Woe Betide The Value Investor

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Research Affiliates is a value shop in the tradition of Ben Graham’s investment philosophy. As investors, we sell the popular securities that have become overpriced and we bargain-hunt for assets that have fallen out of favor. Today, however, we must acknowledge an inconvenient truth. The excess return earned by the average value mutual fund investor has been meaningfully negative.

What’s going on? How does this recent experience jibe with decades of research on the value premium? Does the negative excess return earned by value investors arise from an unrepresentative measurement period? Perhaps fees for the average value mutual fund are so high that they more than offset the value premium. The answer will not only surprise you but suggest tremendous opportunities for truly contrarian value investors. But first, you will have to suffer through a few more paragraphs to learn the punchline. After all, we do have word count targets to make.

The Value Anomaly

Value is the undisputed champion of investment anomalies. According to academic and practitioner research, value strategies have consistently delivered a premium over the capitalization-weighted market portfolio for the last 90 years. Investors have known about the benefits of value investing for nearly as long. Ben Graham and David Dodd popularized the approach in their 1934 classic, Security Analysis. The legendary Warren Buffett has practiced and preached long-term value investing for his entire career, now spanning more than 50 years. Basu (1977) rigorously documented the value premium. Fama and French (1992) constructed the value factor (HML), propelling value investing into the core curriculum of every business school and the value factor into every investment analytics system.

Value investing is thoroughly documented, well publicized, and widely endorsed. This raises obvious questions: Why isn’t everyone a value investor? Why hasn’t the smart money arbitraged the effect away? Clearly, it is not possible for everyone to be a value investor; someone has to be on the other side of the trade. Who, then, willingly or unwillingly, invests against value? Can there be so many financially naïve investors? And how many more naïve innocents can we count on to generate a meaningful value premium in the future? This last question is perhaps the most important as it casts doubt on the investment capacity of one of the most popular investment strategies.

Believers in the efficient market hypothesis see value stocks as risky and undesirable. Value investors are extracting a risk premium. But many practitioners who are familiar with investor psychology think of the value anomaly as a mistake that institutions and individuals make for a host of behavioral reasons. The two camps can argue endlessly. We have nothing to contribute to that disagreement. Nonetheless, both sides have a key assumption in common: Long-horizon value investors outperform (just for different reasons). What we show in this issue of Fundamentals is the contrary fact that so-called value investors have substantially underperformed the S&P 500 Index for the last 30 years. There is no evidence that mutual fund investors are extracting a positive value premium either by (1) bearing risk or (2) by exploiting other investors’ behavioral mistakes.

Investors’ Performance

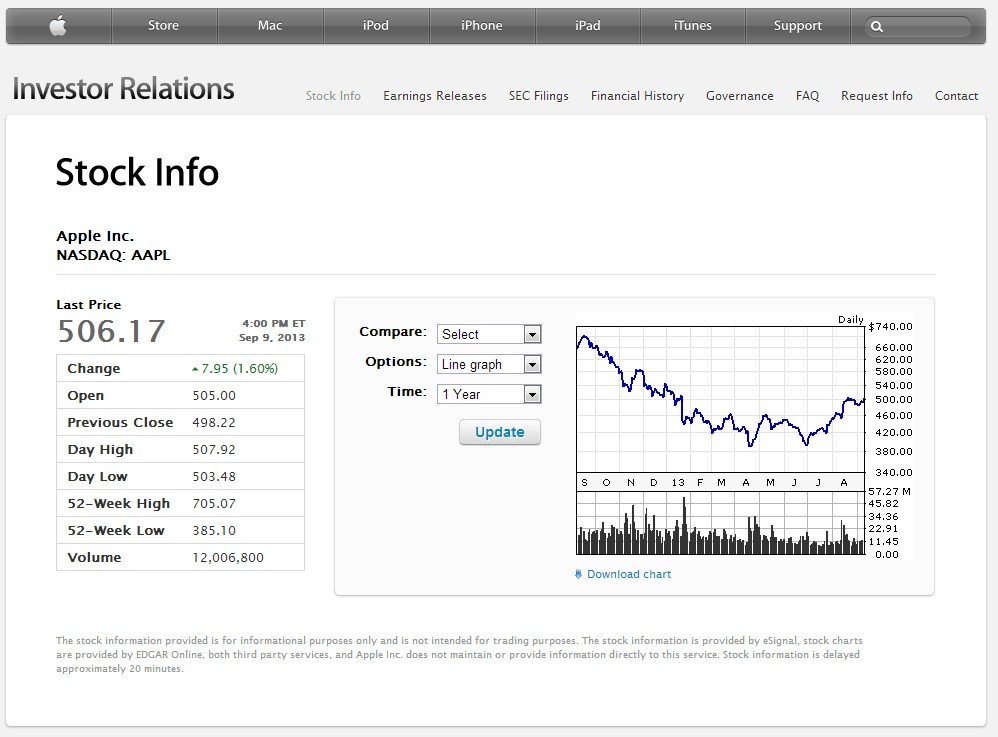

Examining the entire available history of mutual fund performance, Hsu, Myers, and Whitby (2014) find that the average value investor didn’t earn anywhere near the reported value premium (Table 1 ). In fact, he or she underperformed the S&P 500 meaningfully, even before taking fees into account. How is this possible?

For a larger view, please click on the image above.

While it is true that, on average, value managers and value mutual funds outperform the S&P 500 (by 39 bps), their time-weighted rates of return don’t translate into outperformance for the investors. In fact, the average value investor underperforms a buy-and-hold investment in the S&P 500 by –92 bps. Value fund investors typically do not hold their investments. Instead, they chase trends, allocating away from value funds after a period of underperformance and towards them after a period of outperformance. In other words, average value investors do not adhere to the contrarian allocation as one would expect; they are actually trend chasing. Unfortunately for them, however, the value premium is mean-reverting. After periods of outperformance it tends to underperform, and vice-versa. Trend-chasing investors increase their allocation to value funds before (and sometimes just before) the funds reverse direction and head back, downward, toward their long-term averages. And they reduce their allocation before the funds head up again. This poor timing has cost value investors an average of –131 bps per annum.

If you are both an academic and a portfolio manager, you may wish to examine the meaning of your life. It could be argued that both your students and your clients would be better off if they hadn’t learned about the value premium and just stayed with an S&P 500 fund as Burt Malkiel and Jack Bogle have passionately advised.