Invest FAQ Mutual Funds Fees and Expenses

Post on: 13 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Last-Revised: 28 Jun 1997

Contributed-By: Chris Lott (contact me )

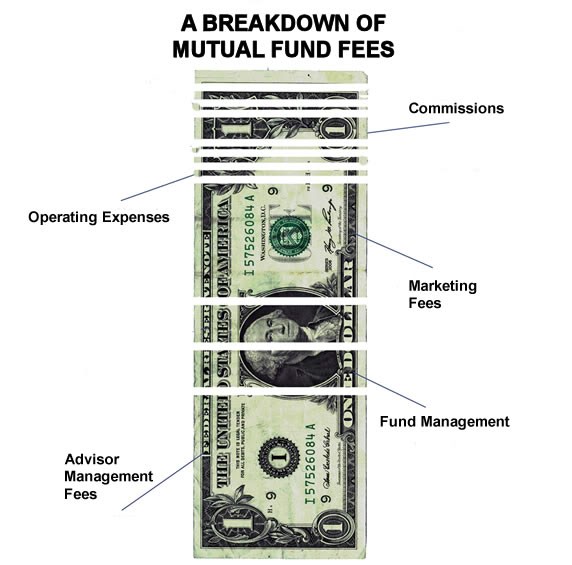

Investors who put money into a mutual fund gain the benefits of a professional investment management company. Like any professional, using an investment manager results in some costs. These costs are recovered from a mutual fund’s investors either through sales charges or operation expenses.

Sales charges for an open-end mutual fund include front-end loads and back-end loads (redemption fees). A front-end load is a fee paid by an investor when purchasing shares in the mutual fund, and is expressed as a percentage of the amount to be invested. These loads may be 0% (for a no-load fund), around 2% (for a so-called low-load fund), or as high as 8% (ouch). A back-end load (or redemption fee) is paid by an investor when selling shares in the mutual fund. Unlike front-end loads, a back-end load may be a flat fee, or it may be expressed as a sliding scale. A sliding-scale means that the redemption fee is high if the investor sells shares within the first year of buying them, but declines to little or nothing after 3, 4, or 5 years. A sliding-scale fee is usually implemented to discourage investors from switching rapidly among funds. Loads are used to pay the sales force. The only good thing about sales charges is that investors only pay them once.

A closed-end mutual fund is traded like a common stock, so investors must pay commissions to purchase shares in the fund. An article

elsewhere in this FAQ about discount brokers offers information about minimizing commissions.

To keep the dollars rolling in over the years, investment management companies may impose fees for operating expenses. The total fee load charged annually is usually reported as the expense ratio. All annual fees are charged against the net value of an investment. Operating expenses include the fund manager’s salary and bonuses (management fees), keeping the books and mailing statements every month (accounting fees), legal fees, etc. The total expense ratio ranges from 0% to as much as 2% annually. Of course, 0% is a fiction; the investment company is simply trying to make their returns look especially good by charging no fees for some period of time. According to SEC rules, operating expenses may also include marketing expenses. Fees charged to investors that cover marketing expenses are called 12b-1 Plan fees. Obviously an investor pays fees to cover operating expenses for as long as he or she owns shares in the fund. Operating fees are usually calculated and accrued on a daily basis, and will be deducted from the account on a regular basis, probably monthly.

Other expenses that may apply to an investment in a mutual fund include account maintenance fees, exchange (switching) fees, and transaction fees. An investor who has a small amount in a mutual fund, maybe under $2500, may be forced to pay an annual account maintenance fee. An exchange or switching fee refers to any fee paid by an investor when switching money within one investment management company from one of the company’s mutual funds to another mutual fund with that company. Finally, a transaction fee is a lot like a sales charge, but it goes to the fund rather than to the sales force (as if that made paying this fee any less painful).

The best available way to compare fees for different funds, or different classes of shares within the same fund, is to look at the prospectus of a fund. Near the front, there is a chart comparing expenses for each class assuming a 5% return on a $1,000 investment. The prospectus for Franklin Mutual Shares, for example, shows that B investors (they call it Class II) pay less in expenses with a holding period of less than 5 years, but A investors (Class I) come out ahead if they hold for longer than 5 years.

In closing, investors and prospective investors should examine the fee structure of mutual funds closely. These fees will diminish returns over time. Also, it’s important to note that the traditional price/quality curve doesn’t seem to hold quite as well for mutual funds as it does for consumer goods. I mean, if you’re in the market for a good suit, you know about what you have to pay to get something that meets your expectations. But when investing in a mutual fund, you could pay a huge sales charge and stiff operating expenses, and in return be rewarded with negative returns. Of course, you could also get lucky and buy the next hot fund right before it explodes. Caveat emptor.