Performance evaluation and selfdesignated benchmark indexes in the mutual fund industry

Post on: 18 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Berk A. Sensoy*

First Draft: August, 2005

This Draft: January, 2006

Job Market Paper

Abstract

I use a new database of self-designated mutual fund benchmark indexes to explore the principal-agent

relationship between fund investors and fund companies. Performance relative to the benchmark affects a

fund’s inflow of new investment, even controlling for other performance measures. The flow-

performance relations give funds an incentive to deviate from the benchmark. Consistent with this

incentive, 42% of funds deviate on size and value/growth such that their benchmarks are less

representative of their portfolios than plausible alternatives. Tracking error is greater among funds with

stronger incentives to deviate. In contrast with previous work on mutual fund tournaments, funds do not

alter risk-taking relative to the benchmark in response to midyear benchmark-adjusted performance. This

fact is consistent with plausible parametric estimates of the flow-performance relations, which suggest no

incentive to do so. I relate the results to relative performance evaluation theory and discuss the

implications for optimal contracting in the fund industry.

* University of Chicago Graduate School of Business. I am very grateful to my dissertation committee members

Steve Kaplan (chair), Eugene Fama, Toby Moskowitz, and Josh Rauh for their guidance and support. I thank Ola

Bengtsson, Raife Giovinazzo, Mark Klebanov, Lubos Pastor, Francisco Perez-Gonzalez, Morten Sorensen, Amir

Sufi, and seminar participants at the University of Chicago for helpful comments; Don Phillips and Annette Larson

of Morningstar, Inc. for providing data; and Eugene Fama and Ken French for making their factor portfolio data

available. I also thank the Fischer Black fellowship fund for financial support. Comments are welcome; please

address correspondence to Berk Sensoy, bsensoy@chicagogsb.edu.

Page 2

Introduction

Mutual funds have incentives to increase their inflows of new investment because they receive a

percentage of assets under management as a fee.1 At the same time, investors in actively managed funds

presumably want the fund to maximize risk-adjusted returns2. To the extent that these goals diverge,

there is potential for agency problems, which are likely to be economically important because of the size

of the fund industry. According to the Investment Company Institute 2005 factbook, U.S. equity mutual

funds had total net assets of $4.4 trillion at the end of 2004.

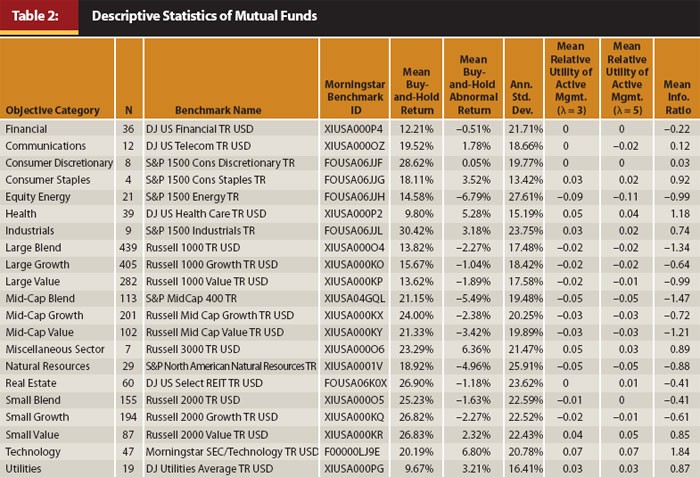

This paper uses a new database of self-designated mutual fund benchmark indexes to provide

evidence on the principal-agent relationship between fund investors and fund companies. The benchmark

data are available as a result of the 1998 SEC requirement that fund prospectuses present historical fund

returns alongside those of a benchmark index. The intent of the requirement is to provide investors with a

relevant comparison index, but the SEC does not regulate which benchmark is used. In practice, funds

typically use S&P or Russell indexes that are defined on size and value/growth dimensions, such as the

S&P 500 or the Russell 2000 Growth Index (an index of small cap growth companies).

I begin by investigating whether fund investors evaluate funds based on performance relative to

the benchmark, as the SEC presumably believed they would. I find that they do. A fund’s inflow of new

investment is positively related to its prior-year benchmark-adjusted return, even controlling for other

performance measures. This fact means that benchmarks are relevant to the agency relationship between

fund investors and fund companies. The marginal relation between flows and benchmark-adjusted return

constitutes an implicit incentive scheme, specifically an implicit relative performance evaluation contract.

As with any performance evaluation contract, the agent (funds) can be expected to respond to the

incentives it provides.

1 Basak, Pavlova, and Shapiro (2003) emphasize the importance of this incentive with a quotation from Mark Hurley

of Goldman Sachs: “The real business of money management is not managing money, it is getting money to

manage.” (The Wall Street Journal, 11/16/95.)

2 That the goal of investors is to maximize risk-adjusted return is consistent with the prevailing view of optimal

performance evaluation in the fund industry. This view holds that active managers should be rewarded for skill, not

exposure to systematic risk factors (or characteristics) associated with average returns. The logic is that there is no

reason an active manager should earn economic rents for achieving a risk/return profile that could be duplicated by

combining index funds.

Page 3

I then explore this contract. Specifically, I provide evidence on funds’ incentives for investment

behavior relative to their benchmarks, and show that fund behavior is consistent with those incentives. I

also consider the consequences for fund investors and for the funds themselves. The analysis sheds light

on two aspects of relative performance evaluation theory: “reference-group gaming” and tournaments.

The results also have implications for optimal contracting in the fund industry, and provide novel

evidence on mutual fund consumer behavior, the use of benchmarks in the fund industry, the cross-

section of fund risk-taking relative to the benchmark, and the performance consequences thereof.

To learn about incentives, I examine the shape of the relation between flows and benchmark-

adjusted returns, and find that it is not uniform across benchmarks. For funds with value/growth-neutral

benchmarks other than the S&P 500 (and for the overall sample), the relation is convex and

approximately quadratic, while funds whose benchmark is the S&P 500 or is value/growth specific face a

flatter, approximately linear relation.3 Convexity means that tracking error (the standard deviation of

benchmark-adjusted return) is implicitly rewarded – for a given expected benchmark-adjusted return,

higher tracking error increases expected flows at the margin. Therefore, while the positive relation

between flows and benchmark-adjusted return provides both groups of funds the incentive to beat their

benchmarks, and thereby the incentive to hold portfolios that differ from the benchmark, this incentive is

relatively stronger for funds with value/growth neutral benchmarks other than the S&P 500.4

Behavior is consistent with these incentives. Substantial fractions of funds hold portfolios that

differ significantly from their benchmarks on benchmark beta, size, value/growth, and momentum

dimensions. In fact, 42% of funds differ on size and value/growth to such an extent that their benchmarks

are “questionable”. Specifically, alternative S&P or Russell size and value/growth-based benchmarks

both better match the funds’ investment styles and are more correlated with their returns. Among these

3 The flatter relation for funds with value/growth specific benchmarks, which explicitly claim to be specialized, is

consistent with them having a greater appeal among more sophisticated investors who are less likely to chase

returns. Del Guercio and Tkac (2002) make a similar argument to explain the flatter flow-performance relation for

pension funds compared to mutual funds.

4 The idea that explicit incentive fees, as opposed to the implicit incentives considered here, might induce

investment in strategies that have a high variance around a benchmark is the topic of work by Das and Sundaram

(2002), Carpenter (2000), Cuoco and Kaniel (1998), and Elton, Gruber, and Blake (2003).

Page 4

funds, the average excess return R-squared with the actual benchmark is 69.7%, versus 83.3% with the

alternative benchmark. Consistent with their stronger incentive to deviate, tracking error is greater among

funds with value/growth neutral benchmarks other than the S&P 500.

Among funds with questionable benchmarks, there is no significant relation between benchmark-

adjusted return and Fama-French (1992) 3-factor alpha when controlling for the other performance

measures used in the flow regressions. So, from a contracting perspective, assuming that investors want

funds to maximize risk-adjusted returns (and want to “pay for skill”), for which I use alpha as a proxy,

they should not direct flows in response to questionable-benchmark-adjusted return (when controlling for

those other performance measures), simply because doing so distorts fund incentives to maximize alpha.

Yet investors do precisely that. This fact suggests a breakdown of optimal contracting in the fund

industry, and adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that fund investors are naïve when directing

flows (Del Guercio and Tkac 2002, Cooper, Gulen, and Rao 2005).

Ironically, then, by directing flows in response to performance relative to the benchmark in the

manner they do, investors provide incentives for funds to behave in such a way that benchmark-adjusted

return is not marginally informative of alpha, and a large fraction of funds do so. This behavior

represents an agency conflict given that i) at the margin, investors direct flows in response to benchmark-

adjusted return (even if they are naïve to do so), and ii) investors want to direct flows in response to alpha,

and therefore want the benchmark to contain marginal information about alpha.

The conflict comes with costs. Funds with questionable benchmarks induce distortions to an

investor ranking funds based on yearly benchmark-adjusted return. For example, in only 21.7% of

benchmark-years is the top-ranked fund using each fund’s actual benchmark the same as the top-ranked

fund that obtains pretending that funds with questionable benchmarks are actually benchmarked to their

alternative, more representative benchmarks. Moreover, though funds with questionable benchmarks take

significantly more risks relative to the benchmark, they do not earn higher benchmark-adjusted returns.

From the perspective of relative performance evaluation theory, having a questionable benchmark

is related to “reference-group gaming”, which occurs when an agent chooses a reference group other than

Page 5

the one desired by the principal.5 Because in practice benchmark changes are rare and because it is not

clear whether the fund manager or the fund board of directors set the benchmark in the first place, the

mapping to reference-group gaming is not indisputable. The mapping is on firmer ground if one expands

the concept of reference-group gaming somewhat, so that it includes ex post behavior that makes the

reference group, chosen ex ante, not the one preferred by the principal.

The analysis so far speaks to fund incentives and behavior in a static, on average sense. It is also

possible that, in their quest to increase flows, funds might have the incentive to manipulate their risk-

taking relative to the benchmark dynamically. This idea stems from the tournament aspect of relative

performance evaluation theory.6 In particular, tournament theory suggests that nonlinear payoff structures

may induce a relation between realized performance during an evaluation period and investment decisions

in the remainder of the period. Brown, Harlow, and Starks (1996) apply tournament theory to the mutual

fund industry, arguing that midyear losers have the incentive to increase their return standard deviation in

the second half of the year more than midyear winners. Chevalier and Ellison (1997) estimate the relation

between flows and prior-year market-adjusted return semi-parametrically, and find that it offers funds

incentives to alter the standard deviation of market-adjusted return in the 4th quarter of the year as a

function of market-adjusted return in the first 3 quarters. Both papers find evidence that supports their

arguments.

In light of these earlier studies, I investigate whether there is a relation between a fund’s change

in tracking error (the standard deviation of benchmark-adjusted return) from the first half of the year to

the second and its benchmark-adjusted return in the first half of the year.7 I find no relation. This result

is consistent with the relations between flows and benchmark-adjusted return if, as the data cannot reject,

5 Reference-group gaming is one of four ways, described by Gibbons and Murphy (1990), in which distorted

incentives might manifest themselves if the agent can influence the output of the reference group. In specific

applications, Carmichael (1988) argues that non-tenured faculty have the incentive to recruit inferior colleagues, and

Dye (1992) argues that paying top executives based on performance relative to their industry provides incentives to

operate in industries with inept rivals.

6 The theory of tournaments is developed by, among others, Lazear and Rosen (1983), Nalebuff and Stiglitz (1983),

Green and Stokey (1983), and Rosen (1986).

7 I focus on changes from one half of the year to the next because of data availability. In my sample period, funds

are only required to report their holdings semiannually, and most do so at the end of June and December.