The Big Picture Active versus passive investing

Post on: 9 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

The debate over active versus passive investing strategies has been part of the academic landscape for decades.

Generally, the passive investing argument holds that the market is efficient and cannot be beaten consistently. On the other hand, the active investing argument maintains that the market is not perfectly efficient and these inefficiencies can be exploited for the benefit of investors. More recently, the flood of financial and economic news, coupled with an increased desire to act on that information, has caused the number of non-professional market participants to grow. This has heightened the collective emotional state, contributing to the creation and bursting of market bubbles and causing incorrect pricing, which is believed to make financial markets less efficient. While the active/passive debate continues to draw adherents, other economic theories are poised to fill the academic void. More importantly, practical evidence shows that taking advantage of professional advice and being an active investor can help to avoid the risks, unexpected costs and increased downside exposure that, in the real world, are part of the passive approach.

What is the difference between active and passive investing?

Despite what would seem to be a straightforward concept on the surface, considerable confusion appears to exist as to what constitutes passive and active investing. According to Nobel laureate William F. Sharpe, in the end, it is actually quite simple:

“Of course, certain definitions of the key terms are necessary. First a market must be selected – the stocks in the S&P 500, for example. Then each investor who holds securities from the market must be classified as either active or passive. A passive investor always holds every security from the market, with each represented in the same manner as in the market. Thus, if security X represents 3% of the value of the securities in the market, a passive investor’s portfolio will have 3% of its value invested in X. Equivalently, a passive manager will hold the same percentage of the total outstanding amount of each security in the market. An active investor is one who is not passive.” 1

Succinctly, the passive investor invests in the market (as represented above by the S&P 500 Index) so as to exactly match the index weights. The active investor does something other than that, making an active judgment that the index weights are, somehow, less than ideal. Part of the problem that investors appear to face is a surprising abundance of different definitions of “passive” and “active.” The ever-popular Wikipedia defines it as: “Passive management (also called passive investing) is a financial strategy in which an investor (or a fund manager) invests in accordance with a pre-determined strategy that doesnt entail any forecasting (e.g. any use of market timing or stock picking would not qualify as passive management). The idea is to minimize investing fees and to avoid the adverse consequences of failing to correctly anticipate the future. The most popular method is to mimic the performance of an externally specified index.” Another popular website, Investopedia, defines it as: “An investment strategy involving limited ongoing buying and selling actions. Passive investors will purchase investments with the intention of long-term appreciation and limited maintenance.” These definitions appear to link passive investing with benign laziness. However, an investment manager who simply bought only shares in Nortel Networks or Lehman Brothers and stood pat would hardly represent any sort of passive benchmark. At the same time, mimicking the shifting weightings of each stock within a 500- stock index on a daily basis may not require any actual thought or research, but it would certainly require some steady, ongoing trading activity. In the face of this confusion, the real reason to use the Sharpe definition (a serious proponent of passive investing himself) is straightforward. In the end, it boils down to the research. All of the academic research based on assessing the success or failure of active investment management stems from comparison of these same active managers with their passive benchmark (invariably an index). Using any other definition would nullify the actual research done in this arena.

ETFs and index funds

One of the reasons that the passive versus active debate has remained an artifact of academia is that real, living investors cannot be truly passive. No index is available for purchase. However, along with the dramatic increase in the flow of financial and market information and improvements in technology, investors have recently seen a proliferation in exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Not surprisingly, proponents of passive investing have cheered the arrival of the index-based ETFs. In theory, these ETFs offer an inexpensive and efficient way to invest in the desired index, thus making them ideal for passive investors. Unfortunately, it is not quite that simple. Even index-based ETFs are not identical to the index. Before delving into ETFs, investors also need to be aware of specific high-risk aspects of some of these investments, such as the use of leverage and synthetic exposures. Even with the plain vanilla versions, there are costs and risks associated with ETFs that are not part of the index. Investors face transaction costs and commissions whether they are making an initial or periodic purchase or simply rebalancing their portfolio. As with any other exchange-traded security, the investor will also have to cover the cost of the bid/offer spread. Additionally, the market may discount the value of an ETF that holds specific illiquid securities, producing a pricing differential. Investors also bear the risk that the ETF may be closed. In 2012, 11 Canadian ETFs were terminated 2. However, for the passive investor the largest issue will likely be Tracking Error. Since index weightings change every day, index-based ETFs can experience difficulty keeping up with these changes or face challenges matching the index outright. For example, the Dow Jones Emerging Markets Total Stock Market Specialty Index has 3,264 constituents 3. The BMO Emerging Markets Equity Index ETF, which is designed to replicate this index, has 283 holdings 4. Needless to say, matching the exact moves of a larger index can be a significant challenge. Add in the various costs, and on a return basis ETFs generally will underperform their target index under all market conditions, as illustrated in the example below.

Index funds are similar to ETFs in many ways. The obvious difference is that index funds do not trade on an exchange and they cannot be bought and sold throughout the day. The price of an index fund is based on net asset value (NAV) and for an ETF it is based on the market quote (where the bid/offer spread must also be deducted). While the costs of ownership are different, as with mutual funds, there are costs associated with index funds. Typically, the management expense ratio of an index fund is less than 1%. Also, while there are choices of index funds in the Canadian market, they have not seen the same level of proliferation witnessed in the EFT universe.

However, as illustrated by the index funds below, they generally experienced the same consistent under performance.Another challenge of passive investing that investors may fail to consider is the nature of their actual portfolio. Most indexes are market-capitalization weighted (based upon the number of shares outstanding times the share price). This means that larger companies have more of an effect on the index than smaller companies. The result is that indexes display momentum. A stock that did well yesterday has a bigger market cap today, and accordingly accounts for a greater proportion of the index. This forces the ETFs or index funds to then buy more of that stock, which can potentially drive up demand and the price even further in the process. In other words, index investors are increasing their allocation to recent winners and reducing their exposure to stocks that have underperformed. They are in effect executing a sell low and buy high strategy.

In addition, while one could reasonably argue that the S&P 500 Index may represent a well-balanced and diversified U.S. portfolio, other national and regional indexes may not be so well balanced. Domestically, the S&P/TSX Composite Index is often criticized for its very high weightings in financial, materials and energy stocks. Examining this proportional breakdown of an investment in the index may reveal levels of investment concentration that would not be appropriate for many investors. The volatility of gold prices since the beginning of 2013 has been a bitter reminder of this risk for those following the Canadian market index.

In theory

The main pillar supporting the idea of a passive investing style has been the notion that markets are efficient. That is, the market price of stocks, bonds or other securities reflect all of the available information about the underlying issuers. Any effort, time and money spent attempting to determine something that the market does not already know is simply wasted. While the roots of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) stretch back to the late 1800s, the University of Chicago’s Eugene Fama and Paul Samuelson are widely regarded as the individuals responsible for the development of EMH during the early 1960s. Subsequently, the theory came into question as empirical studies revealed that substantial and lasting inefficiencies, such as the out performance of value stocks (those with high book-to-market ratios), existed within the market 5 .

More recently, EMH has become less favoured in the wake of the booms and busts of the tech bubble of the late 1990s and the 2008-2009 market melt-down. Investor behaviour has since become a greater focus of attention. Current realities, which would not have been anticipated in the 1960s, have come into play. Individual access to real-time market information over a mobile device has not turned everyone into an efficient investor. Even Fama has conceded that poorly informed investors could theoretically lead the market astray and that the prices of securities could become somewhat irrational as a result 6. One can easily picture the “theoretical” purchasers of asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) in 2007 as being “poorly informed” with respect to the toxic mortgages to which these securities were exposed. Further, it is not much of a stretch to say that the credit rating agencies, whether “poorly informed” or not, helped support “somewhat irrational” prices for these securities for an extended period of time before they plummeted in value.

More vocal critics of EMH, such as Paul Volcker, former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, have subsequently chimed in, saying “it should be clear that among the causes of the recent financial crisis was an unjustified faith in rational expectations, market efficiencies, and the techniques of modern finance.” 7 More bluntly, financial journalist Roger Lowenstein stated that “the upside of the current Great Recession is that it could drive a stake through the heart of the academic nostrum known as the efficient-market hypothesis.” 8 Just as Newton’s physical “laws” were replaced by Einstein’s relativity, in the end, it appears likely that the active/passive argument will fade and the academic research pertaining to behavioural finance will supplant it.

Actively managed funds

Not surprisingly, investors’ experience with the markets during 2008-2009 raised their sensitivity to both downside protection and volatility. Fortunately, through portfolio managers, investors can take advantage of a number of approaches to active investing. For example, investment styles such as “value” and “growth,” as well as quantitative modelling and technical analysis, are used by active portfolio managers. As a benefit, active investors can benefit from downside protection. Active managers can avoid the blind selling of assets that typically accompanies a bear market. By the same token, they can avoid jumping on the bandwagon when a “hot” stock starts to take off, fuelling an irrational buying frenzy.

Source: Globe HYSales 9

As the table illustrates, the average Canadian equity fund has outperformed the index in all of the recent bear markets. The Canadian equity funds data is not just illustrative of top-quartile performers, but is an average of hundreds of funds. While no one would be happy with an average decline of 25.6% over these bear market episodes, the 6.7% material cushion provides measurable protection during the most challenging times. Active management also helps reduce portfolio volatility, as shown in the table below. Volatility is measured here in terms of standard deviation.

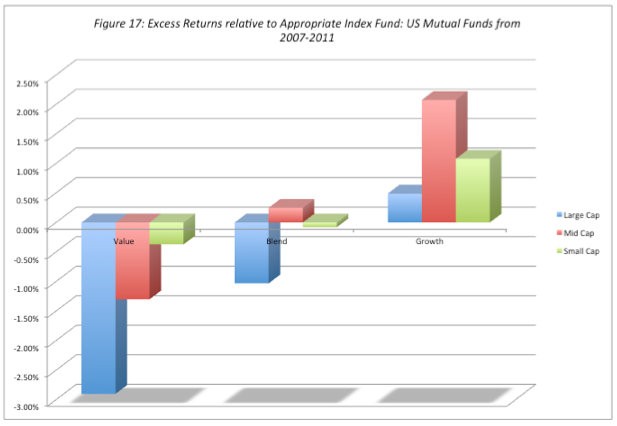

In addition to avoiding risky portfolio weightings during frothy markets, active managers can also add value during periods where markets are strengthening, as illustrated in the graph below. According to a recent study by Russell Investments, 76% of Canadian institutional large-cap managers beat the benchmark in 2012 while the average large-cap manager produced a return of 9.4% in 2012. 10 This was 2.2% ahead of the S&P/TSX Composite Index’s return of 7.2%. Over longer periods of boom and bust in the market, active management pays off but is more the purview of the best managers. “The median manager return over the last 10 years was in line with the benchmark return, but the top-quartile manager was roughly 135 basis points ahead on average per quarter. On average, more than 51% of large-cap managers have beaten the benchmark over the last 10 years.” 11 These results suggest what would make sense intuitively. The median active manager can provide benchmark returns over longer periods such as 10 years. However, top-quartile managers can provide excess returns of 1.35% per quarter.

Conclusions

- While the debate continues, support for the efficient market hypothesis and passive investing have been hard-hit in the wake of the recent financial crisis. Other theories and models will ultimately take their place as inefficient pricing behaviour continues to haunt financial markets.

- In the end, while investors keen on index investing can get close to the passive ideal, they will also fall short of the benchmark. Active investment strategies have provided investors with better downside protection, less volatility and a real opportunity to outperform something they can’t actually invest in – an index.

- The mindset of the do-it-yourself investor is most likely to align with passive investing. Investors who are more likely to be proponents of active investing are also more likely to value professional advice and service when establishing a long-term financial plan.

The United Private Client Managed Portfolios and Evolution Private Managed Accounts provides managed portfolio solutions to Assante Wealth Management’s high net worth clients across Canada. My association with Assante Wealth Management gives me access to these portfolio solutions managed by some of Canada’s top investment managers. The above commentary was provided by Richard J. Wylie, CFA, Vice-President, Investment Strategy at Assante Wealth Management.