The risks of floating rate funds v s new Floating Rate Notes

Post on: 9 Май, 2015 No Comment

After watching interest rates rise up and loot the value of your bond fund last year, you might be looking for alternatives that won’t drop in value.

Good luck. New Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen wants to continue the central bank’s policy of letting long-term interest rates increase slowly. And when interest rates go up, bond values go down.

The finance industry gladly offers options to insulate, or hedge, you from such increases. One that attracted a lot of money last year from retail investors: Floating-rate funds. They hold securities whose interest payments adjust with changes in interest rates.

But there’s more risk drifting around those funds than one might suspect. We’ll explore some of them so you aren’t disappointed if you choose to dive in.

A safer, brand-new option comes from the U.S. Treasury in the form of a Floating Rate Note. It, too, adjusts along with changes in interest rates short-term rates, that is.

Treasury’s FRNs are not very practical for common investors like you and me. And the Fed has indicated it plans to leave short-term interest rates alone for a while, so their paltry yields will likely remain paltry for a while.

FLOATING RATE FUNDS

Floating-rate funds invest mainly in bank loans, also known as senior loans, leveraged loans, floating-rate loans or adjustable-rate loans. Corporations issue such loans, or bonds, to raise money. Often, the companies already have a lot of debt and are challenged when it comes to raising money through traditional means. They are essentially below-investment-grade bonds. Some of them are just plain junk.

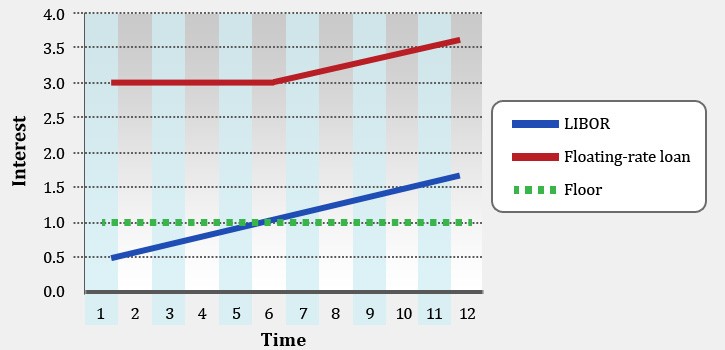

These loans usually have a fixed rate, or spread, and a second rate that resets periodically with changes in benchmark interest rates. It might be the Prime Rate, used by U.S. banks to loan to businesses, or LIBOR. the London Interbank Offered Rate.

Floating-rate funds were born amid the topsy-turvy rates of the 1970s, according to Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. But they caught investors’ fancy again last year.

From January 2013 through last month, $71 billion flowed into 54 floating-rate mutual funds and exchange traded funds, nearly doubling their total assets.

It’s obvious why. Last year, Bank Loan funds averaged a 5.68 percent gain before taxes, according to Morningstar. They’ve gained 4 percent a year over the past decade. (They’ve lost money, on average, so far in 2014.)

Let’s look at the largest of the lot: Oppenheimer Senior Floating Rate Fund (Ticker: OOSAX ). It more than doubled in size last year to $20 billion in assets. Morningstar rates it four out of five stars. Returns since its founding in 1999 have exceeded 5 percent a year.

Read the prospectus, however, and you’ll see why these things are riskier than typical bond funds.

Their returns most closely behave like the returns of high-yield bonds, or junk bonds. Their one-year default rate (1.6 percent as of January) is about three times as high as the typical U.S. bond (0.6 percent), according to Moody’s Investors Service.

As a result, their returns are more volatile. A $10,000 investment in the fund’s Class A shares in June 2007 would’ve fallen below $6,900 in value December 2008, according to Morningstar. It’d be worth nearly $13,350 today.

But the same investment in a total bond index fund or ETF tracking the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, a measure of the entire domestic bond market, would be worth just more than $14,000. And it would not have lost value in 2008.

The Fund is not designed for investors needing an assured level of current income, says the fund’s prospectus. It also warns against using it as a short-term trading vehicle.

Look what else the fund’s prospectus says. It can leverage up to one-third of its assets, meaning it can borrow against its loans to boost returns. It can also buy derivatives, which derive their value from other things. Derivatives are what got Oppenheimer’s Core Bond Fund (once held by the Oregon College Savings Plan) in trouble.

Some senior loans aren’t as easily bought or sold as stocks, as many fund managers learned in 2008, when the bank loan market locked up. And not all loan rates adjust as frequently as interest rates do, meaning there can be a lag in their yields when rates increase slowly. Both of these tendencies complicate life for fund managers.

Know that taxes have shaved about 2 percentage points off returns, according to Morningstar, so they should be held in a tax-sheltered account.

Floating-rate funds are expensive, too. They’re mostly available in share classes that charge a load, or commission, at purchase. On average, they charge $150 for every $10,000 investment, according to Morningstar. An index fund might charge $10 or $15 for the same investment.

Other alternatives: the passively managed iShares Floating Rate Bond ETF (Ticker: FLOT ) or the SPDR Barclays Investment Grade Floating Rate ETF (FLRN ). They cost only $15 to $20 per $10,000 (FLRN is the lower of the two). They track the Barclays US Floating Rate Note < 5 Years Index of less-risky, corporate-issued bonds. Morningstar classifies them as ultra-short bond funds. The three-year-old ETFs returned between 0.73 and 0.76 percent last year, beating other short-term bond indexes.

Actively managed floating-rate funds might be good for someone with a large stake in bond funds who wants to smooth future volatility.

But there are other ways to accomplish the same thing. Increasing your short-term bond or short-term Treasury fund holdings would better smooth the ups and downs of your bond portfolio, according to research by The Vanguard Group. which peddles both types of short-term funds (but not floating-rate funds). You can also use a Stable Value Fund in your 401(k) in place of a short-term bond fund.

FLOATING RATE NOTES

FRNs are the first new security introduced by the government since its successful Treasury Inflation Protected Securities debuted in 1997. TIPS, you’ll recall. adjust their payout based on changes in the Consumer Price Index, a measure of inflation.

Treasury’s Floating Rate Notes don’t have credit risk because nothing is considered as safe as a loan to the U.S. Treasury.

They are similar to ultra-safe Treasury bills because their adjustable index rate is tied to the 13-week T-bill. The T-bill’s set rate, or spread, is determined when it’s first auctioned. That happens each week, so a FRN’s index rate resets weekly, too.

They currently come in two-years terms and pay interest every three months. Investors can buy them for as little as $100 on TreasuryDirect.gov. They can also sell them on the open market before the two-year term is up.

This will enable investors to get the interest on T-bills — admittedly not much right now — without having to reinvest the maturity every three months, said Marc Fovinci, fixed-income strategy and portfolio manager at Ferguson Wellman Capital Management in Portland. They should be a nearly risk-free way for investors to earn some interest on cash that’s not needed immediately.

Treasury auctioned $15 billion of 2-year FRNs Jan. 31 to great demand. Investors sought nearly six times as much as the government had to offer.

That demand meant the government could set a low spread on the note only 0.045 percent. Add to that the index rate of 0.055 percent and investors initially got only 0.1 percent return on the note. A two-year treasury note auction the same day paid yielded 0.38 percent paltry, but significantly higher.

It’s a great product for short-term money managers, said Keene Satchwell, who head’s Becker Capital Management ‘s fixed-income team in Portland. It’s probably not a great product for individuals.

Indeed, of the $15 billion in notes issued, only $15 million went to buyers on TreasuryDirect, which are mostly individuals.

As designed, the FRN’s rate already has changed. Twice. Last week’s 13-week bill auctioned at 0.095 percent, which boosted the Floating Rate Note’s yield to 0.14 percent. A $10,000 FRN investment earned about 4 cents a day last week instead of 2.5 cents a day right after the auction. You can see what I mean looking at the note’s daily index online .

The only time you’d buy (Floating Rate Notes) is if you’re extremely bearish on interest rates and you want to shelter money from an upcoming storm, Satchwell said. You’re giving up a lot of potential income for that safety.

I’ll stick to buying inflation-adjusted U.S. I Savings Bonds. currently yielding 1.38 percent, or 10-year TIPS at auction and hold them to maturity (here’s why ). I’m more concerned about protecting my long-term savings from price inflation. Plus, I can get better rates (0.75 to 0.85 percent) on my emergency savings in high-yield savings accounts at CapitalOne360 or FNBO Direct. with even less hassle and federal insurance of up to $250,000.

Float that around for thought.

- Brent Hunsberger is an Investment Adviser Representative in Portland. For important disclosures and information about Brent, visit ORne.ws/aboutbrent . Reach him at 503-683-3098 or itsonlymoneyblog@gmail.com .