High court to weigh impact of fund fees CBS News

Post on: 17 Июль, 2015 No Comment

To the casual observer, the difference seems almost trivial. Imagine two mutual funds, identical in almost every way. They have the same management team, use identical investment strategies and even own the same securities in the same proportions. The only difference between them is that the retail fund charges a touch more — less than four-tenths of a percentage point more — in fees than the institutional fund.

That seemingly incidental difference recently caught the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court, and it could well mean hundreds of millions of dollars to American savers. The court recently agreed to review the case of Tibble vs. Edison International and will hear oral arguments in February.

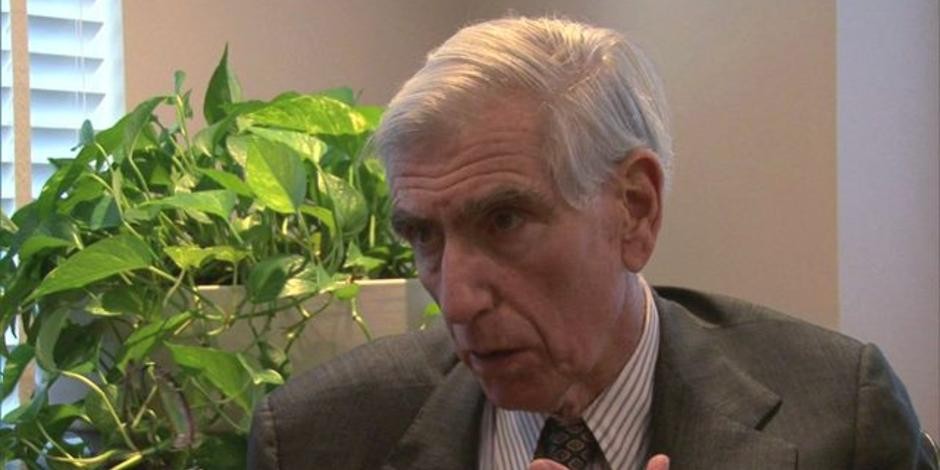

This will affect billions of dollars in retirement assets, says Jerome Schlichter, a St. Louis, Mo. attorney representing savers in the case against Edison International. This is a very important case for workers and retirees.

To understand what’s at stake requires a little background. Forty years ago, when companies still commonly promised long-time workers a set monthly pension at retirement, Congress passed a law called the Employee Retirement Security Act. Better known as ERISA, it ushered in a new type of tax-favored savings vehicle, the 401(k). And over the past four decades, companies have scuttled their traditional pension plans (known as defined benefit) in favor of this self-directed option (called defined contribution).

Companies sponsor their 401(k) plan by choosing a set menu of investment options and encouraging workers to save. Instead of getting a set monthly stipend at retirement, workers get the amount they saved (and any contributions their employers made to their accounts), plus investment returns. Today, more than 52 million workers have upwards of $4.3 trillion socked away in self-directed retirement plans.

However, when legislators wrote ERISA, they put in a provision designed to protect workers from self-dealing and careless management of their life savings. Figuring that each 401(k) would give workers just so many investment options, ERISA demands that plan sponsors exercise fiduciary duty to participants. That means the sponsors must put the interests of plan participants ahead of their own and ensure that workers are presented with attractive investment choices.

The problem? Because the costs baked into 401(k) plans aren’t easily seen, many plan sponsors packed their 401(k) programs with so-called retail funds — the same funds available to small individual investors — when they could have given their workers access to lower-cost institutional funds, says Schlichter. They did this, he contends, because it cut their costs of operating the plans while boosting the cost for participants.

That violates ERISA’s fiduciary responsibility provisions, he claims.

And yes, the difference in fees between the retail and institutional funds is small, with the retail funds charging between 0.2 and 0.4 percentage points more than the institutional funds. But the dollars involved are massive, both for individual plan participants and the companies involved. That’s simply because even small differences compound over time and can add to thousands of dollars for each of millions of savers.

Consider two employees, each investing $500 a month and earning the average stock market return of 10% over a 40-year time horizon. The only difference is Investor A puts his money in an institutional fund, which deducts just 0.2 percent in annual administrative costs. But Investor B’s contributions go into a retail fund that deducts 0.6 percent.

At retirement, Investor A has $2.9 million invested. Investor B has just $2.6 million. The $300,000 difference is the long-term cost of the 0.4 percentage point difference in fees.

Indeed, Schlichter has managed to win more than $150 million in settlements on behalf of 401(k) participants in other big plans, including those offered by Bechtel, Kraft (KRFT ), General Dynamics (GD ), Caterpillar (CAT ) and International Paper (IP ).

In this case, however, the court looked at the sticky issuer of whether recoveries could be limited when the offending investment had been in the plan for more than six years, the cut-off date for the statute of limitations. An appeals court said they could.

But Schlichter contends that such a limitation gives managers a free pass when their imprudent actions managed to go undetected for long stretches of time. He argues that each year a bad investment isn’t pulled out of the 401(k) plan, managers violate the law anew.

And he thinks workers should be reimbursed for the higher fees for the six years prior to when the suit was filed, no matter how long ago the offending fund had been added to the plan.

It’s worth noting that a lot has changed in the half-dozen years since Schlichter started suing big companies for failing to give their workers the lowest-cost investment options available. The government has demanded additional fee disclosures, and both companies and employees are paying more attention to the costs embedded in 401(k) plans, which has led to a systemic reduction in 401(k) plan costs.

This whole issue has been elevated to a position of importance as courts realize that what happens to worker assets in 401(k) plans has a big impact on their life after employment, Schlichter says.

Still, this case could affect several others, says Schlichter. If he wins, it will not only restore cash to the accounts of affected participants, it will put companies on notice that they’re expected to review their 401(k) plans every year and alter any past decisions that would not be considered prudent today.

Mr. and Mrs. Saver will get a long-term benefit, not just from fees coming down, but also from fiduciaries and sponsors understanding that they have an ongoing responsibility, he says. When you invest in a 401(k), you should get two things — the least costly investment choices available and an expert fiduciary on your side.

2014 CBS Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved.