A Critical Review Of Literature On Valuation Models Finance Essay

Post on: 1 Май, 2015 No Comment

This chapter starts with a definition of valuation followed by a brief history of equity valuation. The literature review provides insight into the strategic importance of valuation and the overview of valuation models. This chapter outlines the theoretical background of the main valuation models based on two main categories: the absolute and relative valuation approaches. The most popular models are explained including the Discounted Cash Flow, Dividends Discount Model and Residual Income Valuation in absolute valuation approach, as well as, Price to Earning, Price to Sales and Price to Book in relative valuation approach.

Valuation

Pinto et al. (2010) define valuation as ‘the estimation of an asset ’s value based on variables perceived to be related to future investment returns, on comparisons with similar assets, or, when relevant, on estimates of immediate liquidation proceeds’.

In equity valuation as the assumption is made that market price differs from the company’s intrinsic value. The intrinsic value approach was proposed by professors Benjamin Graham and David Dodds in their book Security Analysis published in 1934 following unprecedented losses on Wall Street (Graham & Dodds, 1934). They laid the foundations for the value investing which could be simply described as buying the securities whose shares appear to be underpriced, in other words buying stocks at less than their intrinsic value. Benjamin Graham taught Warren Buffet and not surprisingly Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway contributed to further development of the value investment concept.

The intrinsic value is calculated with the use of some form of fundamental analysis, which according to Penman (2004) is the method of analysing current and past financial statements and macroeconomic, industry and firm’s specific information in order to arrive at a firm’s intrinsic value. Therefore the main purpose of fundamental analysis used by investors is to identify mispriced stocks.

A brief history of equity valuation (2-3 p.)

For many decades academics and investor were searching for a valuation method giving the most predictable investment results. In 1930’s Benjamin Graham and David Dodd proposed fundamental analysis based on the Price to Earnings (P/E) multiple as a valuation tool for identifying the investment opportunities (Graham & Dodds, 1934). The multiples based valuation techniques have been developed over years with a variety multiples introduced, such as, Price to Sales (P/S), Price to Book (P/B) or Price/EBIT, and are one of the most widely used valuation approaches today (Damodaran, 2002).

Another valuation theory with a long history, the Residual Income Model (RIM) has its roots is the residual income approach originally proposed as an economic concept by Alfred Marshall over a century ago (Marshall, 1890). The residual income was the used to evaluate business segments since early 20th century and recently gained a renewed popularity in evaluating variety of contexts, such as, measuring company’s performance or residual income valuation (Lee, 1996).

Following the market crash in 1929 and American economist John Williams in his text The Theory of Investment Value laid the foundation of the discounted cash flow valuation (DCF) and in particular Dividend Discount Model (DIV) (Williams, 1938). In his model the stock valuation was based on the idea of discounting constant stream of cash flows to infinity. Dividends that investors would receive were used in the cash flows calculations. This model was later extended by another American economist Myron J. Gordon with his introduction of a Dividend Growth Model allowing the dividends to grow at the constant forecasted rate (Gordon, 1962).

More recently there was a significant expansion in research in estimating the value of the firm (Vf) with the introduction of the valuation model based on Free Cash Flow to the Firm (FCFF) proposed by Tom Copeland, Tim Koller and Jack Murrin in 1990 in their book Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies (Copeland, et al. 1990). Four years later the same authors, introduced the concept of valuation based on Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE), further evaluated by Aswath Damadoran (Damodaran, 2002).

The concept of free cash flow became the core of modern valuation techniques. Copeland, et al. (1996, p.172-173) define the basic free cash flow as ‘a company’s true operating cash flow which includes all investment in new capital but without considering new debt. It is the after-tax cash flow generated by the company and available to all providers of company’s capital, both creditors and shareholders’.

Most recent years show the expansion of Real Options Approach (ROA) used to value the firms with no comparables, or with a limited availability of data for analysis (Amram & Kulatilaka, 1999), (Copeland & Antikarov, 2001).

Strategic importance of equity valuation (1-2 p.)

Valuation is an important tool for organisations strategy and many strategic decisions are based on information derived from valuation outcomes. For example mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, spin-offs, and going private transactions require the use of valuation tools (Pinto J. E. et al. 2010). Also, in most cases there are third parties, such as banks involved in those processes, requesting detailed financial profile of organisations involved.

Companies use valuation to evaluate the impact of new business strategies on their share value. This information is important to shareholders and companies concerned with increasing shareholders value.

Other strategically important users of valuation include private businesses considering initial public offering (IPO). According to Draho (2004) valuation is a ‘necssary and critical part of going public process’.

There are many applications of valuation in business practice and not surprisingly the methods used differ according to the areas they are applied to and the main purpose they are designed to serve. One of strategically important application of valuation refers to company planning investing in stock market. The focus of this paper will be on application of valuation models in those investment decisions where the management wants to know if the security they invest in is ‘fairly priced, overpriced, or underpriced relative to its current estimated intrinsic value and relative to the prices of comparable securities?’ (Pinto J. E. et al. 2010).

An overview of equity valuation models

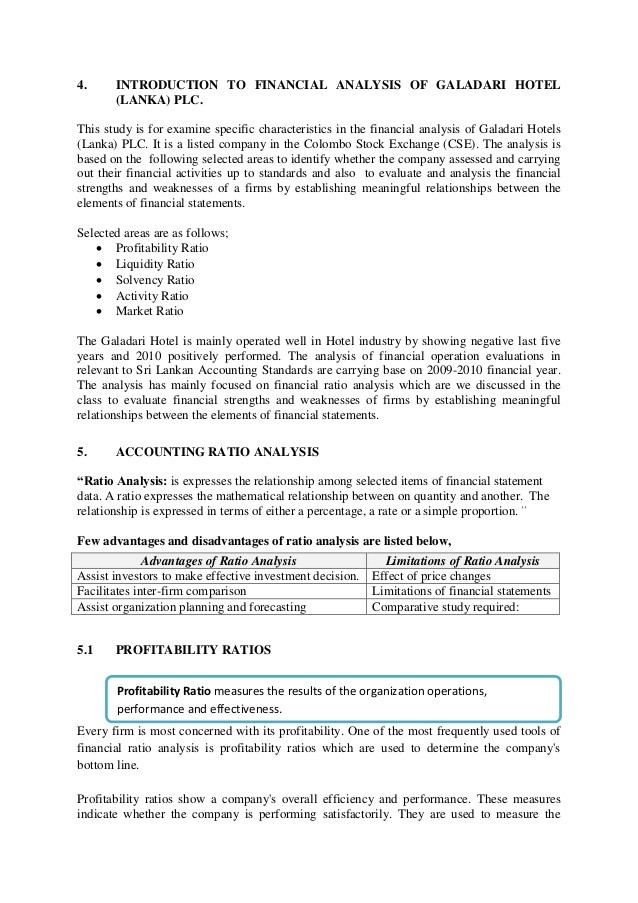

Analysts use two broad approaches to valuation — absolute and relative valuation models (Andrew Metrick, 2010). Absolute valuation models specify assets’ intrinsic value, while relative valuation models specify assets’ value relative to another asset.

Absolute valuation models

Absolute valuation models are used to specify the assets’ intrinsic value which is most often compared with the asset’s market price (Pinto J. E. et al. 2010). This type of valuation is mainly based on the present value (PV) models which are fundamental concepts in equity valuation. Those PV models often referred to as discounted cash flow (DCF) models assume that the discounted value of future cash flows that investor expects to receive from holding the asset gives the representation of the value of that asset. At the shareholder level the cash flows could be calculated as the flow of dividends distributed to shareholders using the dividends discount model (DDM). The cash flows could be also defined on the company level with free cash flow (FCF) and residual income (RI) representing the two most popular approaches. Free cash flow is the company’s true operating cash flow and there are two main models based on the FCF (Copeland, Koller, & Murrin, 1996). First, the free cash flow to equity (FCFF) model considers cash flows after the payment to the providers of debt, while the second approach, the free cash flow to the firm (FCFF) excludes those payments. Residual Income models (RIM) calculate accrual accounting income net of the opportunity cost of generating that income. Benninga (2008) identifies opportunity cost as the basic concept in present value calculations and defines it as the required investment return that would make it a viable alternative to other investments.

The present value models are complex and mostly challenging in practical application. Sensitivity analysis is used in order to manage the variety of assumption that the analyst has to make. Sensitivity analysis is simply an analysis of the extent to which the change in the assumptions affects the change of the outcome.

The asset-based valuation (ABV) is an example of another type of absolute valuation and simply calculates the market value of the assets and resources that the company controls. This type of valuation is mostly applicable to the companies involved in natural resources extraction and production, such as those in the mining, or oil & gas producers sector.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method was formally used since 1930’s defined by Irving Fisher’s in book The Theory of Interest and John Burr Williams’ text ‘The Theory of Investment Value’. Discounted Cash Flow model is based on the concept of time value of money in which view ‘the intrinsic value of common stock as the present value of its expected future cash flows’ (Pinto J. E. 2010). All estimated future cash flows are discounted (usually using the weighted average cost of capital — WACC) to their present value (PV) and summarised as Net Present Value (NPV). This is derived from the assumption that the same amount of money (e.g. £100) today is worth more than if received in the future. The equation for the present value of the monetary unit received in one year’s is:

(2.1)

C = Monetary Unit

t = Discount Rate

Formula (2.2) shows that the present value of £100 received one year from now at the 10% discount rate is worth £90.91 today:

(2.2)

Free Cash Flow Model (FCFM)

In DCF valuation the future cash flows are calculated over multiple periods. The basic equation for DCF based on free cash flows (FCF’s) earned in the period t is:

(2.3)

FCF = Free Cash Flow [1 ]

t = Discount Rate (WACC)

or simplifying the equation:

(2.4)

Formula (2.4) assumes that there is an infinite number of projected free cash flows, which is not practical and difficult to model. Therefore, financial analysts most often use a finite number of years for which the free cash flows are projected and a terminal value of the firm after this projected date (Benninga, 2008). The equation for an enterprise value with a typical 5 years free cash flow projection is:

(2.5)

EV = Enterprise Value

TV= Terminal Value

According to Benninga (2008) the terminal value calculation is based on the assumption, that after the cut off date for FCF (5 years in the above example), the ‘year-5 cash flow will continue to grow at a constant long-term growth rate’ (Benninga, 2008; p.114). The equation for the terminal value at the end of year 5 is:

(2.6)

FCF5 = Free Cash Flow in Year 5

gFCF = Long-term FCF growth rate

As noted earlier the future cash flows are usually discounted to their present using the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) as a discount rate. WACC is the ‘required rate of return of the company’s suppliers of capital’ representing creditors and common stockholders (Pinto J. E. 2010; p.76). The equation for WACC condsidered to be nominal after-tax weighted cost of capital is:

(2.7)

MVD = Current market value of debt (not book or accounting value)

MVCE = Current market value of common equity (not book or accounting value)

r = Required return on equity

rd = Pre-tax rate — before tax required return on debt

Taxr = Marginal corporate tax rate

The sum of MVD+MVCE gives the total market value of the firm, and therefore,

is the proportion of the total company’s capital from debt, and similarly, is the proportion of the total company’s capital from equity [2 ] (Pinto J. E. 2010).

Corporate interest payments are tax deductible which is reflected by downwards tax adjusting the pre-tax required return on debt rd. In contrast the distribution of equity is not deductible and therefore no adjustment is required for the required return on equity r.

In conclusion, free cash flow valuation is based on three fundamental variables: cash flows, terminal value and the discount rate.

The main criticism of free cash flow valuation is that it depends upon ‘uncertain future forecasts’ which often render inaccurate intrinsic value calculation results (Vardavaki & Mylonakis, 2007). Also, FCFM process ignores accrual accounting, and therefore, fails to recognise short term value addition (Penman S. H. 2004). Another problem with FCF valuation relates to difficulty in model aplication to firms with high capital expenditure, such as fast growing firms, which may render negative FCF, and therefore, negative intristic value of the equity (Pinto J. E. 2010).

Dividend Discount Model (DDM)

Dividend Discount Model

The main criticism of DDM is that it does not recognise the internal growth through retained earnings which many young rowing firms may experience. The model also has no applicability in cases where companies do not pay dividends or decide to freeze paying dividends in foreseeable future (Pinto J. E. 2010). Another criticism is that DDM depends on the forecast of dividends payout to infinity for going concerns, which is a problematic assumption and difficult to justify as the basis of information about company’s value after a finite horizon (Miller & Modigliani, 1961). Those two weaknessed of DDM model relate to the assumption that the value generation is in direct corraltion with cash distribution to shareholders. The example where this assumption doas not hold true is a case where a company borrows money to pay dividends (Penman, 2004).

Residual Income Model (RIM)

The Residual Income Model (RIM) is based on the assumption that the intrinsic value of the firm is equal to the sum firm’s equity book value and present value of the expected future residual income. Pinto, at al. (2010) define residual income as the residual (remaining) income in excess of the cost of all company’s capital, and therefore, it is net income reduced by the ‘common shareholders’ opportunity cost in generating net income’ (Pinto J. E. 2010; p.210). The cost of the company’s debt capital is reflected in the income statement as the interest expense. However, the cost of equity capital is not recorded in company’s financial statements, and therefore, the company with positive net income may not be adding value for shareholders if its earnings are not sufficient to cover the cost of equity capital [3 ]. The opposite is true, which is that the company is adding value when is generating more income (positive residual income) then the cost of obtaining all company’s capital (O’Hanlon & Peasnell, 2002).

According to Ohlson (1995) the residual income equation is:

(2.8)

RIt = Residual income at time t.

NIt = Net income for period ending at time t.

r = Required return on equity (cost of equity)

Bt-1 = Book value of common equity at time t -1.

An accounting identity, called clean surplus relation, states that the changes in book value of the company in the fiscal period are reflected in the earnings (net income) for the period and dividents distributed (O’Hanlon & Peasnell, 2002). The ending book value of the company can be measured as a sum of the begining book value and earnings, less dividends. This can be summarised by the equation:

(2.9)

Bt = Book value of common equity at time t .

Bt-1 = Book value of common equity at time t -1

NIt = Net income for period ending at time t (period from t -1 to t )

Dt = Cash dividend paid to common shareholders at time t .

The residual income model measures the intristic value of equity as the sum od the current book value of equity and the present value of the forecasted future residual income. The equation for RIM valuation is (Ohlson, 1995):

(2.9)

V0 = Value of a share of stock today ( t = 0)

B0 = Current per-share book value of equity

Bt = Per-share book value of equity expected at time t.

r = Required return on equity (cost of equity)

Et = expected earnings per share (EPS) for period t.

RIt = Expected per-share residual income [4 ]

ROEt = Return on equity

One of the biggest strenghts of residual income valuation models is that they are based on data included in the financial statements which is readily available. Also, those models can be alpplied to companies not paying dividents, those with negative short term free cash flows, or those with unpredictable cash flows (Pinto J. E. 2010). The main weaknesses of RIM include the reliance on accounting information which can manipulated by management, and the fact that the data used may require analyst to make significant adjustment, for example, when the clean surplus relation does not hold (Gode & Ohlson, 2006).

Asset Based Valuation

Relative valuation models

Relative valuation methods are valuations based on multiples and specify an asset’s value relative to that of another asset (Pinto J. E. et al. 2010). The assumption is made that similar assets should be similarly priced and the valuation involves using price multiples. A multiple is simply a ratio of market price variable (e.g. stock price) to a particular fundamental (e.g. earnings or cash flow per share) which is a value driver of a firm.

The most common multiple is the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E), which represents the ration of the market price of the company’s stock to the company’s earnings per share. For two similar companies if P/E of one is lower than the P/E of another then the first one is relatively undervalued compared to the other. This would suggest that the first one is a better buy then the second one. It is important to note that relatively undervalued asset can be overvalued in absolute sense of the intrinsic value is higher than the market price (and vice versa). In order for relative valuation to result in the calculation of the intrinsic value of the asset an analyst needs to make an assumption that the asset used as the base for comparison is fairly priced. This adds the complexity to multiple based valuations and requires the analyst to carefully select most often a group of the companies being compared based on many similarities (e.g. size, risk growth rates).

In contrast to absolute valuation models, the multiples based valuation does not require detailed financial statement forecasts. The simplicity of the relative valuation methods is the primary reason behind their popularity. According to Demirakos, Strong and Walker (2004) 67% of valuations models in analysts’ reports are based on multiples, while only 16% on DCF, 10% on RIV, and remaining 7% based on other models. Multiples valuations require fewer assumptions and can be completed faster than other valuation methods. In addition they are relatively easy to understand and present to customers.