Adjusting your Collar Trade by Greg Jensen

Post on: 12 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

The Collar Trade is an options strategy that offers low-cost downside protection, but you must give up some potential upside profit. Placing the trade’s options in different expiration months may improve returns.

The market’s recent slide rattled traders, especially those who wanted to join the party and bought stocks just before the downturn in late July and early August. Stocks recovered and began hitting new highs again in late September, but some traders fear the market is due for another pullback.

Cautious traders stay away from high-flying stocks such as Research in Motion (RIMM), Baidu.com (BIDU), Apple Inc. (AAPL), and Garmin LTD (GRMN), but then miss opportunities as those symbols continue higher. How can you possibly have the nerve to enter the market these days? The answer lies in an options strategy “collar trade,” which protects underlying positions against downside losses. If you own or have just bought stock, you can create a standard collar by buying a put and selling a call to offset the put’s cost. A collar is a conservative low-risk, low-return strategy,because the long put caps risk below its strike price, and the short call reduces any potential upside gains above its strike price.

If both options expire in the same month, a collar trade can minimize risk, allowing you to hold volatile stocks. However, a standard collar also restricts the trade’s potential profit to 6-8 percent, which leaves money on the table during bullish trends.

The following example shows how to modify a collar trade to boost potential profits by selling a call that expires 60- 90 days after the long put. This tactic leaves the underlying position briefly uncovered, but the approach works well if you pick fundamentally strong stocks.

Collar Trade Example

Let’s assume you buy 100 shares of stock at $50 on Oct. 15. To create a standard collar, you could first buy a put that expires in 60-90 days with a strike that is at-the-money (ATM) or slightly out-of-the-money (OTM). The last step is to sell a OTM call in the same month. For example, if you bought a January 47.5 put for $2.50 and sold a January 52.5 call for $2.60, the spread offers a credit of $0.10, because you collected more by selling the call than the put cost.

Table 1 lists the collar trade details, and Figure 1 shows its potential gains and losses at Jan. 19 expiration. If the stock drops below $47.50, losses are capped at $2.40 (4.8 percent), but if the stock advances above $52.50, gains are restricted to $2.60 (5.2 percent). The long put gives you the right to sell stock at $47.50, regardless of how far it falls. But the short call obligates you to sell stock at $52.50 — even if it doubles in price by expiration.

This collar trade has a return-to-risk ratio of only 1.08, which isn’t very attractive. However, you can increase a standard collars potential gains by selling a call in a later expiring month.

Twisting the Collar Trade

One way to adjust a collar is to sell the call 60-90 days further out in time than the long put, which lets someone else pay for your downside insurance. This unique approach protects the trade as much as a standard collar trade, but it also lets you take part in bullish underlying moves and offers potential returns of 25-30 percent — roughly four times as large as a standard collar (6-8 percent).

When you sell the call for a revised collar, try to: 1) collect enough premium to pay for the long put, and 2) ensure its strike price is above the underlying stock’s price. If the short call is assigned, forcing you to sell stock at the strike, you want to sell the shares to the call’s holder at a profit.

But after the long put expires, won’t the remaining covered call position (long stock, short OTM call) lack downside protection? At this point, you still must wait for the short call to either move into the money or be assigned. Before answering that question, let’s discuss a couple of key characteristics of stocks that work best in this type of trade. Focusing on fundamentally solid,volatile stocks.

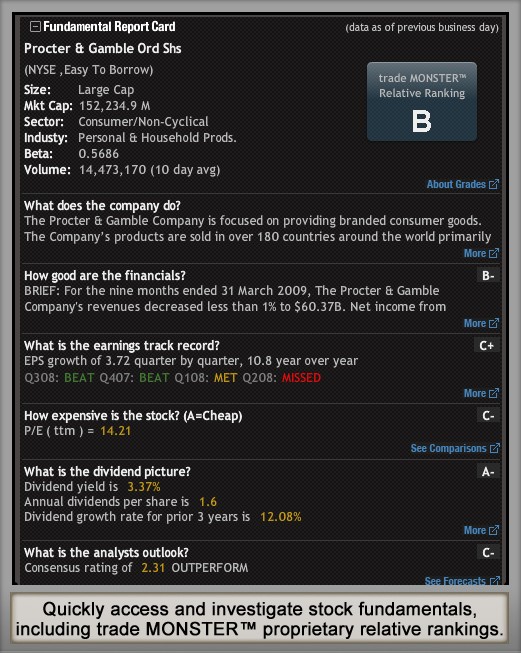

When searching for suitable stocks, you should focus on fairly volatile ones with strong fundamentals. Fundamental data may change among industries, so specific guidelines aren’t always helpful. For instance, a P/E ratio of 20 for a financial stock is probably expensive, but a solid technology stock with that same P/E might be a steal.

Try to find stocks with the following characteristics: quarterly earnings growth of more than 15 percent over the last two years, no debit or a debit-equity ratio of less than 1.0, and return on equity (ROE), assets (ROA), and invested capital (ROIC) of more than 15 percent.

The second key part is volatility, which represents how much the underlying stock moves (up or down) on a given day. More volatile stocks are ideal, because they have a better chance of reaching the short call’s strike by expiration. Stock candidates for this modified collar trade should have betas of 1.3 or higher.

But what about a revised collars downside risk after the long put expires? The answer involves a paradigm shift in how you should view this trade. Many traders place a stop loss order to control risk, but that is a static way to trade. Instead of simply entering a collar trade and hoping the market rallies, be ready to adjust it as market conditions change to exploit any trends (or lack thereof).

The difference between expiration months shouldn’t bother you, because you will likely adjust the trade before either option expires.

Trade example

Suppose you entered a revised collar trade on Apple Inc. (AAPL), which is a fundamentally strong company with quarterly earnings growth of 73.3 percent, no debt, and a return on equity of 27.5 percent — a sign of strong management. Apple Inc.’s stock price also reflects this as AAPL rose 18 percent in 2006 and soared another 91 percent in 2007 (as of Oct. 11). Placing this modified collar on Apple seems right, because many traders wouldn’t want to buy after such a large rally (see Figure 2).

To create this position, you could buy 100 shares of AAPL when it traded at $162.23 on Oct. 11, buy one January 2008 160 put for $16.10, and sell one April 2008 180 call for $16.20. The position’s net debit is $162.13 per share — $0.10 less because the short 180 call costs slightly more than the long 160 put. The trade risks $2.13 or 1.3 percent ($162.23 stock price + $16.10 put cost 160 put strike $16.20 call cost). Again, this risk is based on owning a put that gives you the right to sell Apple at $160 (until Jan. 19 expiration), even if it plummets to $10. If Apple rallies above 180, the trade’s maximum gain is $17.87 or 11 percent ($20 strike-price difference $2.13 risk). Its return-to-risk ratio is roughly 10:1, which is better than a standard collar ratio of less than 2:1. Table 2 lists the revised collar trades components, and Figure 3 shows its potential gains and losses on three dates: trade entry (Oct. 11, dotted line), expiration of the long 160 put (Jan. 19, dashed line), and expiration of the short April 180 call (April 19, solid line).

Managing the Collar Trade

Before you place the collar, you should decide when to exit, depending on if Apple rallies, trades sideways, or drops from Oct. 11 to April 19, 2008. If AAPL climbs above the short call’s 180 strike, that call will eventually be assigned, forcing you to sell shares to the call’s holder at $180. At that point, you will earn the collars maximum profit of $17.87. However, options that have time value remaining are rarely exercised, so you may have to wait several months. If Apple rallies strongly, there are a few ways to potentially capture more profits. If, for example, AAPL rose to $185, you could buy back the 180 call and sell another one at a higher strike and later-expiring month, a process called “rolling.” This generates an additional credit and allows you to profit from additional gains in the underlying. You could also sell the 160 long put as Apple advances.

There are only two scenarios where you truly need a protective long put: a bearish trend or prior to a fixed news event such as quarterly earnings reports. If AAPL stagnates and stays flat, the collar trade could run into trouble. The short call is the only collar component that helps here as it loses value due to time decay. The stock is going nowhere, and the long 160 put loses extrinsic value. For instance, if Apple trades flat over the next three months, the 160 put may expire worthless, while the short 180 call loses roughly $6 in time value (see Figure 2, lower line). If this happens, the collar trade may face interim losses of about $8, but that doesn’t mean you will lose money. Your maximum loss of $2.13 won’t increase as long as you wait until the 180 short call expires on April 19. You can always sell the long put and then wait for the short call to expire. Let’s assume Apple drops 25 percent after it releases disappointing earnings in early January and lowers its estimates for the upcoming quarter. If AAPL fell to $120, the long 160 put would have an intrinsic value of $40. The 180 short call would still have some time value, but most of it would disappear.

The following estimates assume three or four months have passed since entering the collar trade:

Apple at entry: $162.23

Current value: $120

Call at Entry: $16.20

Current value: $2.20

Total cost: $124.23 ($162.23 [$40.10-$16.10] [$16.20-$2.20])

You haven’t made any money if Apple trades at $120, and the position’s cost is $124.23, but you haven’t lost much either ($4.23 per share). Apple just got slammed, and you lost 2.6 percent ($4.23 / $162.13 original cost) — not bad. And if AAPL plunges, that doesn’t mean it won’t bounce back. Solid stocks occasionally fall sharply; anyone who watched stocks tumble in August and surge in September understands this.