The pros and cons of donoradvised funds

Post on: 16 Август, 2015 No Comment

‘Tis the season for giving, and charities are ramping up their appeals with mailers, email appeals and more. The challenge for donors is finding the most effective way to give.

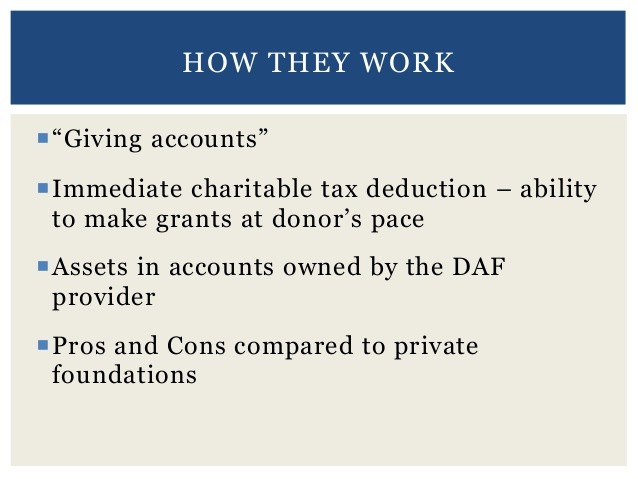

One of the hottest methods for giving right now is through donor-advised funds, funds that donors create by depositing cash, appreciated securities or other assets, and then distributing the money to charities over time. Contributions to donor-advised funds grew 23.5 percent, or $17.3 billion, in 2013, bringing their assets to $53.7 billion, according to the National Philanthropic Trust. That growth handily outpaced all other giving vehicles, like private foundations and charitable trusts, as well as the 4.4 percent growth in overall giving. Contributions to donor-advised funds now represent 7 percent of all individual charitable donations.

One reason for their appeal: Individuals can take an immediate tax deduction against the full amount they contribute to a donor-advised fund, but there are no rules or regulations about how quickly the money actually has to be distributed. Why wouldn’t a donor like donor-advised funds? They’re the best thing in the world for donors, said Ray D. Madoff, a professor at Boston College Law School and an expert on trusts and estates.

But t he rapid growth in contributions to donor-advised funds has not been matched by grants to charities from those funds. At $9.66 billion, grants increased 12.6 percent — hardly shabby, but only slightly more than half the growth rate of the contributions coming into donor-advised funds.

That’s the part the charities find difficult, the fact that there is no payout requirement, said Stacy Palmer, editor of The Chronicle of Philanthropy.

Catherine Lane | iStock | Getty Images Plus

Community foundations run a number of these funds, but financial services companies such as Fidelity, Vanguard and Schwab have some of the biggest. The Chronicle of Philanthropy actually ranks Fidelity Charitable, launched by Fidelity Investments in 1992, as the second-largest charity, not far behind United Way.

The financial firms are adept at taking in non-cash assets, such as shares of stock, which have appreciated.

The donor-advised funds have gotten very good at helping you essentially turn those assets into cash, Palmer said. That’s something that if you went down to your local homeless shelter, they would have no idea how to do that.

Kim Laughton, president of Schwab Charitable, said the ease of donating non-cash assets encourages people to give more generously to charity than they might otherwise because they get the benefit of a hefty tax deduction without a lot of hassle.

The chances of people distributing two shares of Apple stock to their 10 favorite charities are pretty low, she said. They are more likely to pull out their checkbook or credit card and have less capacity to give. When donor-advised funds offer an easy way to donate appreciated stock, the charities are getting more than they would have, she added.

But critics charge that companies offering these funds also manage to profit from them, in the form of fees assessed on the donor-advised fund accounts. Fidelity charges donors 0.6 percent of the first $500,000 in a donor-advised fund account, for example, and donors with assets invested in mutual funds also pay the fees associated with those funds.

Fees associated with the accounts vary. Laughton said Schwab clients’ donor-advised fund assets are in either very low-cost, no-load funds or best-in-class performers in their various asset classes. She added that Schwab Charitable’s assets represent 0.27 percent of Schwab’s total assets, and that t he amount of investment Schwab has made in Schwab Charitable far exceeds any revenue they would have generated.

In virtually all the donor-advised funds, though, it is hard for investors to get information on all the fees involved, said Madoff.

Just as there are hidden fees in the 401(k) world, there are all these hidden fees here too, she said, so b y the time a donor distributes money to a charity from a donor-advised fund, some assets inevitably will have been chipped away by all those fees. Donors giving directly to a charitable foundation would not face that erosion.

The biggest criticism of donor-advised funds, though, is that they serve as financial holding pens for the assets of people who want to grab a tax deduction but have no immediate plans for any actual charitable giving. The overall distribution rate from donor-advised funds in 2013 was 21.5 percent, down from a high of 24.7 percent in 2010. That’s well above the 5 percent distribution required of foundations, but assets in foundations increased just 5.7 percent, compared with 19.8 percent for donor-advised funds.

Some people using donor-advised funds actually may be using them in lieu of creating foundations. The National Philanthropic Trust puts the average account size in donor-advised funds at $247,217.

Laughton said Schwab has accounts as small as $5,000 and as large as $800 million, but the median account size is just over $20,000, and the median distribution rate is well above the national average. These clients, she said, treat the accounts much more like a checkbook.

But clearly, if the national distribution rate is 21.5 percent, many others are less active. Donors may feel charitable because they are putting money into these funds, but the charitable impact is nil unless they grant the money to nonprofits.

Madoff argues that the rise of donor-advised funds may have actually cannibalized traditional charitable giving. The rate of Americans’ charitable giving has remained constant, at roughly 2 percent of GDP, for several decades. But donations to donor-advised funds now account for about 5 percent of overall giving. And since less money is getting to charities than is going into the donor-advised funds, the effect on the rate of overall giving is negative.

Still, if recent years are any indication, more and more Americans will be donating not directly to the local soup kitchen but to donor-advised funds, said Palmer, the editor of the Chronicle of Philanthropy. Millions of baby boomers will be retiring, selling family businesses, or passing away, setting in motion an enormous transfer of wealth to the next generation, and she expects donor-advised funds to reap the benefits as recipients of the money ponder what to do with their charity plans.