Passive vs active investing

Post on: 9 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Warren Ingram tells us why he backs passive investing.

Warren Ingram* | @Moneyweb  | 9 September 2009 08:17

One of the great debates in the investing world is around the benefits of active vs index (or passive) investing. Many large international institutions make use of indexing for some or all of their investments whilst retail index funds have a massive following in the rest of the world. In South Africa, index investing has started taking off with ETF providers like Satrix capturing significant market share. For private investors, index investing can offer significant benefits but there are still strong arguments in favour of active managers too.

WHAT IS ACTIVE INVESTING?

As is usual in the investment world, there is some jargon to decipher before one can make sense of the debate around this issue. Firstly, the term active investing refers to managers who try to choose specific investments that will beat a specific benchmark. To keep it simple, we will focus on shares, so an active manager is one who tries to select a number of different shares in an attempt to generate better growth than the stock market. An index investor simply tries to replicate the index performance i.e. tries not to take more or less risk than the stock market.

COSTS AND TURNOVER MAKE A BIG DIFFERENCE

One of the undoubted advantages of index investing is the benefits of lower costs. The average active fund has an annual cost of 1.5% 2% per year whilst an index ETF only costs 0.5% per year. That means an active fund manager has to generate an additional 1% per year just to keep pace with an index ETF. The other cost of active management is the amount of turnover of shares in a portfolio during the year. Every time an active fund manager buys or sells a share, the fund incurs another cost in addition to the annual management fees. Some active managers change an entire portfolio every year ie, 100% turnover. John Bogle (the father of index investing) found that the average active fund investor in the USA, only received 47% of the cumulative returns generated by the active fund due to the turnover costs. By comparison, an index fund investor received 87% of the cumulative return. This means that an American investor who placed $10,000 in an average active fund for 16 years would have earned $49 000 whilst the index investor would have earned $90 000. The statistics in South Africa are bound to show similar results. On the issue of costs there is a clear argument in favour of index funds. Active managers would argue that they are worth the higher fees due to their performance.

WHICH IS BETTER?

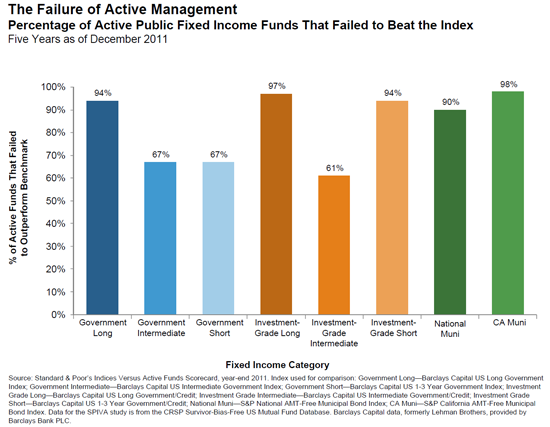

There is no simple answer to this question. Statistically not many active managers are able to beat the stock market over a long period, however some do beat the market very handsomely over extended periods of time. The difficulty for private investors is the selection of those managers that are able to beat the market. Unfortunately, past performance REALLY is no indicator of future returns.

According to MotleyFool.Com, only 20% of large mutual funds actually manage to beat the US stock market (S&P 500) over longer periods of time. For a private investor, the odds are certainly against you if you have an 80% chance of choosing the wrong managers! Fortunate investors who do choose the successful managers benefit from fantastic returns. According to the Morningstar unit trust figures to the end of July, the best general equity unit trust generated a return of 23.31% per year for the last ten years. This is almost double the return of the All Share Index which grew by 13.07% per year for the last ten years. Even with the additional management fees and turnover costs, the top unit trust was a great investment.

Unfortunately, we cannot simply choose the top performing fund in the hope that it will beat the market over the next ten years. History tells us that top performing unit trusts often underperform in future which makes fund selecting very difficult indeed. One of the big reasons for this underperformance is that the funds become victims of their own success. They become too large and unwieldy and eventually start to mirror the market, but they still carry the higher costs of an active manager and therefore underperform the market. In South Africa some of the very best managers are having this problem as their funds are so large that they can only buy the 40 or 50 largest companies on the JSE. A solution for them would be to limit new investors but they continue to keep their funds open. This decision will compromise their performance over time.

SOME SOLUTIONS

Many of the large pension funds in the USA use a combination of index investing and active investing. For example, the largest pension fund in the USA, the CalPERS Fund has 69% of its domestic share exposure invested in indexes. The balance is invested with active managers who attempt to beat the market. South African investors can adopt this approach, called core and satellite, if they buy index ETFs via a stock broker and select some individual shares. Alternatively they can select an index unit trust and one or two active unit trusts to complement the index fund. This is a useful solution and is worth consideration.

Alternatively, you can simply buy the index via a unit trust or ETF. History tells us that you have a great chance of beating 80% of all unit trusts over time. If you have the interest and time, you can research the fund managers in SA who have the skill and ability to beat the market. One mistake to avoid is to simply choose the top fund from last year. Many people do this and are regularly disappointed.

My final suggestion is that you can manage your own portfolio of shares in an attempt to beat the market. The odds of beating the market are stacked against you BUT you have some advantages over institutional investors. Firstly, you dont have to pay yourself so your fees will be lower. Secondly, you dont have to report your performance to investors (or the press) on a monthly basis. This allows you to take long term views on good value companies and give them the time to realise their value. Finally, you can buy some of the smaller companies on the JSE that are not available to large institutional funds. If a large fund of R17bn buys a company it will need to account for at least 1% of the portfolio in order to add to performance of the fund. If the company only accounts for 0.2% of the fund and it doubles in value it will only add 0.2% to the fund! This means the fund needs to allocate a minimum of R170m to each company. Unfortunately many of the smaller companies on the JSE are worth less than R170m in total! This gives the private investor a great advantage as some of these smaller companies are great businesses and are trading at massive discounts to their net asset value.

*Warren Ingram, CFP, has been advising people about their money management since 1996. He is a director of Galileo Capital, www.galileocapital.co.za