A New Tactic for Investing in EmergingMarket Debt

Post on: 7 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Error.

September 1, 2012

There are few places investors won’t look in their search for yield and safety, and emerging-market bonds are the latest focus, attracting record inflows. But all that money has driven prices up and yields down, making investing tougher. It is time for a more nuanced approach.

Emerging-market debt has come a long way from the currency crises of the 1990s, which forced countries to be much more fiscally responsible. The average debt-to-GDP ratio (a measure of a nation’s economic health) for the developed world hovers around 100%; Japan is an outlier at 200%. Emerging markets, however, have a debt-to-GDP ratio of just 34%. Lower ratios mean an increased ability to repay debts.

As a result, emerging market is no longer akin to junk, and these countries are seeing their credit ratings upgraded. At the same time, developed markets (most notably, ahem, the U.S.) are getting downgraded. Nearly two-thirds of the JPMorgan Emerging Markets Bond Index Global Diversified is now investment-grade.

All this good news isn’t lost on investors, who have poured $13 billion into emerging-market bond funds this year, on top of $14 billion last year, according to Lipper. Small wonder, when you look at the average 5.6% yield of these funds, and the index’s 13% gain this year.

SOUND TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE? Maybe it is. Despite their strong performance and relative resilience, emerging-market bonds aren’t a safe haven, and money managers are becoming more cautious. Most of the recent investment has gone into dollar-denominated sovereign bonds, and fund managers say that finding opportunities there is becoming harder.

That leaves two other options—sovereign debt denominated in local currencies, which involves currency exposure, and corporate bonds, which aren’t as liquid as sovereign debt and often much more volatile.

The Brazilian real and Russian ruble appreciated earlier in the year, making those countries’ bonds less attractive. But now that those currencies are weakening, money managers are adding more local bonds to their portfolios.

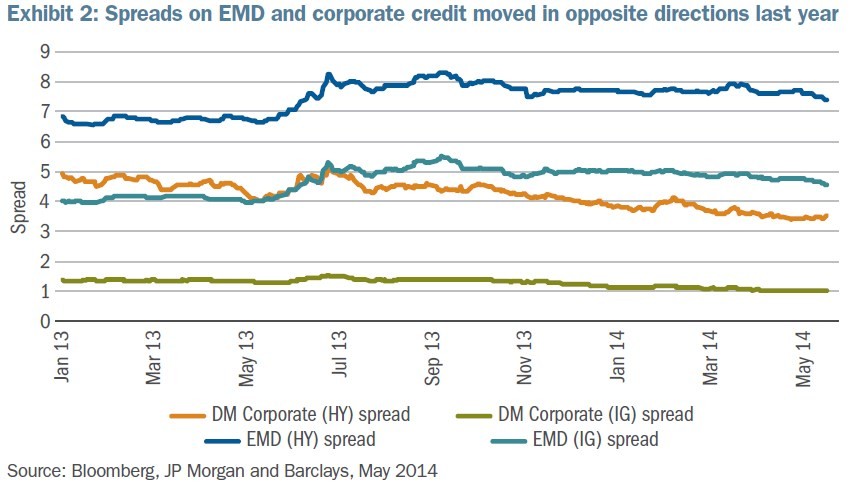

Corporate bonds are also becoming more attractive. When stacking up companies in the emerging markets against companies of comparable credit quality in the developed world, the emerging firms not only offer a richer yield—more than double—but also have cleaner balance sheets.

Local-denominated and corporate bonds also offer a different way to play these countries’ healthy fiscal and monetary positions, says Michael Conelius, who manages the T. Rowe Price Emerging Markets Bond fund (ticker: PREMX) and the new Emerging Markets Corporate Bond fund (TRECX). For example, bonds from the privately held Brazilian infrastructure firm Odebrecht allow investors to tap into increased government spending as the country tackles its infrastructure bottlenecks. Bonds from Turkey’s banks play into that country’s strong domestic demand, Conelius says.

TCW Emerging Markets Income fund (TGEIX) is another option; it can own all three types of bonds, and has sharply higher corporate exposure than its peers. It has returned 13% so far this year, beating 95% of its peers.

Investors should move with caution, but there’s still a good case for emerging-market debt, says Eric Stein, a portfolio manager on Eaton Vance’s fixed-income team: It’s not stretching if fundamentals are headed in the right direction and you’re getting paid for it.