What s an Expense Ratio

Post on: 25 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

If you’re reading this, chances are that you’re one of the more than 91 million Americans with an average of $48,000 invested in mutual funds. But do you know how much you pay to stay invested?

If my neighbors and family are any indication, you don’t. So today, we begin a new series to introduce you to mutual fund basics, beginning with the all-important expense ratio.

What it is

According to brokerage Edward Jones, an expense ratio is annual operating expenses divided by average annual net assets. That is, you take the costs of running the fund and divide them by the value of the assets under the purview of the fund’s managers. The result is expressed as a percentage.

Some funds sport remarkably small expense ratios, such as the Vanguard 500 Index ( FUND: VFINX ). which charges just 0.18% as of this writing. Others, such as the gimmicky and politically inclined Blue Small Cap Fund. allow expenses to eat 1.75% of assets.

But a smaller ratio is better, says Motley Fool GreenLight co-advisor and Motley Fool Champion Funds lead analyst Shannon Zimmerman. An expense ratio is the percent of your assets a fund company takes back each year in exchange for its services, he says. It’s the fund’s price tag, in other words, and it comes right out of returns that would otherwise flow to you. All else being equal, then, the lower a fund’s expense ratio, the better. But all else isn’t equal, of course.

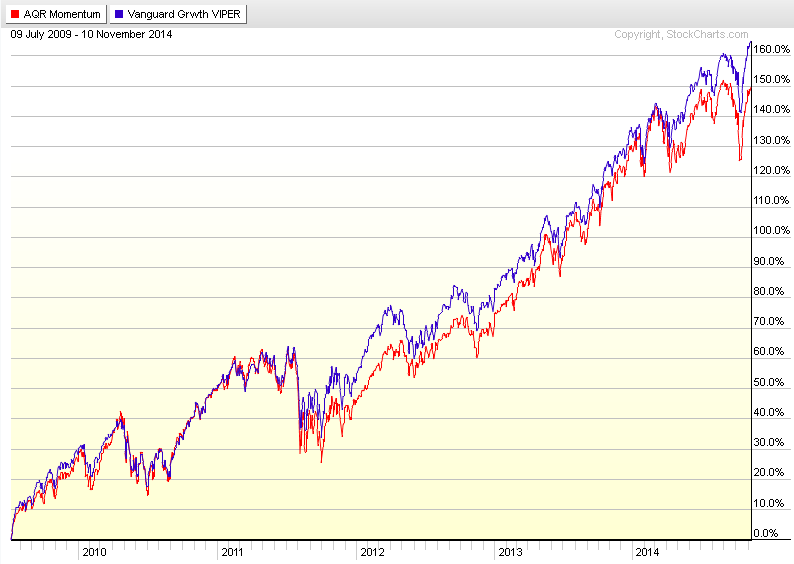

Indeed, the numbers suggest that most managed funds — namely, any fund that doesn’t mimic an index such as the S&P 500 — won’t beat the wider market, regardless of the underlying price tag. Therefore, paying less for quality merchandise only makes sense.

How it works

Let’s put this principle into practice. According to Yahoo! Finance, you’d pay approximately $230 over 10 years on a $10,000 initial investment in the Vanguard 500 index.

Pretty cheap, right? Sure, but it looks even cheaper when compared with the average large-cap value stock fund, which Yahoo! Finance estimates will cost you $1,856 to hold for a decade. And that’s before the front-end and back-end sales charges that accompany most stock funds.

The expense ratio is the primary problem, however. Because the average large-cap value fund charges 1.17% more than the index, it has to outperform by at least that much to create value for investors — and more (maybe a lot more) if sales charges are involved. That’s a high hurdle for fund managers, many of whom trip and injure their clients’ portfolios in the process.

Go under the hood

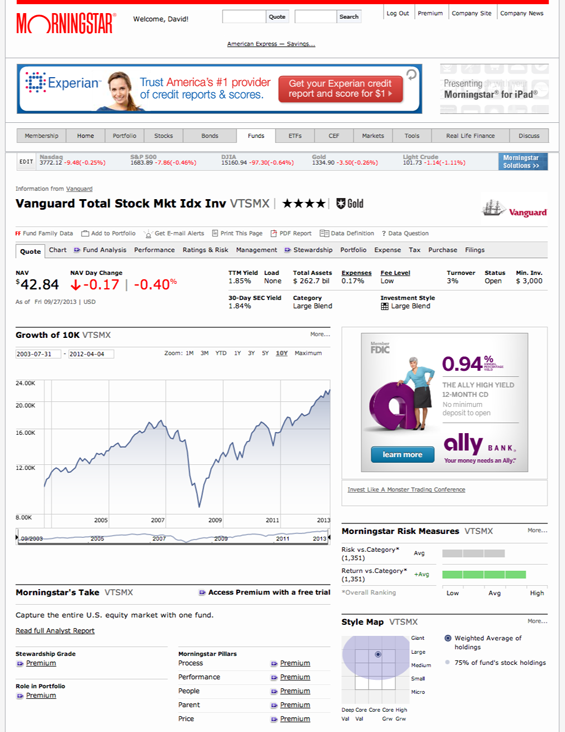

Are you one of them? There’s an easy way to find out. At Morningstar.com, click first on the funds tab and then use the selector on the left side of the page to find your fund’s family. Choosing Fidelity, for example, will get you a list of all Fidelity products. Choose your fund; then, in the left navigation bar, select total returns.

There, you’ll find your fund’s average annual performance over the past year, three years, five years, and so on. Check your results against the benchmark and category. Then, subtract the expense ratio from the difference. That will tell you whether you’re holding a value creator, or a value destroyer.

Let’s use another example. Fairholme ( FUND: FAIRX ). which Shannon has chosen for Championship status, is up 6.76% on the S&P over each of the last three years and 9.18% annually over the last five years, according to Morningstar. Subtract Fairholme’s reasonable 1% expense ratio, and you’ve got a fund that’s been an extraordinary value creator.

Follow the money

Keeping fund fees low is a great way to make the most of your money. It’s also one of the keys to doubling your savings each decade, as Shannon and co-advisor Dayana Yochim illustrate with a slew of tips in the monthly pages of GreenLight. Want to learn more? Click here for 30 days of free access to the service.

And in the meantime, write me if you have a story or a money tip worth sharing. You’ll be helping your fellow Fools, and you’ll earn a modicum of fame that money can’t buy. How’s that for a bargain?

Fool contributor Tim Beyers owns only two funds, and they don’t charge him much. Tim didn’t own shares in any of the companies mentioned in this article at the time of publication. Get a peek at everything he’s invested in by checking Tim’s Fool profile. The Motley Fool’s disclosure policy is a bargain at any price.