Signal and Noise

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

You can’t make what you can’t measure because you don’t know when you’ve got it made.

Dr. Irving Gardner

We’ve traveled far, and learned much along the way. We waded through all these details in search of an eat watch: a way to know, day in and day out, how much to eat to achieve any weight goal we choose. And now we know exactly what an eat watch must do, if not yet how to make one.

In The Rubber Bag chapter we learned how the human body gains and loses weight: by eating too many or too few calories compared to what it burns. Further, we discovered that for most of us, adjusting the amount we eatwhat goes into the rubber bagis the only practical way to control our weight. Therefore, an eat watch must be able to measure the balance of what goes in and what gets burned: to calculate whether we’re getting enough, too little, or too much food.

In the Food and Feedback chapter we learned why some people constantly gain weight, while others maintain a constant weight, and still others seem trapped on a rollercoaster of gain and loss. It became clear that the mechanism, if not the cause, of most weight problems is a lack of negative feedback: a failure to adjust, by appetite, the amount eaten to the amount burned. The eat watch must then provide feedback. in a manner that will stabilise the system: allow you to achieve and maintain your desired weight.

The eat watch began as a mythical device, a miracle cure beyond reach. But along the way we’ve collected enough information about the body and about feedback to design something that does the job.

Wired science

By pulling together what we know about the eat watch, the rubber bag, and feedback, we can draw a wiring diagram for an eat watch, even though we may not yet know how to build some of the components.

We start with the simplified rubber bag view of the body. We’ve installed meters to measure the rate at which calories go in and get burned. The readings from these meters, which vary as the creature inside the rubber bag awakes from a deep sleep, drinks a cup of coffee with two teaspoons of sugar, then runs to catch the bus, are fed to integratorsboxes that add up calories over a period of time, say 24 hours, and report the total. The totals are sent to a comparison unit that subtracts the calories burned from calories eaten. The result of this is precisely what we’re looking for: the calorie shortfall (if negative) or excess (if positive) that determines whether the rubber bag burns off fat or packs it on. The indicator on the eat watch says Eat! whenever the balance is negative and goes out when it’s positive.

As long as you only eat when the Eat! indicator is lit, you’ll never gain weight. If you’d like to lose some weight, simply adjust the indicator so it comes on only when the sum is negative by more than some number of calories. Suppose you want to take off 10 pounds over two months. Just work out the total calories you have to burn by multiplying the pounds you wish to lose by the calories in a pound of fat, 10 Ч 3500 = 35000, divide by the number of days in two months, 35000 / 60 585, and set the Eat! light to come on when the result is less than 585. To put on 2 pounds in 30 days, adjust it to say Eat! whenever the difference is +233 ((2 Ч 3500) / 30) or less.

With an eat watch helping to balance the nutritional books on a constant basis, you’ll never err very far in the direction of too many calories. Consequently, you’ll never have to atone by cutting your calorie intake way back. In other words, once you’re done peeling off your extra weight, you’ll never be hungry again, as long as you rely on the eat watch.

The calorie counting catch

Let us repair to the workshop and try to turn this back of the envelope sketch into hardware. Rummaging through the parts bin, we quickly find all the components at the top of the diagram. Integrators, comparators, and indicators are available for pennies apiece.

We come up short, however, looking for those confounded meters that read calories in and out. It’s possible to measure these quantities, at least in principle. If you were crazy enough to do so, you could calculate calories in by looking up everything you ate, as you ate it, in a calorie counting book and punching in the numbers on a keyboard. You could track calories burned by measuring body temperature, blood sugar, heart and respiration rates, etc. especially if you were willing to calibrate the readings for your own body over a month. Biosensors that measure these quantities have been used on astronauts, athletes, and intensive care patients for years.

But the whole idea of the eat watch is to be unobtrusive and not disrupt your life! Being slim and trim and the envy of your peers loses a lot of its gloss if it means spending the rest of your life wired up like a labrat. Bend over, please, this won’t take but a moment.

No.

But it could be done. This is encouraging.

Cause and effect

Let us stand up straight, step back from the yawning chasm of the absurd, shrug off the bioharness, and ponder whether there might be a better way of going about this. Perhaps the linkage between cause (calories eaten and burned) and effect (weight gained and lost) could be used to accomplish the same results without ending up as a cyberpunk centerfold.

After all, what we care about is weight. not calories. Might there be a way to extract the information we need from the weight numbers served up so easily by the scale? Indeed there is, but extracting the information we seek, calorie balance, from the confusing welter of weight measurements requires another mathematical trick borrowed, not from engineering but from the toolbox of the stock and commodity trader.

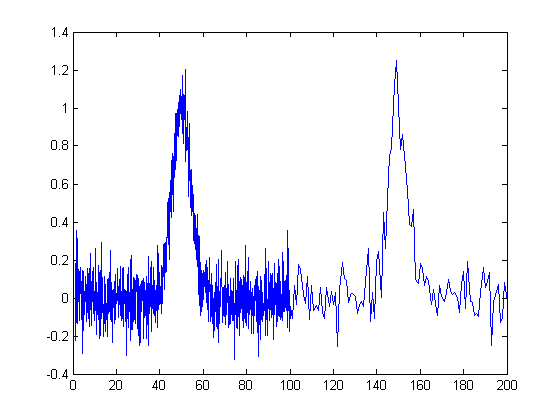

Like most attempts to characterise a complicated system by a single number, a scale throws away a great deal of the subtlety. Every morning the rubber bag sloshes over to the scale and heaves itself onto the treads with a resounding splorp. The scale responds with a number that means something or other. If only we knew what. Over time, certainly, the scale will measure the cumulative effect of too much or too little food. But from day to day, the scale gives results that seem contradictory and confusing. We must seek the meaning hidden among the numbers and learn to sift the wisdom from the weight.

Dexter’s diet

On July 1, Dexter went on a diet, resolute in his intention to shed 10 pounds before Labour Day. Every morning Dexter weighed himself and wrote the number on a piece of paper. Every evening, he plotted his weight on a graph and wrote any comments that came to mind in his Diet Diary. Let’s relive those two months of Dexter’s life by peeking at the records he kept.

Dexter’s diary

Here I go, and this time I’m going to succeed. I’d betterI’ve told everybody at the office I’m going on a diet, and if I don’t slim down this time they’ll rib me all the way ’till Christmas. So, farewell indulgence, hello Dexter’s Slimming Summer.

All right! One day, almost half a pound! I’m already ahead of schedule. At this rate.

Woe is me. Last night I got up, went into the pantry, and just looked at the popcorn jar. That’s all. And today I woke up three pounds heavier than when I started to diet. My stomach is growling, my soul is bruised, and my weight is up. Good night.

Some glorious Fourth. Well, at least the porkometer is down from yesterday. But it would be amusing if I could get back below where I started this diet, wouldn’t it?

Oh frabjous day, the diet is finally kicking in. Four pounds less, more than two below where I started! I shall not conclude the onion ring I swiped from yon Cassius at dinner had anything to do with it. Onward!

Stuck on this pesky plateau. Still, I guess it’s better to be stuck below where I started than spiraling upward toward Chandrasekhar’s limit.

One measly bowl of sauerkraut at bedtime, for the sake of Almighty Bob! I mean, every diet book says that stuff has fewer calories than sawdust, but boom!here I am, almost two weeks into this cruel torture ritual, still two pounds above where I started. If it weren’t so late and I weren’t so tired I’d go make a double scoop sundae and chuck this damnable diet.

Well, that’s interesting. Yesterday must have been a blip. Either that, or maybe panic and depression is what really causes me to lose weight.

Gosh, has it been three weeks? Well, not very interesting weeks, anyway. The occasional new low, but basically I’m stuck in an up and down cycle that’s running about a week long. Maybe my body has adapted to this diet and I’ll go on being hungry forever and never lose another pound. There’s a cheerful thought.

Maybe there’s justice in the universe after all. One hundred and forty-three poundsI’ve done it! Now, if I just stay here this diet is history!