good decisions.

High performers work hard to bolster their entire talent roster—not just their leadership ranks. They do far more than average companies to map their current and future talent lineups against their business needs, seeking many of the traits they look for in their leadership teams. And they craft incentives and compensation plans that recognize and reward those traits.

Explore the Organization lens in more detail.

Marketing

Top performers like the US retailer discussed earlier have more finely tuned antennae than their average peers. They can predict, sense, respond and adapt at speed—in much shorter cycles and in more dimensions than ever before. They use real-time market data and advanced analytics to spot unexpected and incipient shifts in customer behavior, sense competitor moves and predict likely trends. “We look for anomalies in the data—what products are growing fast that shouldn’t, which campaigns are not working that should,” explains an executive at a leading retailer. “Those nuances tell us something. We just have to be smart enough to listen very carefully.”

Explore the Marketing lens in more detail.

Operations

Last year’s earthquake in Japan highlighted the constraints and vulnerability within many companies’ supply chains. In the quest for lower costs, companies have stretched supply chains globally and made them more efficient. However, many now question whether they have gone too far, and ask how they could restore flexibility, transparency and redundancy—without loading up on inventory.

Agile companies have developed dynamic supply chains and operational support systems. They build deeper, more transparent supplier relationships—effectively extending the enterprise beyond the traditional boundaries and ensuring greater visibility and tighter management of the supply pipeline and the demand cycle.

Explore the Operations lens in more detail.

Finance

Large cash balances clearly open up options. But they are only one agility lever. The most agile companies, regardless of size, have also adapted the role and activities of their finance functions. In addition to improving the risk management capabilities, the finance executives at those organizations are changing their budgeting and planning processes to provide greater insight and flexibility. Many are accelerating their budget planning cycles and deemphasizing annual plans in favor of rolling year-on-year or year-plus budgets. Finance’s proactive efforts to manage inventory, credit terms, payments and cash are vital not only for mitigating risk but for capturing upside opportunities.

Explore the Finance lens in more detail.

___________________________________________

These lenses do not constitute an exhaustive list of all it takes to be truly agile. For example, they don’t include information systems—particularly the analytics tools—that will be necessary to support agility efforts. Nor is this brief overview meant to be anything but that. In the pages that follow, we explore each of these lenses in more detail. Our intent here is to spark fresh discussion about what it takes to achieve “institutional agility.”

We also want to encourage leaders of large, complex organizations to view agility as well within their grasp. As one bullish executive told us, “It’s only volatility if you don’t understand it or don’t know how to respond.

For further reading

“ Examining the Euro: Why Does It Matter?”

The New Realities of ‘Dating’ in the Digital Age: Are Your Customers Really Cheating, Or Are You Just Not Paying Enough Attention?

Sidebar 1 | Business agility defined

Few business topics are softer than agility. It’s one of those concepts that everyone thinks they grasp. But it’s a different story when it comes to deconstructing the concept and coming up with practical ways to put it into action.

To anchor our understanding of agility, we should start with the dictionary. According to Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. the definitions are: 1. The ability of being quick and well-coordinated in movement; nimble. Active, lively. 2. Marked by an ability to think quickly; mentally acute or aware.

Here are the components of agility that matter most in a business context.

Anticipating. This means developing a view of possible or likely changes—not trying to predict actual changes. Anticipating includes a rigorous review of customer needs and industry forces, and an evaluation of likely scenarios of industry consolidation, product development, pricing and customer needs.

Sensing. This involves continual reviews of market conditions, looking for trends and especially anomalies in customer behavior, competitor moves, supply chain shifts, supply/demand changes, and macro- and microeconomic developments. It requires strong analytics capabilities.

Responding. The key is to respond to market shifts faster than competitors do. This includes rapid decision making, testing responses on a pilot basis and then scaling for a broader response. It frequently includes preset “plays,” where management teams have agreed ahead of time how they will respond to certain situations—for instance, to a price drop by a competitor or the merger of two rivals.

Adapting. Once initial market changes have been identified, organizations often find that they need to rework some of their business processes. Some may tailor their organizational structures to better handle ongoing changes in their markets.

Sidebar 2 | Questions and answers about agility

Q: How is agility related to volatility?

Agility refers to a company’s capacity to anticipate, sense and respond to volatility in its markets to its advantage. Market volatility is a tremendous source of opportunity for companies that have developed the capabilities to not only manage risk but also respond to it more effectively than their competitors.

Q: I hear lots of terms being used interchangeably. What are the differences between agility, adaptability, versatility, flexibility and resilience?

Each term touches on a company’s ability to respond successfully to change. Agility encompasses the broadest range of abilities. Adaptability applies to organizations that are agile over long periods and can switch to radically new market paradigms, as Fujifilm Corp. has done repeatedly. Versatility typically describes companies such as Amazon.com that embrace a wide range of business models. Flexibility is used for companies that can easily change their supply chains and use multiple customer channels. Resilience refers to a company’s ability to absorb and bounce back after strategic, financial or operational shocks, as Cisco did after the 2000–2001 tech downturn.

Q: Is agile really just another term for innovative ?

Innovation is certainly one element of agility. Agile companies are better at sensing new market needs and quickly developing products or services to meet those needs. To innovate to their fullest potential, they draw on broad and deep strategic, financial, organizational and operational capabilities.

Q: How do we avoid losing control as we strive to become more agile?

Increasing agility does not mean having less control; in fact, many companies find that standardizing processes and defining exceptions increases agility and control at the same time. Agile companies tend to run more experiments and tests, many of which are not market successes. Such tests and experiments should not be ad hoc; they need to take place in a controlled environment.

Q: What is IT’s impact on agility?

IT systems are essential to helping organizations turn volatility to their advantage. They must be able to quickly gather market and operational data internally and externally and analyze the information in real time. Internal reporting systems need to be flexible and provide historical, real-time and predictive performance indicators. IT systems must support greater collaboration and visibility across functions, business units and geographies.

Q: Does risk management inhibit agility?

Corporations need a robust risk management capability to fulfill their obligations to shareholders, customers and employees. Leveraged appropriately, risk management not only identifies vulnerable areas where an organization must protect itself but also identifies areas where a company can create opportunity and take appropriate amounts of risk. (Back to story .)

Sidebar 3 | Twelve-point agility checklist

- Does your organization have at least three scenarios for how your industry is most likely to evolve over the next 36 months? Does it have good options for responding?

About the authors

Walt Shill is a senior managing director with Accenture Management Consulting. He is based in Washington, D.C.

John F. Engel is a Chicago-based managing director with Accenture Management Consulting.

David Mann is a managing director with Accenture Management Consulting. He is based in London.

The authors would like to thank Meg VanWinkle. who leads Accenture Management Consulting Offering Development Thought Leadership, and Rakhee Sheth. a manager in Accenture Strategy, for their contributions to this article.