The Best Investment Strategy Getting Out of Our Own Way

Post on: 28 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

We’re still making the same old mistake of buying investments when prices are high and selling them once their prices have fallen.

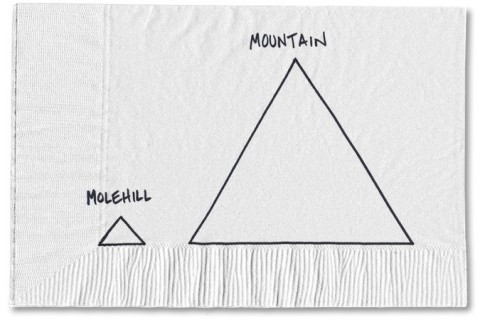

I had hoped things had changed, I really did. But Morningstar’s latest Investor Returns data says otherwise. More than 10 years after I first started thinking about this data, the behavior gap still exists. The behavior gap is what I refer to as the difference between what the average investment returned and what the average investor earned.

What’s the difference? Pretend for a minute that we have a mutual fund with a 10-year-average return of 10 percent per year. That’s the investment return. If you put your money in the fund, kept it there for the entire 10 years, and didn’t add or take out any money, then your investor return would also be 10 percent. So in this very hypothetical example, the investment return and the investor return were the same.

The problem is that few people invest this way. Who would buy a long-term investment and actually hold on to it for the long term? That would be silly!

Most people buy and sell. We hunt for the next rock star mutual fund manager and follow our brother-in-law’s tips at the family barbecue. In fact, as Nate Silver points out in his book “The Signal and the Noise,” the hold times for stocks have declined every decade until the 2000s. Today, we hold our stock investments for about six months. We’re clearly not what anyone would think of as long-term investors.

It’s easy to understand why we behave this way. We’re hard-wired to get more of those things that give us pleasure or security, and to run away from things that cause us pain. That trait has kept us alive over thousands of years, but it makes us terrible investors. When we follow our natural instincts, we end up buying things after they’ve gone up. Then, when they go down, which they always do at some point, we sell.

The weird thing is that we do all this believing we’re protecting our families’ futures. But this well-intentioned behavior has a cost. As Morningstar’s data shows, the average equity mutual fund in the United States had a 10-year average return at the end of 2013 of 8.18 percent. The average investor only earned 6.52 percent. That’s a difference of 1.66 percentage points. It may seem like a small number, but it makes a big difference when you think of it in terms of dollars.

Imagine 10 years ago that you put $100,000 in an average American equity mutual fund. If you just sat there, you’d have $219,517 in your account at the end of 10 years. But because we’re human, you more likely only earned the 6.52 percent return of $188,066. That equals losing more than $30,000, a 17 percent difference.

The numbers are even more depressing in other investment types. Balanced mutual funds are designed to help us manage our behavior by including both stocks and bonds. They provide a cushion in down markets in exchange for not hitting it out of the park on the way up. It seems like that would help us behave. Well, the average balanced fund returned 6.93 percent, but the average investor only managed 4.81 percent.

It’s critical to understand that none of this is the investment’s fault. The average investment did its thing, but our behavior determines what we actually get. What makes this so frustrating is that we’re talking about an average American equity fund, not the best one, just the average. In other words, all we had to do to improve our return by over 1.5 percentage points was pick a mediocre (by definition, average) equity fund and then just sit there.

That’s it.

Instead, we ran around reading the latest research, watching CNBC and looking for the best fund because that’s the American way. Why settle for average when you’ve got a shot at being among the small minority that can pick out a stock or a mutual fund that will beat the market?

The past is the past, and there’s nothing we can do about it now. But here’s the key: The next 10 years start today. If the past is any indication of the future, we need to do something different if we want a different result. The hard part of investing isn’t picking the best investment. Instead, it’s sticking with the one we’ve picked. Only then will we have a shot at closing the behavior gap over the next 10 years.

The best part about this is that once you design a portfolio, the only thing you have to do is nothing, aside from some occasional rebalancing when some investments rise and others fall. It reminds me of my favorite Warren Buffett quote: “Benign neglect, bordering on sloth, remains the hallmark of our investment process.” As he’s demonstrated more than once, investing is one place where we are rewarded for being lazy.

Carl Richards is a financial planner in Park City, Utah, and is the director of investor education at the BAM Alliance. His book, “The Behavior Gap ,” was published in 2012. His sketches are archived on the Your Money page.