Growth Versus Value Investing

Post on: 30 Май, 2015 No Comment

GROWTH Versus VALUE INVESTING

There has been an ongoing debate for many years as to whether higher stock market returns can be achieved by investing for growth or by investing for value. Investing for value means purchasing stocks at relatively low prices, as indicated by low price-to-earnings, price-to-book, and price-to-sales ratios, and high dividend yields. Investing for growth results in just the opposite — high price-to-earnings, price-to-book, and price-to-sales ratios, and low dividend yields.

Growth investors are more apt to subscribe to the efficient market hypothesis which maintains that the current market price of a stock reflects all the currently knowable information about a company and, so, is the most reasonable price for that stock at that given point in time. They seek to enjoy their rewards by participating in what the growth of the underlying company imparts to the growth of the price of its stock.

Value investors put more weight on their judgments about the extent to which they think a stock is mispriced in the marketplace. If a stock is underpriced. it is a good buy ; if it is overpriced. it is a good sell. They seek to enjoy their rewards by buying stocks that are depressed because their companies are going through periods of difficulty; riding their prices upward, if, when, and as such companies recover from those difficulties; and selling them when their price objectives are reached.

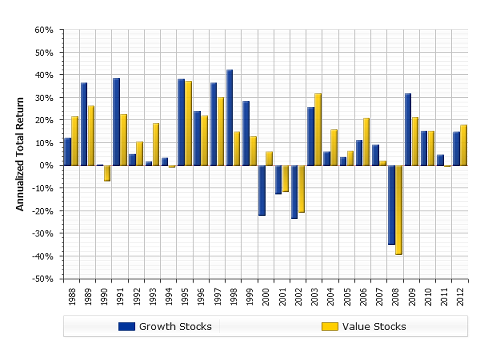

Which strategy shows the better returns depends, in part, upon the periods over which they are compared. It has, however, been my impression, over the past several decades, that value investing has received the more hype. It is the purpose of this paper to set the record straight.

Performance and Safety in Investments

One of the most fascinating aspects of the current mutual fund craze is the buying public’s utter disregard for the quality of the investments in the portfolios of the mutual funds it acquires. It is almost universally accepted that, if Fund A has gone up more than Fund B over some period of time, it is a better managed fund. How that performance was achieved tends to take a back seat to the performance numbers themselves.

How performance is achieved, however, can be of critical importance. The reason it can be important is that the stock market is fickle and, when it falls apart, it falls apart without warning. If a portfolio has achieved its performance by owning high-risk securities (e.g. small, less liquid companies with large amounts of debt, operating in highly cyclical, rapidly changing, or highly competitive industries) and/or using high-risk strategies (e.g. derivative securities such as options, futures, or warrants), it is not well-prepared for those difficult times which unexpectedly rock the securities markets about every quarter of a century or so.

Premiums for Safety

Let us recognize that we are naturally predisposed to pay a premium for safety. We stop and look both ways before we cross the street, in spite of the extra expenditure of time and energy it requires. We carry fire insurance on our houses, in spite of the improbability that our houses will burn down, and in spite of the many other things we might otherwise enjoy with all the money we pay for insurance premiums.

United States Treasury Securities are considered to be the world’s safest investments. But securities of agencies of the United States Government cannot be far behind. Federal Land Bank, Federal Farm Credit Bank, Federal Home Loan Bank, Federal Home Loan Mortgage, and Federal National Mortgage Association bonds all carry Moody’s ratings of Aaa. The former are considered safer because they are legal obligations of the United States Government, whereas the latter are only moral obligations of the United States Government. (The solvency of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation which insures our bank accounts, for example, is backed by a moral, as opposed to a legal, obligation of the U. S. Government.)

I ask my reader to contemplate a scenario in which the United States Government fulfills its obligations to pay interest and principal on its legal obligations but permits the obligations of its federal agencies (including FDIC insurance) to default. This, it would seem, would need to be an event more catastrophic than our republic has yet experienced, and certainly an event more serious even than the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Nevertheless, the marketplace pays a premium to own U. S. Treasuries, as opposed to Federal Agency bonds. A glance at the Wall Street Journal reveals that, for comparable maturities, bond buyers are willing to sacrifice between 1/2 of 1% and 1% in yield to own the former, rather than the latter. As improbable as it is that the incremental safety afforded by Treasuries over Federal Agencies will ever be needed, investors are willing to pay a substantial premium (sacrifice in yield) to own them.

The same situation exists with municipal bonds. In spite of the fact that the general obligations (GOs) of a state are backed by the taxing power of all of the assets within that state, Aaa state GOs yield less than Aa state GOs.

The differential between Aaa corporate bonds and Aa corporates provides still another example. The sacrifice in yield required to own a Aaa corporate versus a Aa corporate is of the order of 1/2 of 1%. Again, imagine the economic or monetary scenario in which Aaa corporate America meets its obligations, but Aa corporate America defaults.

Given that municipal bonds are considered less safe than U. S. Government bonds, that corporate bonds are considered less safe than municipal bonds, and that a company’s common stock is always less safe than its weakest bond, should we not expect that the marketplace might be willing to pay a premium for safety (as well as for appreciation potential) in a common stock?

The important principle to understand is that, given two common stock portfolios, A and B, if Portfolio A is made up of higher quality issues — companies less apt than those in Portfolio B to go bankrupt in a period such as the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Great Credit Crunch of the 1970s, or an economic/monetary scenario more catastrophic than has yet been experienced — then, barring the occurrence of such a catastrophic event, and all other things being equal, Portfolio A should show a lesser return than Portfolio B. Portfolio A must pay an insurance premium for its added protection against catastrophic events, as improbable as their realization may seem. It should expect to pay this premium by accepting lesser total returns, in the absence of a catastrophic event.

New Morningstar Data

The Morningstar mutual fund service is the most popular and most comprehensive of all the mutual fund rating services. Beginning in late 1996 and early 1997, the service modified the way it categorized mutual funds. Common stock funds are now divided into nine groups, according to whether they invest in large capitalization, medium capitalization, or small capitalization companies, and whether their investment styles are predominantly growth oriented, value oriented, or a blend of the two. For the first time, this data gives us an opportunity more easily to study, compare, and contrast the collective character of the portfolios, and the performance records, of large numbers of mutual funds using growth and value stock approaches as their investment strategies.

The data used for this analysis covers over twelve-hundred mutual funds with over $1/2 trillion in assets. Morningstar makes such an analysis relatively easy because it publishes a page for each investment style which it calls an Overview. On this page is a listing of the twenty-five largest holdings of all the mutual funds in each sector, the relative size of each position, and the collective performance data for the funds in that sector. By examining the quality of the twenty-five largest holdings of the mutual funds in a sector, we can get a pretty good picture of the character of the portfolios in that sector.

Measuring the Quality and Safety of Large-Cap Portfolios

The most popular, and probably the best, way to measure the safety of a common stock is to look at its Standard & Poor’s rating. Standard & Poor’s rates most large capitalization stocks, and a portion of the universe of mid-cap and small-cap stocks, on a scale of A+, A, A-, B+, B, B-, C, and D. These ratings are in no way meant by Standard & Poor’s to be prognostications of performance in normal markets. They are meant more to serve as measures of the degrees of protection available in each security in a catastrophic market.

Based upon the twenty-five largest holdings in the collective portfolios of the large capitalization growth and large capitalization value sectors, a profile of each sector appears in the following table: