Does Redistributing Income from Rich to Poor Increase or Reduce Economic Growth or Welfare Posner

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Welcome to the new Becker-Posner Blog, maintained by the University of Chicago Law School.

12/29/2013

Does Redistributing Income from Rich to Poor Increase or Reduce Economic Growth or Welfare? Posner

The United States spends heavily on redistributing income by taxing the affluent and using the revenues from taxation to support a variety of federal and state means-tested welfare programs, such as food stamps, Medicaid, social security disability benefits, and the Earned Income Tax Credit. And a number of other programs, such as social security retirement benefits, unemployment benefits, the minimum wage, Medicare, and subsidies for education, have a large redistributive component, though they are not means-tested. The aggregate annual amount of redistributive transfers is in the trillions of dollars.

Conservatives want to cut expenditures on such programs in order to limit taxation and the national debt and also to encourage work. Some of them agree with Mitt Romney, who famously in his unsuccessful 2012 presidential campaign described the lower half of the income distribution in the United States as composed of persons unwilling to take responsibility for their lives. (He issued a retraction.)

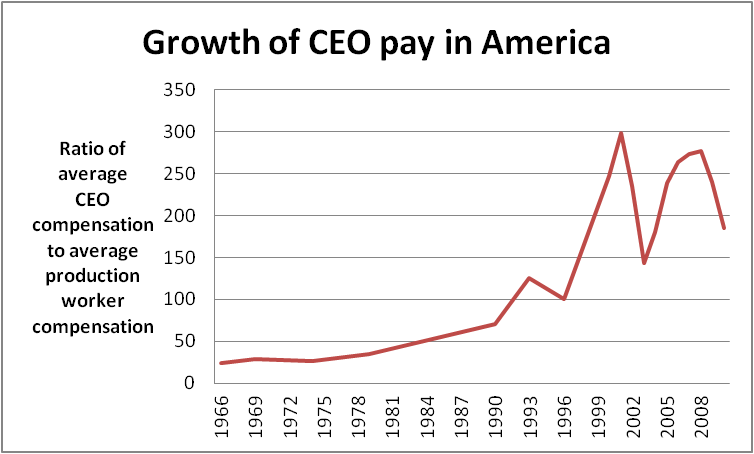

Despite redistribution, economic inequality in the United  States has risen in recent decades. In 1982, the top 1 percent of American earners received 13 percent of total income; by 1997, this had increased to 17 percent; today the figure is 22 percent. The poorest 20 percent of U.S. households have only 5 percent of the nation’s total personal income and the richest 20 percent have 50 percent. Between 1997 and 2008, median U.S. household income fell by 4 percent after adjustment for inflation, and between 2007 and 2011 it fell by 8.9 percent. A median is not an average; average income rose because the incomes of high earners rose—and so the effect was actually to increase inequality of income.

The trend of rising inequality appears to be attributable mainly to increasing returns to well-educated people as a consequence of a shift in the economy to methods of production and distribution that require application of knowledge and intelligence—in other words, the dramatic increase in automation as a result of the computer revolution—rather than strength or stamina, but to other factors as well, such as falling marginal income tax rates. The growth in automation is unlikely to stop or slow—in fact it seems likely to speed up—and so without substantial social intervention the trend of rising inequality is likely to continue. (The Affordable Care Act will have some redistributive effect, but how great a one cannot as yet be predicted.)

Rising inequality of income and wealth creates anxieties that can have dire economic consequences by increasing the demand for trade protection, restrictions on immigration, union protections, other anticompetitive measures, and government subsidies; it can also create class resentment, and thus lead to inefficient regulatory measures. The economist Raghuram Rajan speculates that increased inequality was an indirect cause of the financial meltdown of 2008 and the ensuing economic crisis.

Measures to reduce income inequality, especially measures that raise the median household income (as distinct from reducing inequality by leveling down the incomes of the well off, which could have serious disincentive effects), could increase economic efficiency by reducing political pressures for inefficient policies. That was the rationale for the adoption by capitalist nations of “socialist measures,” beginning with Bismarck’s programs of government health, accident and disability insurance, and old-age pensions—all designed to secure capitalism against communism and other radical political ideologies.

So let me consider the costs of increased redistribution from the top of the income distribution ladder to the bottom. I’ll assume that the redistribution is financed by taxation, with higher tax revenues generated either by higher marginal rates or by reducing deductions and exemptions. So the national debt would not be increased. The social cost of the redistribution would be limited to reduced work effort.

But this involves a paradox: redistribution is challenged on the ground that it undermines the work ethic of both the rich and the poor—the reduction in the (after-tax) income of the rich, brought about by redistribution, causes them to work less but so, it is argued, does the increase in the income of the poor. Both groups, the argument goes, are incentivized to substitute leisure for work. Besides being contradictory, neither point seems powerful. It is not surprising that there is very little evidence that increasing marginal income tax rates reduces work effort. A person who responds to a fall in his (after-tax) income by working less compounds his loss of income. Leisure is unlikely to be a good substitute. High-income people who work hard tend to like both working hard and making money, and they are likely to be highly competitive, and want to keep abreast or ahead of their peers in money making. Furthermore, most high earners are employees rather than being self-employed, and few employees, even among the highly paid, have any job security. If they respond to a higher marginal tax rate by working less hard, they not only further reduce their net income and jeopardize their chances for generous bonuses and rapid advancement; they may well jeopardize their employment. Suppose a person who earns $250,000 before federal income tax pays $50,000 in tax, and now his tax bill is increased by 20 percent, to $60,000. Will he work less hard? That seems unlikely to me. I think if anything he’s likely to work harder.

The more serious effect of higher marginal tax rates than the effect on the work ethic is the effect in inciting a search for loopholes, creating pressure for new loopholes as well and also shifting effort to activities that involve big tax breaks, including foreign investment. A better way to increase tax revenues than raising tax rates is tax reform that broadens the tax base by eliminating deductions and exemptions that serve no economic or other social purpose. The important thing from the standpoint of income redistribution is to increase tax revenues by one means or another.

At the bottom of the income distribution, there is a real reason for concern about the effects of redistribution on the work ethic: the incremental income from working may be negligible if the increment carries the recipient of benefits over the benefits threshold: he may lose in benefits all of or even more than his income increment from working. This effect is recognized, however, and can be eliminated or at least reduced by a graduated reduction in benefits, to assure that benefits fall by significantly less than the recipient’s increased working income.

There is evidence that increasing the length of entitlement to unemployment benefits elongates job search by the unemployed. This is not necessarily a bad thing, because a longer search may result in a better job. Offsetting this is the risk that employers will worry that a job applicant who has not worked for many months will have lost skill and motivation—but knowing this, the unemployed will be reluctant to protract their period of unemployment by not looking for work vigorously. Notice too that curtailing unemployment benefits will push more unemployed workers to seek social security disability benefits, upping the cost to the taxpayer.

If, as I suspect, a modest increase in marginal tax rates (or diminished deductions or exemptions), with the revenues generated by the increase used to increase welfare benefits, would have few adverse effects on economic output, the reduction in economic inequality that would result would be cost-justified by the effect on the adverse socio-economic costs, listed earlier, of the current high level of income inequality in the United States.

Posted at 10:02 PM | Permalink