What Mutual Fund Investors Need To Know About The New 2012 Tax Rules

Post on: 17 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Follow Comments Following Comments Unfollow Comments

If you’ve received unfamiliar paperwork from your mutual funds or brokers recently, you’re not alone. New IRS rules require your custodian to know how you’d like the cost basis of your funds to be calculated because, starting in 2012, they’re required to report your cost basis to the IRS.

Cost basis is the amount you paid for an investment, plus reinvested dividends and capital gains distributions. This amount is the basis for determining how much you’ve gained or lost from an investment; the difference between the cost basis and the sale price of the investment equals your taxable gain or loss.

If an investment is sold for more than the cost basis, then there is a realized capital gain. If an investment is sold for less than the cost basis, then there is a realized capital loss. In a taxable account, both realized gains and losses are reported to the IRS. (Retirement accounts are exempt from cost basis reporting.)

What’s Changing in 2012

Previously, custodians only had to report the gross proceeds of the sale of securities to the IRS; it’s been up to you, the account holder, to determine how to calculate gain or loss when you filed your tax return.

But starting in 2012, your broker or fund company will submit a 1099-B form that spells out your cost basis and your gains and losses. Schwab has a detailed example of their new 1099-B tax form available online. Remember that this new requirement only affects shares purchased on or after January 1, 2012 in a taxable account.

Understanding Your Cost Basis Election Form

Most cost basis election paperwork refers to “covered” shares and “uncovered” or “non-covered” shares. Covered shares are the shares that are covered by the new regulations (those bought after January 1, 2012). Uncovered shares purchased prior to that date are not covered by the new reporting rules. Custodians will not have to report the cost basis to the IRS on uncovered shares, even if they are sold after January 1, 2012.

You may end up with two different cost basis: one that you report to the IRS for shares bought before January 1, 2012, and one that your custodian reports to the IRS for shares purchased after January 1, 2012. Most cost basis election forms refer to this as “bifurcating” your account. This means that, internally, your broker or fund company will track your shares in two buckets: the non-covered shares in one bucket and the covered shares purchased after January 1 in another.

Many Ways to Calculate Cost Basis

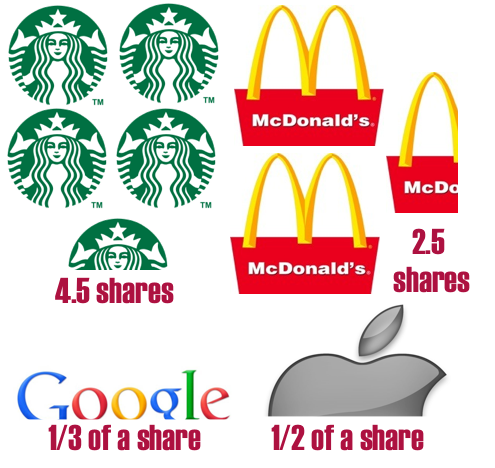

Cost basis sounds straightforward, but there are a few variables to consider. As an example, consider an investor who bought 100 shares of say, Fidelity Contrafund each month from January to June, ending up with 600 total shares. The following January, the investor puts in an order to sell 100 shares, but which 100 shares (or “trade lot”) should the broker sell?