The Wrapfee Account Worth What It Costs In Theory It Offers Individual Investment For A Set

Post on: 18 Июль, 2015 No Comment

By Jeff Brown, INQUIRER STAFF WRITER

Posted: August 08, 1993

Ask a ball player his batting average, he’ll tell you.

But try asking a stockbroker or financial adviser how much money he’s made for clients. You may get hyperbole: The up years came from his smart stock- picking, the down ones from market forces outside his control — like a losing pitcher blaming his outfield.

The perennial question of whether financial advice is worth what it costs is at the center of a growing debate over one of the hottest new investment vehicles in the securities industry: the wrap-fee account.

In theory, wrap accounts give customers professional, individualized portfolio management they could not otherwise receive. A brokerage firm helps the customer set up the account and define investment goals, then turns over its management to an outside professional who does the trading. A single fee, typically 3 percent a year, covers all trading commissions and administrative costs.

Critics, however, charge that wraps are no more than a slick new technique for siphoning unnecessary fees from investors’ accounts. Once the management fee is subtracted, they say, it’s virtually impossible for the average wrap account to beat a simple, inexpensive mutual fund that tracks the overall performance of the market.

Wraps, says Theodore R. Aronson, principal of Aronson & Fogler Investment Management, are a massive transfer of real wealth from investors to brokers. Aronson’s Philadelphia firm manages institutional investments such as pension funds, but not wraps.

But wrap proponents say an excessive focus on fees obscures the point: that wraps are services, not products.

For me to say I’m in the wrap-fee business is like a doctor saying he’s in the medical-billing business, says Dennis Bertrum, director of investment-management services at Prudential Securities, which has $4.5 billion in its wrap accounts.

You pay a fee for what we call relationship management.

Prudential’s average wrap-account holder is 59 years old, has $900,000 in liquid assets and often feels uncomfortable making investment decisions without professional help, he says. Most want help minimizing risk, a criterion he says often is overlooked in the performance-oriented comparison of wraps and their main competition, mutual funds.

Less than 5 percent of our clients say they want to beat the stock market, he says. Very few of our clients want that roller-coaster ride.

Despite the controversy, the wrap industry is growing fast, a testament to either good service or effective marketing.

In 1986, four years after E.F. Hutton started the first wrap program, less than $5 billion was invested in wraps, according to Thomas Kostigen, publisher of The Wrap Fee Advisor, an industry newsletter. He estimates wrap assets at $50 billion by the end of last year; other estimates range as high as $90 billion. That pales beside the trillion-dollar mutual-fund industry, but the fast growth of wraps has brokerage firms salivating for ways to expand the market.

To open a wrap account, the investor fills out a questionnaire on finances, investment goals and willingness to take risks. The brokerage firm uses the information to help him select from its list of participating financial managers.

The manager makes all the buy and sell decisions.

The investor gets a professionally managed, highly diversified portfolio which is individually managed to their needs and desires, says Alan M. Sislen, director of institutional and consulting services for Merrill Lynch.

Critics such as Aronson say the consulting has little value after the portfolio’s long-term strategy is established. After that, the investor doesn’t need consulting, and could get trading services more cheaply elsewhere, Aronson says.

Proponents, however, say a wrap account may involve a large number of trades. If an investor executed his or her own trades through a broker, commissions could well add up to more than the all-inclusive 3 percent wrap fee, they argue.

Most major firms require a minimum investment of $100,000 to set up a wrap account. But this threshold is gradually being lowered, with some programs that call themselves wraps requiring initial investments of $25,000 or less, as the industry tries to compete for the huge middle-class market that’s been pouring money into mutual funds.

The fee may be negotiable, and decline as the account gets bigger — to 2.5 percent a year for a $500,000 account, for example. The brokerage typically gets about two-thirds of the fee and the manager one-third.

Proponents say wrap-account managers have no reason to churn — to buy and sell investments unnecessarily — since their earnings are not based on trading commissions.

Brokerage firms like wrap accounts because they provide a predictable source of income at a time when commission rates on individual trades are declining, and when many traditional customers are defecting to discount brokerage houses and mutual funds.

Financial managers like them because the sponsoring brokerage firm handles all the administrative and marketing chores. Without that packaging, many

financial managers wouldn’t take on a customer with less than $1 million.

Proponents say wraps should be assessed on how well the manager fits with the customer’s individual needs rather than on how much money is earned. The best wrap programs allow the customer to talk directly with the portfolio manager to make adjustments to fit individual needs, such as taking or delaying profits for tax reasons, they say.

Performance is one thing, Sislen says. But how much risk the manager is taking to generate that performance is a very important dimension that we go into with the client.

Nevertheless, critics say it’s dangerous to shrug off the effect of the annual fee, especially now that investment returns are more modest than in the last few years.

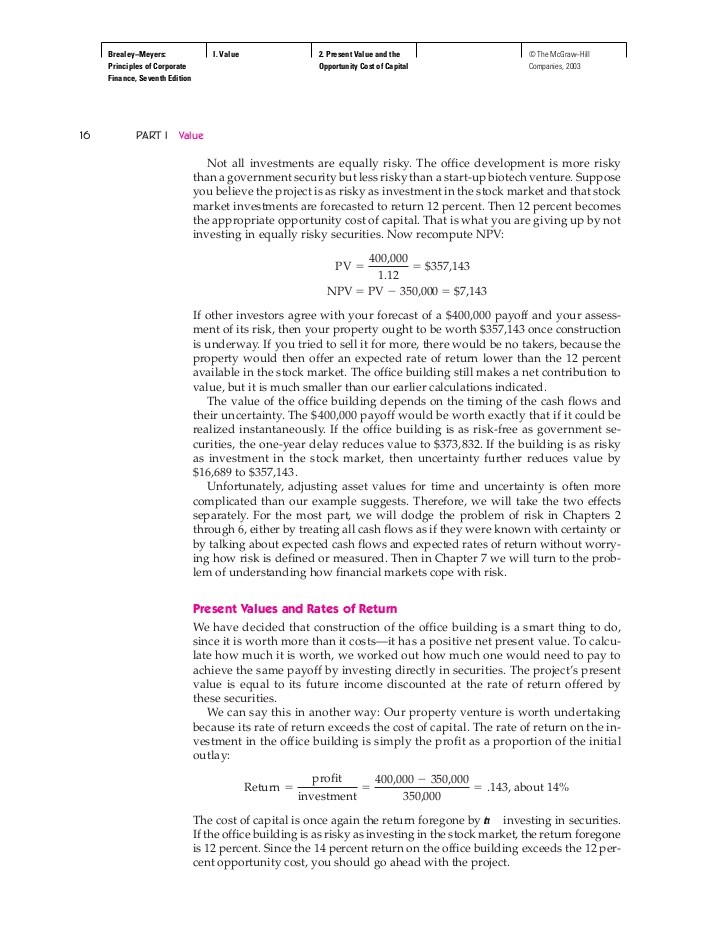

To use a simplified example, compare a $100,000 investment that earns 8 percent a year with one that earns 5 percent — a difference representing the 3 percent annual fee. Not accounting for taxes, after 10 years, the investment earning 8 percent is worth $215,892, while the 5 percent investment is worth only $162,889. The better return yields 32.5 percent more after 10 years.

Portfolio Management Consultants Inc. of Denver, a firm that evaluates portfolio managers and administers wrap programs, has studied the performance of more than 200 wrap managers. It found that over the last five years, wrap accounts investing in a wide variety of stocks earned a median 14.6 percent a year, while the Standard & Poor’s index of 500 stocks, a standard industry bench mark, did better: 15.6 percent a year. And the 14.6 percent wrap return represented performance before management fees were deducted.

The PMC study showed that other types of wraps also underperformed standard indexes conforming to their investment strategies.

Individuals can approach the return of the S&P 500 by investing in a mutual fund designed to mirror the index. Such funds typically charge much lower fees than wrap accounts.

Merrill Lynch’s Sislen says a comparison with these bench marks is inappropriate, because many conservative investors will accept lower performance in return for a decrease in their risk of losing money.

PMC president Ken Phillips, however, says the study does show how important it is for the customer to receive a thorough, honest and understandable quarterly report of how his or her wrap account is doing compared with these bench marks. A wrap, which he says can be a good choice for an affluent investor, may relieve the customer of day-to-day worries, but still demand continuing ongoing scrutiny.

It’s difficult for the investor to shop for a wrap account, because most firms won’t say upfront who their portfolio managers are or how they’ve done in the past.

Many of these programs don’t want to disclose (their performance) for publication, says Monica Parry, senior counsel for the SEC’s Division of Investment Management.

The only way to get this information is to go through the long initial consulting process, after which the brokers will reveal the identities and performances of their portfolio managers. With mutual funds, the same research could be accomplished in a half-hour with any of the many published performance summaries.

The Securities and Exchange Commission has been studying wraps for the last two years. Its findings probably will be issued this fall, says SEC Commissioner Richard Y. Roberts. The SEC is concerned about whether all programs truly offer comprehensive, individualized financial consulting, he said.

The staff of the commission is concerned that some wrap-fee programs are merely packaged as wrap-fee programs where, in fact, they are mutual funds with higher management fees, he said last week. As mutual funds, they would be subject to more stringent reporting requirements than wraps.

One of the problems, Phillips of Portfolio Management Consultants says, is that most customers are brought into wraps by their brokers, and brokers are accustomed to selling products, not providing continuing consulting services.

He says that of late, more programs have appeared that call themselves wraps, but that simply bundle some existing mutual funds into a package aimed at less-affluent investors.

As the minimum investment drops to $25,000 and lower, he says, it’s less and less likely customers are getting legitimate financial consulting.

His conclusion: Caveat emptor.