Why Low Beta Stocks Are Like Bonds For Dividend Growth Investors

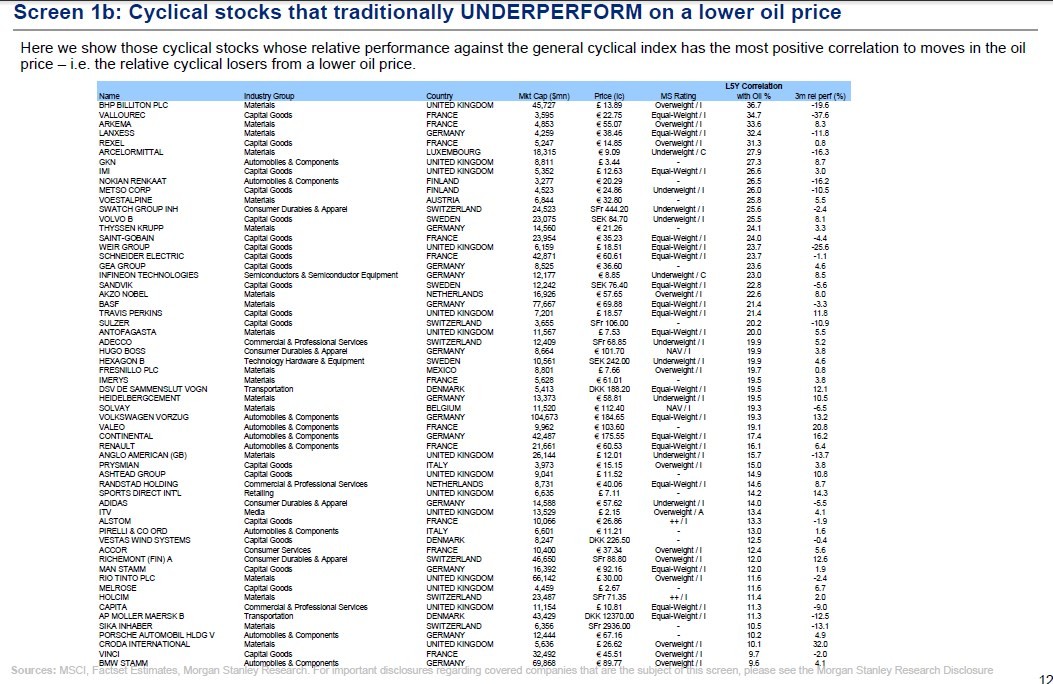

Post on: 14 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

I was reading a paper on Modern Portfolio Theory [MPT] yesterday, and I realized something so obvious that I am embarrassed that it did not occur to me before.

In the paper (Modern Portfolio Theory, Part One ), by Donald R. Chambers, who is the Walter E. Hanson/KPMG Professor of Finance at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, the author was making some points about the role of bonds in an asset-allocated portfolio. He began with a description of asset allocation.

How much of your portfolio should you place into various categories of investments? In a nutshell, this is the asset allocation decision. It concerns how much money to place into risky investments such as the stock market, and therefore how much remains to be placed in safe investments such as money market mutual funds and certificates of deposit. In practice, many people view the asset allocation decision as determining investment levels in several categories of risky assets such as stocks, real estate and hedge funds. Some people may further subdivide a category such as stocks into subcategories such as international vs. domestic, small cap vs. large cap, growth vs. value and so forth. But for our purposes here, the asset allocation decision concerns just two major asset classes: risky investments and safe investments.

Since the paper is about MPT, the author uses MPT’s definition of risk, namely price volatility. Dr. Chambers goes on to discuss the common 60-40 portfolio, where the allocations are split between 60% risky assets (i.e. stocks) and 40% safe assets (i.e. bonds).

This 60/40 split is often considered to be the typical split for the pension money of a financially comfortable investor well prior to retirement. If the stock market quickly rises or falls 10 percent, [the investor’s] total portfolio will tend to move only 6 percent. Why? Her stock positions comprising 60 percent of her portfolio will rise or fall the same amount as the market, but her low-risk bond funds will barely move.

Chambers goes on to assert that any portfolio can be compared to any other along this dimension, namely the relative movement of the portfolio in relation to the market. Given MPT’s definition of risk, this relative movement is a measure of the comparative risks in the two portfolios.

Many investors hold assets other than stocks and bonds, and the author addresses this. He believes that for risk assessment, measuring the portfolio’s typical behavior relative to the stock market is a sufficient metric.

Granted, sometimes it is difficult to classify a total portfolio solely in terms of the percentage stocks and percentage bonds. But for our purposes it is helpful to assume for simplicity that each investor’s portfolio can be approximated by a simple mix of stocks and low-risk bonds. This assumption is not as restrictive as it may initially seem. Almost every asset allocation can be viewed as having an exposure to the stock market that is similar to the exposure of a particular combination of stocks and bonds. In other words, an investor might hold multiple asset classes (e.g. corporate bonds, real estate), but the portfolio can still be viewed as having the same market risk as a pure stock and low-risk bond portfolio by answering the following question: If the stock market were to fluctuate quickly either up 10 percent or down 10 percent, how much would the portfolio typically rise or fall? A reply of 6 percent is comparable in market risk to the previous asset mix of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds.

I want to focus on the phrase exposure to the stock market. In MPT, stocks are risky assets. The reason they are risky is that their prices fluctuate. MPT considers price fluctuation to be the risk in investing. Lack of price fluctuation = safety.

Bonds, in contrast to stocks, are seen as safe. What is safe about bonds? If you own an investment-grade bond, you own a contractual right to receive from the issuer, at the end of the bond’s term, all of the money that you lent the issuer to purchase the bond. That is the end-game for a bond: After the last interest payment has been made, you get your original investment back.

So what Dr. Chambers is saying is this. If you own stocks, you are exposed to market risk. If your portfolio is 100% stocks, you are 100% exposed to market risk. But if your portfolio is 60% stocks and 40% bonds, the bonds are not exposed to market risk. So your portfolio is safer.

In fact, the proportion of stocks to bonds can be used to define its safety: If 40% of your portfolio is bonds, then it is only 60% as risky as an all-stock portfolio. (The risk under consideration is market risk, namely the volatility of the stock market. Idiosyncratic risk-all price volatility that does not emanate from market risk-is being ignored here.)

[C]onsiderable insight can be derived from viewing all portfolios as having a level of systematic risk that is equivalent to being some percentage, say x percent, in the overall stock market and therefore (100-x) percent in short term, low default risk bonds (i.e. the so-called riskless asset). This variable, x (expressed as a decimal such as 0.60 or 1.20), is called the beta of the portfolio and is the measure of market risk. So a portfolio that has 60 percent stocks and 40 percent risk-free bonds, and any portfolio with a similar level of market risk, is said to have a beta equal to 0.60. A portfolio entirely invested in a broad stock market portfolio would be said to have a beta of 1.0. Money market funds have a beta of 0.0 [meaning that they do not move with the stock market at all]. The concept of beta can be applied to individual stocks, mutual funds and overall portfolios.

We all know that, as Chambers says, beta is a metric that can be derived for individual assets as well as entire portfolios. In fact, that is where we usually encounter it. Morningstar displays beta on the quote (HOME) page for every stock in its database. Seeking Alpha displays beta for individual stocks (calculated over 3- and 5-year periods) if you set up a portfolio in its portfolio tool. David Fish displays 5-year beta for each stock in his Dividend Champions document. Below are screen shots of these sources.

Morningstar:

Seeking Alpha :

(Click to enlarge)

Dividend Champions:

All right, you may be wondering where am I going with this?

We frequently see commentary in SA and elsewhere that a major role-if not the principal role-of bonds in many investors’ portfolios is to mitigate risk, meaning to dampen the volatility of the portfolio. I have seen it said that it is necessary for many investors to hold bonds, because the bonds temper portfolio volatility to a level that they can tolerate.

If they can tolerate the volatility, they can stay the course. That is important, because over-trading has been shown in studies to be the principal reason that many investors underperform the very assets that they invest in. They sell low when the market dips, then buy back high when the market recovers. This behavior is more psychologically driven than rational, and it hurts returns.

This is where I had my aha moment. Why should bonds be considered necessary to reduce beta and dampen portfolio volatility compared to the market, when other assets that have low beta can accomplish the same thing? For example, can’t you achieve the same level of volatility with low-beta stocks?

Looking only at volatility, I don’t see any difference between a portfolio whose volatility has been reduced by adding bonds and a portfolio whose volatility has been reduced by holding low-beta stocks.

Of course, in constructing a portfolio, many factors need to be considered, all of which should proceed from your goals. But for dividend growth investors who have no (or few) bonds, I would suggest that you don’t need to be swayed by suggestions that your portfolio is too risky because of the absence of bonds. I would also suggest that the prevailing view, that in order to be properly balanced a portfolio must hold bonds, is far too general. You can achieve a portfolio-wide beta of 0.6 with an all-stock portfolio.

Here are the betas of the most widely held dividend growth stocks from my survey a few months ago. I made a Seeking Alpha portfolio out of the 59 stocks. The betas are at the far right. Sorry, I needed to break it up into three screen shots; all of the stocks would not fit into one screenshot.

You will see that lots of these stocks have betas below 0.6. It is not hard to construct a dividend growth portfolio that has an overall beta of 0.6 or 0.7 if market volatility is a significant concern for you.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)