Money Managers Battle High Frequency Traders With New IEX Platform

Post on: 19 Май, 2015 No Comment

Related Content

Mutual fund managers are fighting back against high frequency trading firms, which they claim hurt long-term shareholders by jumping in and out of markets and raising trading costs. Their weapon: New York–based IEX Group. the first alternative trading system owned by the buy side. An electronic-trading team from Royal Bank of Canada started IEX, which launched in October and caters to traditional investors. IEX is owned by a group of mutual funds, hedge funds. family offices and employees. San Diego–based Brandes Investment Partners and Capital Group, based in Los Angeles, each hold stakes of less than 5 percent to comply with rules governing mutual funds.

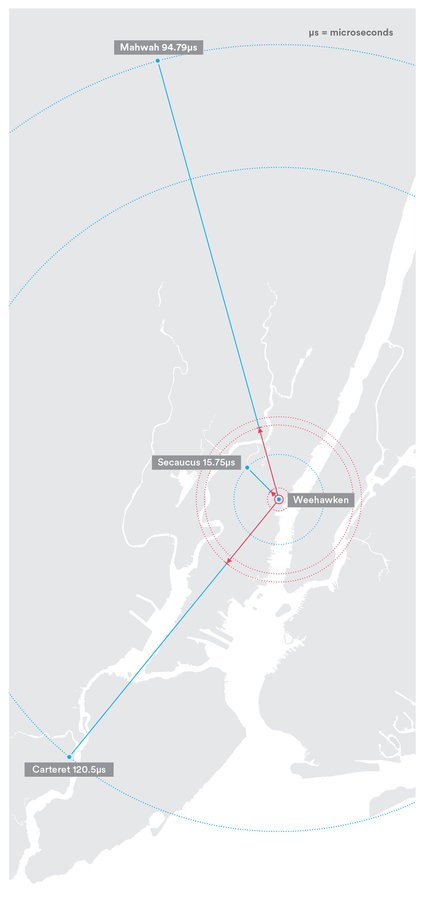

Regulatory changes from the 1990s and 2000s, designed to increase competition and make the market fairer for mainstream investors, have fragmented the trading of U.S. equities. Trading now takes place on dozens of exchanges, broker-dealer trading systems, electronic communications networks and dark pools, where buyers and sellers are matched anonymously. Amid this fragmentation and automation, high frequency traders use computer algorithms to buy and sell securities at blazing speed, disadvantaging mutual funds and other investors that lack the same firepower.

Brad Katsuyama, president and CEO of IEX and former global head of electronic sales and trading at Toronto-based RBC Capital Markets, says RBCCM had built a smart order router, which determines the best transaction venue based on various preferences. The team saw an opportunity after realizing that money managers know little about how the markets handle and mishandle their trades. But RBC couldn’t serve traditional managers on the scale it wanted because it’s a broker-dealer and those clients want to split their business among many parties. Katsuyama and three other executives from his group left to form IEX and registered it as a market so that its clients are the brokers themselves. “We decided to go to the root of the problem,” he says. “Exchanges and dark pools are catering to the highest-volume participants, which are the high frequency traders.”

“Rather than talk about it, the team from IEX actually took action,” says Joseph Scafidi, director of trading at $25 billion Brandes. As of late November, IEX hadn’t released any volume numbers, but Scafidi is happy. “We are executing more volume with less impact than with other ATSs or even the exchanges,” he says. “We have also seen data shared by other buy-side clients that indicate they are having similar experiences.”

IEX differentiates itself by charging buyers and sellers a flat fee. The more volume it can attract, the more profit it makes. Flat-fee pricing also avoids the conventional rebate, or maker-taker, system, whereby a market gives a broker or liquidity provider a rebate while charging another broker or liquidity taker a fee. That system creates an incentive for a broker to route trades for rebates rather than to get the client the best possible execution. Other IEX features aim to protect investors by fending off high frequency interlopers: Where some rival platforms offer a slew of special complex orders to draw speedy traders, it has just four simple order types.

CEO Katsuyama thinks IEX’s biggest contribution could be raising the bar on best-execution rules. Brokers are supposed to ensure that clients’ trades are handled fairly, but ATSs don’t have to disclose how their markets work or which order types they offer — and until IEX, none did. The firm has made public its Form ATS, which details its operations for the Securities and Exchange Commission. Besides opening the door to feedback from critics and supporters, this voluntary disclosure may prompt other venues to follow suit. “If the buy side starts asking for documentation before it sends its next order, it changes the way the market works,” Katsuyama says.

Sal Arnuk, co-head of trading at Chatham, New Jersey–based brokerage Themis Trading, which uses IEX, believes the new ATS is doing something unique. “The SEC has proposed regulating dark pools since 2009, but wouldn’t it be great if dark pools voluntarily publicized all the mechanics of how they work, including order types and average trade size?” Arnuk says. “Dark pools will always say, ‘All customers need to do is ask us.’ But that’s not true disclosure.” • •