The Incredible Shrinking Alpha

Post on: 2 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

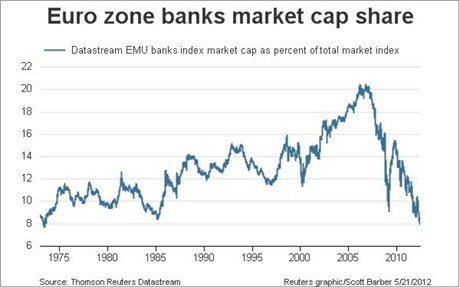

The pool of victims active managers need to exploitthe sheep that are to be shearedis shrinking. Unless youre Warren Buffett, the winning strategy is to not play.

Advertisement

In his famous 1991 paper, The Arithmetic of Active Management, Nobel Prize winner William Sharpe explained that before costs active management is a zero-sum game, and after costs it is a negative-sum game. He writes: Properly measured, the average actively managed dollar must underperform the average passively managed dollar, net of costs. Empirical analyses that appear to refute this principle are guilty of improper measurement. In other words, for active managers to be successful they must have victims that they can exploit. Who exactly are these victims?

The evidence is that the victims are likely to be individual investors. The research has found that, in aggregate, individual investors around the globe underperform standard benchmarks, such as low-cost index funds, even before costs or taxes. When they trade, they are exploited by institutional investors. And while there is a wide dispersion of results among individual investors, even the best traders have a hard time covering costs. Interestingly, research by Brad Barber and Terrance Odean has found that not all underperformance can be attributed to the excessive trading done by individual investors. On average, individual investors exhibit perverse security-selection abilitiesthey buy stocks that go on to earn sub-par returns and sell stocks that go on to earn above-average returns.

20book_0.jpg /%Since alpha is a zero-sum game, if there are losers, even before costs, there must be winners. Who are the winners? The winners are institutional investors, such as actively managed mutual funds. The research shows that on a gross-return basis, active fund managers are able to generate alpha, exploiting the bad behavior of individual investors. For example, Jonathan Berk and Jules van Binsbergen, authors of the 2013 study Measuring Skill in the Mutual Fund Industry, found that the average mutual fund has added value by extracting about $2 million per year from financial markets, and that the value added is persistent for as long as 10 years. Berk and van Binsbergen concluded, It is hard to reconcile their findings with anything other than the existence of money management skill.

The 2000 study, Mutual Fund Performance: An Empirical Decomposition into Stock-Picking Talent, Style, Transactions Costs, and Expenses by Russ Wermers, provides further evidence of stock-picking skill. Wermers found that on a risk-adjusted basis, the stocks that active managers selected outperformed their benchmarks by 0.7 percent per year. However, investors earn net, not gross, returns. The research finds that their total expensesnot just the funds expense ratio, but trading costs as wellmore than eroded the benefits derived from their stock-selection skills, leaving investors with net negative alphas. What economists call the economic rent is going to the scarce resource (the ability to generate alpha), not to the plentiful resource (investor capital). That occurs just as economic theory predicts it should. But while active institutional investors have been able to exploit the bad behavior of individual investors, the fund sponsors have been the winners, not investors in the funds.