Institutional Trading Information Production and Corporate SpinOffs

Post on: 24 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Thomas J. Chemmanur*

Boston College

Shan He**

Louisiana State University

August 2008

* Professor of Finance, Fulton Hall 330, Carroll School of Management, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467.

Phone: 617-552-3980. Fax: 617-552-0431. E-mail: chemmanu@bc.edu.

** Assistant Professor of Finance, Patrick F. Taylor Hall 2158, E.J. Ourso School of Business, Louisiana State

University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803. Phone: 225-578-6335. Fax: 225-578-6366. E-mail: shanhe@lsu.edu.

We would like to thank the Millstein Center for Co rporate Governance and Performance, Yale Univ ersity, for

research support. For helpful comments and discussions, we thank Yawen Jiao, Debarshi Nandy, Gang Hu, Mark

Liu, Wayne F erson, a nd Jef f Po ntiff. We al so t hank s eminar part icipants at B oston C ollege, L ouisiana St ate

University, Un iversity o f New Hampshire, Florid a St ate Un iversity, an d con ference p articipants at th e First

Singapore International C onference on Fi nance at t he National U niversity of Si ngapore, t he Shareholders an d

Corporate Governance Conference at Oxford University, the 2008 China International Conference in Finance at

Dalian, the AsianFA-NFA 2008 international conference at Yokohama, and the FM A annual meetings for helpful

comments. We thank the Abel/Noser Corporation for providing us with their institutional trading data, and Judy

Maiorca for answering many data related questions. We remain responsible for all errors and omissions

Page 2

Institutional Trading, Information Production, and Corporate Spin-offs

Abstract

Using a large sam ple of proprietary transaction-level institutional trading dat a, we em pirically

analyze, for the first time in the literature, the role of institutional investors in corporate spin-offs. In the

first part of t he paper, we study the im balance in post-spin-off institutional tra ding between parent and

subsidiary, and analyze this imbalance to test three different hypotheses regarding institutional investors’

role in spin-offs: information prod uction, pure pla y, and risk management. In the second part of the

paper, we ex amine the information production role of institutional inv estors in detail by analyzing the

predictability of institutional trading around corporate spin-offs for the short-term and the long-term stock

returns following spin-of fs. In the thi rd part of th e paper, we study the pat tern and profitabilit y of

institutional trading following spin-offs. Our empirical results can be summarized as follows. First, there

is significant i mbalance i n post-spin-off institutiona l trading between parent s and subsidiaries; this

imbalance increases corresponding t o the differ

characterizing the two entities, beta risk, and long-t erm growth prospects. Second, institutional trading in

the combined firm two months prior to the spin-off has significant predictive power for the announcement

effect of a sp in-off. Third, institutional trading in the subsidiary immediately after spin-off co mpletion

also has predictive power for its subsequent long-term stock returns; this predictive power is greater when

the subsidiary’s size constitutes only a smaller fraction of the combined firm’s size. Fourth, the predictive

power of institutional trading is weaker for the parent firm’s long-term returns; further, unlike in the case

of the subsidiary. institutional invest ors start expl oiting t heir private infor mation after the spin-off

announcement, but before the spin-off is com pleted. Finally, institutional investors are able to realize

superior profits by trading in the equity of the subsidiary in the first quarter after the spin-off. While our

results provi de some support for all three hypothe ses re garding the role of institutional i nvestors in

corporate spin-offs, they provide particularly strong support for the information production hypothesis.

JEL classification: G32, G34, G14

Keywords: Corporate Spin-offs, Instit utional investors, Institutional trading, Inform ation production.

ence in the extent of inform ation asy mmetry

Page 3

Institutional Trading, Information Production, and Corporate Spin-offs

1. Introduction

In the last fe w years, there has been a considerable increase in c orporate spin-off activity. This

increase in spin-offs has been partly attributed to institutional investors’ preferences, and their pressure on

firm managers to undertake spin-offs.1 Both the academic and pract itioner literature has conjectured that

breaking up a conglomerate into “pure play” companies may benefit institutional investors such as mutual

funds in several way s, while sim ultaneously resulting in an increase in the share price of the firm

conducting the spin-off. For example, in a recent theoretical paper, Chemmanur and Liu (2005) show that,

in a setting with asymmetric information between firm insiders and outsiders re garding the firm ’s true

value, an undervalued firm can improve its stock price through a spin-off. The basic idea in their paper is

that a spin-off can increase inform ation production by institutional investors about the firm. so that, in

equilibrium, firm insiders with favorable private information (i.e. with severely undervalued equity) will

choose to conduct a spin- off, increasing their firm ’s share price. However, there has been no em pirical

research on the role of institutional in vestors in corporate spin-offs. The objective of this paper is to fill

this gap in the literature b y analyzing empirically the role of institutional investors in spin-offs, making

use of a large sample of transaction-level institutional trading data, for the first time in the literature.2

Institutional investors may play three different roles around corporate spin-offs, as suggested b y

the academic and practitioner-oriented literature on spin -offs. The first possible role is the “i nformation

production” role (Chemmanur and Li u (2005)), which suggests that a spin-off can increase information

1 For example, the important role played by institutional investors in corporate spin-offs is reflected in the following

quote from an article in the Financial Times (October 28, 2005) that attributes the recent breakups of conglomerates

to a shift in investor preference: “But a new backlash against conglomerates suggests a more lasting shift in investor

preferences may be taking place — driven in part by the growing influence of hedge funds and private equity houses.

In pub lic m arkets, big has rarely ap peared less b eautiful. In the US, the m ost visi ble sign is the break-up of

companies such as Cendant, the sprawling leisure group behind Avis rental cars and the Orbitz travel website, which

this week announced a four-way demerger to try to lift its flagging share price. It follows a similar decision by Barry

Dillers InterActive Corporation to spin off its Expedia travel site and the breaking apart of Viacom, a media empire

that owns CBS television network, MTV and Paramount Pictures.”

2 There is a growing literature on the role of institutional investors around other corporate events: see, e.g. Parrino,

Sias, and Starks (2003), who study the role of institutional investors around forced CEO turnovers.

Page 4

production a bout t he ind ividual di visions of the f irm by i nstitutional in vestors, and th us helps th e

company to “unlock hidden value”.3 The second possi ble role of institutional investors in a s pin-off can

be thought of as “risk management”. The risk management role suggests that institutional investors can

manage their own risk better after a spin-off b y better allocat ing their invest ment acro ss stocks o f

different risk classes after a spin-off rather than leaving asset allocation to conglomerate fir ms.4 In other

words, a portfolio m anager desiring a high-risk po rtfolio can invest in the higher risk division of a

conglomerate firm after a spin-off, while another p ortfolio manager desiring a low-risk p ortfolio can

invest in the lower risk division; clearly, such fine-tuning of risk is not possible in the absen ce of a spin-

off. If such risk manage ment benefits are ind eed present, a spin-off may increase the de mand for the

firm’s equity from institutional investors, increasing st ock price. The third possible role of institutional

investors in a spin-off can be referred as “pure play ”. The pure play role sugg ests that spi n-offs allow

institutions (e.g. mutual funds) to fine-t une their in vestments in a firm ’s equity according t o their own

fund investors’ preferences. For example, growth funds can invest in the high-growth divisions, and value

funds can invest in lower growth divisions (whi ch may gener ate more r eliable cash fl ows) of a

conglomerate firm after a spin-off. Since many U.S. mutual funds are marketed to investors as “growth

funds” or “value funds”, splitting conglomerates into pure play companies can make the shares of the

resulting firms more attractive to those funds, i ncreasing demand for these shares and consequentl y their

3 Many firms claim that the objective of their proposed spin-offs is to “unlock value”. For example, a recent article

in the Financial Times (October 25, 2005) commenting on Cendant’s spin-offs said: “Cendant’s planned split echoes

moves by other large conglomerates such as Viacom, the media group, to spin off units in order to ‘unlock value’ for

investors.”

4 Institutional investors’ preference to manage their own risk is also cited as a factor that led to the Cendant spin-off

as well as other recent spin-offs. To quote an article regarding the Cendant spin-off in the Financial Times (October

28, 2005): “Henry Silverman, chief executive of Cendant, argues that the rise of hedge funds has undermined one of

the greatest attractio ns of big diversified companies: their ability to manage risk and produce consistent earnings.

These most active of traders would rather allocate assets themselves than outsource the risk to com pany managers.

‘Investors dont want portfolios (from companies) any more,’ he says. Fund managers have long claimed they prefer

to allocate assets among sectors rather than leave it to conglomerates, but hedge funds take this to a new extreme by

actively seeking out volatility and risk in order to offset it ag ainst investments elsewhere. … Cendant — which had

been carefully constructed to balance risk across sectors and different stages of the economic cycle — says it came to

have more than half its sh ares held by hedge funds, leaving it li ttle choice but to give them the more focused

investment opportunities they crave.”

Page 5

price.5 The above three roles are clearly not mutually exclusive: institutional investors may perform all of

these roles ar ound corporate spin-offs. We will discu ss the three roles of institutional investors around

corporate spin-offs in more detail and develop testable hypotheses in section 2.

The objective of this paper is to develop an empirical analysis of the role of institutional investors

in corporate spin-offs, for t he first time in the literature. In particular, we make use of a large sam ple of

proprietary transaction-level institutional trading data to analy ze whether institutional invest ors perform

one or more of the three roles discussed above around corporate spin-offs. Further, we study the

information production role of institutional investors in more detail by study ing the information content,

pattern, and profitability of institutional trading around corporate sp in-offs. Our data include transactions

from January 1999 to December 2004 which were o riginated from 531 different institutions (with a total

annualized trading princi pal of $4. 61 trillion over all U.S. equities). There were altogether 66

conglomerates that had spin-offs dur ing this period. Our sam ple institutions engaged in about 16%, in

terms of dollar value, of t he CRSP reported trading volume in the shares of these spin-offs firms. With

this dataset, we are able to track institutional trading in the shares of these spin -off firms both before and

after spin-off co mpletion. For the post-spin-off subsidiaries, w e identify institutional trading int o two

categories, namely, institutional share allocation sales (i.e. selling of shares allocated to the i nstitutions’

account through the pr o-rata distribution in spin- offs) and institutional post-s pin-off secondary market

trading (i.e. buying and selling of shares in the spin-off firms by institutions in the secondary market after

the spin-offs). This allows us to analyze the trading pattern and pr ofitability for these two categories of

transactions separately.

The paper is organized into three parts. In the fi rst part of the paper, our obj ective is to stud y

whether the three roles of institutional investors di scussed abo ve indeed play a signific ant role in

corporate spin-offs. To achieve this, we analyze the post-spin-off institutional trading imbalance (i.e. the

5 For example, regarding the spin-off of Viacom from CBS, an article in The New York Times (December 26, 2005)

pointed out that “Viacom is to continue to build its portfolio of cable channels overseas…That strategy is aimed at

highlighting the fast-growing cable network business. Meanwhile, CBS is taking steps to make its stock more

attractive to value investors, those who seek reliable income and dividends rather than rapid growth.”

Page 6

relative difference in the direction and magnitude of an institution’s trading in the equity of the post-spin-

off parent and subsidiary arising from the same conglomerate firm). We analyze this trading imbalance to

test three dif ferent hypotheses regarding the inform ation production, pure pla y, and risk manage ment

roles of institutional investors in spin-offs. In the second part of the paper, we exam ine the information

production role of institutional investors in further detail by analyzing the predictive power of institutional

trading around corporate s pin-offs for the short-term stock return (announcement effect) and the l ong-

term stock return following spin-offs. In the third part of the paper, we study the pattern and profitability

of institutional trading in the spun-off subsidiaries following spin-offs, which will shed further light on

whether institutional investors are able to realize abnormal profits from any information advantage they

may have from corporate spin-offs.

Our paper documents a number of results on the role of institutional investors around corpor ate

spin-offs, for the first ti me in the literature. These can be summari zed as follows. Our first set of result s

deals with institutional trading im balance: we find a significant im balance in post-spin-off institutional

trading between parents and subsidiaries. Thus, in the first three months immediately following the spin-

off com pletion, o ver 46 % of the trading by insti tutions in po st-spin-off p arent-subsidiary pairs was

originated in opposite dir ections (buy versus sell). Even for trading in t he same direction, institutions

concentrated their trading heavily in one division (parent or subsidiary) rather than trading symmetrically

in both divisions (see figure 1). We inte rpret this significant trading imbalance as evidence that spin-offs

improve institutional investors’ trading welfare by relaxing a trading constraint existing prior to the spin-

off. Further, we find that this imbalance incr eases corresponding to t he difference in inform ation

asymmetry between the post-spin-off parent and subs idiary, i.e. instituti onal investors bought m ore

equity in the post-spin-off division facing a hi gher extent of i nformation asymmetry. We al so find that

this imbalance increases corresponding to the difference in beta risk between parent and subsidiary, i.e.

sample institutional in vestors bought more equit y in the post-spin-off division with hig her market risk.

Finally, we f ind that this trading imbalance is pos itively related to the differe nce in long-t erm growth

rates between parent and subsidiar y, as well as to th e difference in expected profitability between these

Page 7

two division s. Overall, the above results on institutional tradi ng im balance support t he notion that

institutional investors play an inform ation production, a risk m anagement, and a pure pla y role around

corporate spin-offs.

Our second set of results deals with the predictive power of institutional trading around corporate

spin-offs. First, institutional trading in the combined firm two months prior to the spin-off has significant

predictive power for the announcem ent effect of a spin-off. Second, institutional trading in the spun-off

subsidiary immediately after spin-off com pletion also has predictive power for its subsequent long-term

stock returns. This predic tive power i s greater wh en the subsi diary’s size constitutes onl y a sm aller

fraction of the combined (pre-spin-off) firm’s size (see figure 2). Third, institutional trading in the parent

firm also has predictive p ower for its subsequent long-term stock returns, b ut this predictive power is

weaker than in the case of a subsidiary. Overall, the above results indicate that institutional investors have

considerable private infor mation about firms undergoi ng spin-offs, and pro vide further su pport for the

information production role of institutional investors around spin-offs.

Our third set of results deals with the pattern and profitability of institutional trading in the

subsidiary firm’s equity after spin-off com pletion. We separate institutional post-spin-off trading in the

subsidiary in to two categories: pure post-spin-off trading (i .e. bu ying and selling of t he spun-off

subsidiary’s stock by inst itutions in the secondary market after the spin-off ) and institut ional share

allocation sales (i.e. sales of subsidiary shares obtained through the pro-rata distribution in spin-offs by

institutional investors).6 We document that institutional investors ar e able to realize superior profits b y

trading in the equity of the subsidiary in the secondary market during the first q uarter after the spin-off.

Further, institutional investors’ trading profit in the post-spin-off subsidiary declines over time, which

suggests that their inform ation advantage in spin-offs is mostly confined to the immediate post-spin-off

6 Given that the post-spin-off parent takes on the identity of the combined firm, it is difficult to cleanly identify the

point in time at which the parent shares were acquired by institutions. Therefore, cleanly separating out institutional

share allocation sales from pure post-spin-off trading, and, consequently, analyzing the profitability of institutional

trading in the parent becomes problematic. On the other hand, given that th e equity of th e spun-off subsidiary is

listed independently only after th e spin-off, we are ab le to easily separate institutional share allocation sales from

pure post-spin-off trading in the subsidiary firms’ shares. We will, therefore, confine our empirical analysis of the

pattern and profitability of post-spin-off institutional trading to the subsidiary alone.

Page 8

period. Of the total allocation sales of subsidiary shares by institutional investors in the first y ear post-

spin-off, 70% occurs wit hin the first quarter after th e spin-off. Further, we find that allocation sales of

shares soon after the spin-off are significantly less profitable than sales of shar es held longer ter m. Our

allocation sales results suggest that institutional invest ors sell off subsidiary shares allocated to them in a

spin-off soon after the spin-off distribution when they do not have favorable private information about the

subsidiary’s shares, while holding s hares of fir ms regarding which they have favo rable private

information for a longer investment horizon.

What do our results tell us overall about the role of institutional investors in spin-offs? First, we

confirm that institutions indeed have an information advantage over ret ail investors regarding the future

prospects of the firm s involved in a spin-off. Further, this inform ation advantage i s greater for

subsidiaries compared to that for parent fir ms; smaller the subsidiary as a fraction of the pre-spin-off

(combined) firm, greater this information advantage. Second, our results indicate that spin-offs do indeed

relax a trading constraint existing prior to t he spin-off on institutional investors. Further, we show that

institutions take advantage of the a bove relaxation of their trading constr aint by trading differently in the

parent and subsidiary. these trading differences seem to be m otivated eit her by differences in the

information advantage institutions have with respect to the p arent versus that with respect to th e

subsidiary, or due to othe r differences between the parent and subsid iary such as risk or future growth

prospects. Finally, we show that institutions are able to realize short-term abnormal profits by trading in

the secondary market in the equit y of the subsidiary firm immediately after spin-off completion. Overall,

our results are consistent with institutions be nefiting signifi cantly from corporate spin-offs and

consequently motivating the management of undervalued firms to undertake such spin-offs.

Our paper is related to several strands in the literature. As discussed before, the theoretical papers

most closely related to this paper are those which develop a rationale for spin-offs based on how spin-offs

reduce the extent of asymmetric information between firm insiders and outsiders: see e.g. Chemmanur

Page 9

and Liu (200 5), Habib, Johnsen, and Naik (1997), and Nanda and Naray anan (1999).7 A number o f

empirical studies on corporate spin-offs have focused on value increases arising from spin-offs and have

documented positive announcement eff ects, positive a bnormal long-term stock returns, and increased

operating performance, respectively. following corporate spin-offs: see, e.g. Hite and Owers (1983),

Schipper and Smith (1983), and Miles and Rosenfeld (1983)) on announcement effects; Cusatis, Miles,

and Woolridge (1993) on long-term stock returns; and Desai and Jain (1999), and Daley. Mehrotra, and

Sivakumar (1997) on long-term operating performance. Chemmanur and Nandy (2003) document that the

efficiency of the plants constituting a firm i mproves on average following corporate spin-offs, and

identify the precise sourc es of these e fficiency improvements. Gilson, Healy, Noe, and Pa lepu (2001)

empirically document that there is an increas e in analyst coverage of firms following spin-offs and other

stock break-ups. A number of papers have tested alternative theories of corporate spin-offs: see, e.g. Ahn

and Denis (2 004), Dittmar and Shivdasani (2003), Burch and Nanda (2003), and Krishnaswami and

Subramaniam (1999). There is also a significant literatu re on the capital structure of post-spin-off firms:

see, e.g. Par rino (1997) and Ditt mar (2004). Fina lly, McConnell, Ozbilgin, and Wahal (2001) have

studied the long-term profitability of investing in the equity of spin-off firms.8, 9

The remainder of this paper is organized as fo llows: Section 2 summarizes the underlying theory

and develops testable hypotheses; Secti on 3 describes the data and m easures of institutional trading that

we use in our e mpirical analy sis; Section 4 presents the algorithm that we use for s eparating out

subsidiary share allocation sales from pure post-spin-off trading in the subsidiary ; Section 5 presents our

empirical tests and discusses results; and Section 6 concludes.

7 There are several other theoretical models of spin-offs based on considerations other than asymmetric information:

see, e.g. Aron (1991), and Chemmanur and Yan (2004).

8 Our paper is also related to the extensive literature on the role of institutional investors around various corporate

events: Chemmanur, He, and Hu (2005), and Gibson, Safieddine, and Sonti (2004) study the role of institutional

investors around SEOs; Ch emmanur and Hu (2005) study the role of institutional investors in IPOs; Gillan and

Starks ( 2003), C ornett et al (2 005) a nd a n umber o f other em pirical pape rs st udy t he rel ationship between

institutional ownership and firm performance.

9 Ab arbanell e t al (2 003) ex amine t he p ost-spin-off p rice pre ssure ca used by t he n oninformational t rades by

institutions driven by portfolio rebalancing needs. They, however, do not analyze the role of institutional investors in

corporate spin-offs.

Page 10

2. Theory and Hypothesis

In this sectio n, we will br iefly summarize the relevant theory and develop hypotheses for our

empirical tests.

Chemmanur and Liu (2005) m odel how spin-offs can potentially lead to an increase in

information production by institutional investors and their affiliated analysts about each of t he divisions

constituting a pre-spin-off co mbined firm. In their model, there are two types of institutional investors

who can produce information about a conglom erate firm with two divisions, A and B. Type 1 investors

have expertise (lower inform ation production cost) for producin g information about divis ion A of the

combined firm and a significantly higher cost of producing information about division B; conversely, type

2 investors have expertise only for producing information about division B and a significantly higher cost

of producing information about division A. Prior to the spin-off, type 1 institutional investors producing

information about division A and trading in the combin ed firm’s stock using this information are subject

to considerable “noise” arising from their lack of precise information about division B. This noise reduces

type 1 institutional investors’ expected profit fro m producing i nformation about division A of the pre-

spin-off firm. Similarly, type 2 i nvestors’ lack of precise information about division A reduces their

expected profit from producing information about division B of the combined firm. Spin-offs reduce the

above “noise” by allowing each institu tional investor to concentrate his investment only on the stock o f

the firm (division) about which he ha s private info rmation, thus increasing hi s expected profit and,

therefore, his incentive to produce information about that division. This means that spin-offs increase

information production about both divisions relative to the level of information production existing prior

to the spin-off. Fro m now onwards, we will refe r to the above hypothesis as th e information production

hypothesis.10

10 In developing hypotheses related to information production, we rely primarily on t he theoretical analysis by

Chemmanur and Liu (2005). This is because, while other models like Nanda and Narayanan (1999) and Habib,

Johnsen, and Naik (1997) have also argued that spin-offs improve firm value by reducing information asymmetry

between firm insiders and outsiders, the latter papers do not model information production by outsiders around

corporate spin-offs.

Page 11

The inform ation pr oduction h ypothesis generate s several testable predictions. The first

predication is that, while some institutional investors will have private information only about the parent,

others will have private information only about the subsidiary. Therefore, institutional investors trading in

the subsidiary will be different from those trading in the parent firm. In other words, a given institutional

investor will trade predominantly either in the parent or in the subsidiary, but not in both: i.e. there will

be an institutional “trading imbalance”. This is the first hypothesis we test in this paper:

H1 (Institutional Trading Imbalance): Upon the separation of the parent and subsidiary firm, there will be

a significant i mbalance in post-spin-off institutional trading between the eq uity of t he parent and the

subsidiary.11

The information production hypothesis suggests that institutional investors will choose to trade in

such a way as to maximize their expected profit from trading on their private information. This means that

they will choose to trade i n those spin-off stocks (either parent or subsidiar y) where their inform ation

advantage relative to ordinary (uninformed) investors is the greatest. Further, since, under the information

production hypothesis, institutional investors have greater expertise in producing information (i.e. greater

informational advantage with respect to ord inary investors) about one of the two div isions (firms)

resulting from a spin-off, the extent of the institutional trading imbalance will be greater as the difference

in information asymmetry between the parent and subs idiary involved in a sp ecific spin-off is greater.

This is the next hypothesis we test here:

H2 (Institutional Trading Imbalance and Information Asymmetry): The extent of the instituti onal trading

imbalance between the divisions in a spin-off will increase corresponding to the differences in the extent

of information asymmetry faced by (uninformed) investors in the equity of these divisions.

Institutional trading imbalance may also arise due to reasons other than private information on the

part of institutional investors. For example, as discussed in the previous section, the desire of institutional

11 If an institution continues to trade in the parent and subsidiary in the proportion of their shares outstanding after

the spin-off, we refer to this trading as “balanced.” Institutional trading imbalance measures the deviation from such

balanced trading. We will discuss in detail the construction of our measures of institutional trading imbalance in

section 3.3.

Page 12

investors such as mutual funds to better manage the risk of their own portfolios (“risk management”) may

also generate institutional trading imbalance, since institutions desiring to hold equity in high-risk firms

would buy additional equity in the high-risk division of the conglomerate firm immediately after the spin-

off, while selling off t he equity in the low-risk division (that they may have been allocated by virtue of

their share h oldings in th e pre-spin-off conglom erate firm); conversely, managers of low-risk mutual

funds may buy additional stock in the low-risk divisi on after the spin-off, while selling off equit y in the

high-risk division. This gives rise to the following testable hypothesis:

H3 (Institutional Trading Imbalance and Risk Management): The institutiona l trading im balance will

increase corresponding to the difference in risk between parent and subsidiary.

Finally, institutional trading imbalance may also arise due to the desire of inst itutional investors

such as mutual funds to make pure play investments in the equity of the individual firms resulting from a

spin-off. For example, growth funds can invest in the high-growth divisions and value funds can invest in

the lower growth but undervalued divisions (which may generate more r eliable cash flows) of a

conglomerate firm after a spin-off. Since many U.S. mutual funds are marketed to investors as “growth

funds” or “value funds”, splitting conglomerates into pure play companies can make the shares of the

resulting firms more attractive to these funds, increasing demand for the shares of both parent and

subsidiary. This gives rise to the following testable hypothesis:

H4 (Institutional Trading Imbalance and Pure Play Investment): The institutional trading imbalance will

increase corresponding to the difference in growth rates between parent and subsidiary.

The information prod uction hypothesis also has t estable implications regarding the information

content of institutional trading around corporate spin-offs. First, since the theory predicts that institutional

investors will have an informational advantage over ordinary (uninformed) investors about the parent and

subsidiary following a spi n-off, institutional trading around a spin-off will have predictive power for

future stock returns both in the short run (announcement effect of the combined firm) and in the long run

(the long-run post-spin-off returns of parent and subsidiary).

Page 13

H5 (Predictive Power for the Announcement Effect): Trading by institutional investors with privat e

information will have predictive power for the announcement effect of a spin-off.

H6 (Predictive Power for Long-run Stock Returns): Trading by institut ional investors with private

information will have predictive power for the long-ter m post-spin-off stock returns of the subsidiary and

of the parent.

Second, the information production hypothesis predicts that, the smaller the spun-off division as a

fraction of the combined firm, the greater the increase in information production by institutional investors

about that division due to the spin-off. This implies that institutional trading in a smaller subsidiar y (or

parent) will have greater predictive power for the fut ure stock returns of that subsidiary (or parent). This

gives rise to the following testable prediction:

H7 (Predictive Power and the Relative Size of a Spun-off Division): The s maller the subsidiary (or

parent) as a fraction of the combined firm, the greater the predictive power of institutional trading for the

future stock returns from that firm.

The information production theor y also genera tes two testable hypotheses regarding t he pattern

and profitability of institutional trading around corporate spin-offs. First, if institutional investors have an

informational advantage over retail investors about the subsidiary firm’s future performance, this will be

reflected in t he realized profitabilit y of their post- spin-off tradi ng, since one would expect them to

generate superior profits from such informed trading. This gives rise to the following testable hypothesis:

H8 (Profitability of Post-Spin-off Institutional Trading): Institutional investors will be able t o generate

superior profits by trading in the subsidiary around the spin-off.

Second, assuming that their private information is about the long ter m performance of the fir m,

institutional investors will sell the equity in spun-off firms about which they either do not have private

information (or have unfavorable information) soon after the spin-off distribution, while holding equity in

firms about which they have favorable private in formation longer (to be sold after their private

information is publicly realized, and incorporated in to stock prices). This gi ves rise to t he following

testable hypothesis:

Page 14

H9 (Profitability of Institutional Allocation Sales): Institutions will make superior profits on the sales of

shares in spun-off subsidi aries held for a longer inv estment horizon relative to those held f or a shorter

horizon.

3. Data and Measures of Institutional Trading

In this section, we describe the data and sa mple selection procedures, and construct measures of

institutional trading. Section 3.1 describes the spin-off sample and presents descriptive statistics. Section

3.2 describes the institutional trading sample and presents descriptive statistics. Section 3.3 describes the

construction of various institutional trading measures used in our empirical analysis.

3.1. Spin-off Sample

Our spin-off sam ple covers spin-offs which have a distributi on between January 1 999 and

December 2004. Our sample is obtained from three sources. We first obtain all the spin-offs listed in the

Securities Data Co mpany’s (SDC) mergers and a cquisitions database. S eparately, we us e the C RSP

database to identify all distribution events during the period with distribution codes starting with 37. The

two sources provide the initial sam ple of spin-offs. We then use FACTIVA news search to further verify

the character istics of these spin-offs, and to obtain additional inform ation such as the spin-off

announcement date. Following the spin-off literature, we focus our sample on tax-free spin-offs where the

parents control at lea st 80% of the share interests in the subsidiaries before t he distribution. We also

delete fro m our sam ple equit y carve-outs, two-stage spin-offs, merger motivated spin-of fs, spin-offs

where tracking stocks for the spun-o ff units already existed, spin-offs that are ADRs, sp in-offs with

concurrent security offerings, and spin-offs of close-end funds and REITs. The spin-off parents and

subsidiaries also need to be covered by the CRSP and COMPUSTAT database in order to be included in

our final sample. This procedure results in a total of 66 spin-off events.12

12 In four events, the parents had simultaneous distributions of two independent subsidiaries, instead of one. Two

parents had follow-on spin-offs which were part of the restructuring plan that were announced at the same time as

the first spin-off distributions. We exclude these follow-on distributions in our sample.

Page 15

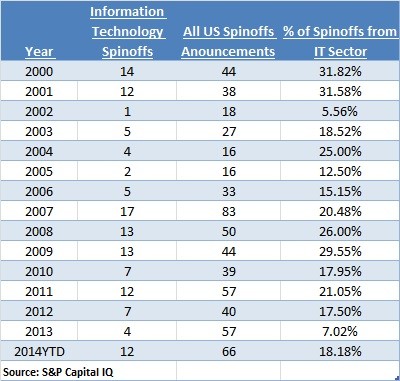

Table 1 provides the pattern of spin-off events over the six years covered by our sample, and the

descriptive s tatistics of the spin -off co mpanies b efore and af ter spin-off co mpletion. The y early

occurrence of spin-off events during this sample period is generally higher than that reported in previous

studies on spin-offs.13 Of the 66 spin-off parents prior to the distribution, sample institutions actively

engaged in t he trading of 56 firm s during the peri od starting fr om three months prior to the spin-off

announcement to the day before the spin-off distribution. Not reported in the table, the 10 firms not traded

by sample institutions are smaller, with lower market-to-book ratio and lower return-on-assets than the 56

traded firms. Similarly, the post-spin-off entities that retained such characteristics are also not traded by

sample institutions. The characteristics of these firms suggest that sample institutions may choose not to

actively trade the equities of these firms primarily out of regulatory and liquidity concerns.

For the firm characteristic descriptions provided in Table 1, other than the ma rket capitalization

that is measured on the day of the spin-off distributi on, all other pre-spin-off data are based on end-of-

fiscal-year information from COMPUSTAT and IBES prio r to the spin-off distribution, while the post-

spin-off data are based on the information available at the end of the first fisc al year following the spin-

off distribution. Market capitalization of the p ost-spin-off parent and subsidiary equals the closing price

of the firm’s shares times the total number of sh ares outstanding at the spin-off distribution date.

14 The

sum of the market capitalization of the parent and subsidiary is the market capitalization of the pre-spin-

off combined firm. Spun-off subsidiaries are in general smaller than their parents. On average, our sample

post-spin-off parents are about three times the size of their subsidiaries, based on book assets or on market

capitalization; this is si milar to that reported in previous studies on spin-offs. The market-to-book ratio

and return-on-assets ratio of parents are also generally higher than those of subsidiaries, both in terms of

13 For example, there are a total of 146 pure spin-offs during the 1965-1988 period reported in Cusatis, Miles, and

Woolridge (1993). Similarly, during the 1979-1996 period there are 106 spin-off events by 95 parents reported in

Burch and Nanda (2003). This comes out to about six spin-off events per year. The occurrence of spin-off events per

year almost doubled during our sample period compared with the early years, reflecting the increased level of spin-

off activity in recent years.

14 When the distribution is after market close, the next trading day is the first day that parent and subsidiary begin

their separate listings. In these cases, we treat the effective distribution date as the next trading day.