China and India s Battle for Influence in Asia

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Japan as an Economic Counter-Weight to China

The recent signing of a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement between India and Japan will soon make each country the other’s largest trading partner. Both remain concerned about the rising power and influence of China, now the world’s second largest economy, projected to surpass the U.S. in size as soon as 2020. India has for some time been alarmed by China’s military links with Pakistan and its growing presence in the Indian Ocean. Japan is still coming to terms by being supplanting as the world’s second biggest economy, and by China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea.

There are clear economic benefits to be gained by India and Japan by forging closer ties. Japan is keen to enhance its accessibility to rare earth metals, which are vital to the high tech Japanese economy. A recent maritime conflict with China and the subsequent disruption in the supply of the rare earth metals has placed diversification of supply firmly on the Japanese agenda. For India, the removal of Japanese tariffs on tea and other agricultural products is expected to be of enormous benefit, while India eyes Japanese contractors to invest in and upgrade its poor infrastructure network.

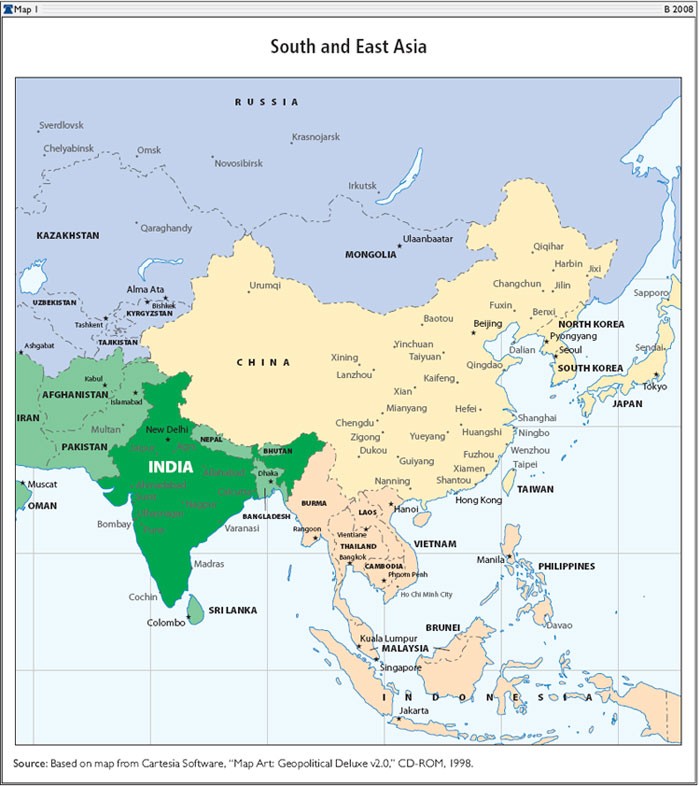

The deal is the latest in an emerging pattern of greater economic cooperation between India and a region looking over its shoulder at China. In addition to Japan, India has over the past six years signed bilateral trade agreements or more comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with Nepal, South Korea and the ten-member Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) (ASEAN includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam). Given an existing agreement with Sri Lanka and ongoing negotiations with Bangladesh, the agreements cover the majority of Asian economies.

China has been equally busy signing agreements with ASEAN, New Zealand and Pakistan, while negotiations are ongoing with Australia and South Korea. China’s economic and political presence Asia, Africa and Latin America has been growing rapidly. Its penetration in the region — from financing large construction and infrastructure projects, to its voracious appetite for natural resources — has worried India, which fears being marginalized in its own backyard. Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has made enhanced economic and political relations in Asia his foreign policy priority — with intent to counter China’s growing assertiveness.

The burgeoning Indian-Japanese relationship may ultimately impact China’s ability to achieve its own objective of strengthening bilateral ties with a number of countries in the Asia region. India is effectively reinforcing the concept of Japanese centrality in Asian affairs, something that had been waning in recent years. India has also recently engaged in security talks with Malaysia and South Korea, and has been courting the region’s foremost naval power, Indonesia.

President Yudhoyono is keen to forge partnerships with India’s defense sector, while India sees Indonesia as an important strategic partner in constraining the growing Chinese presence from the Bay of Bengal to the Malacca Straits. Every year since independence India has invited a special guest who embodies India’s strategic, economic and political interests at the time; 61 years after Indonesia’s first president — President Sukarno — was guest of honour, the 2010 signalled a realignment of the two countries’ strategic interests, with President Yudhoyono attending the event.

India’s Look East

While being historically suspicious of Indian intentions, Southeast Asia holds a much stronger dislike of China than of India. Chinese machinations in the region are still prominent in popular memory, given China’s 1979 invasion of Vietnam, its support of the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia (1976-1979), and accusations of involvement in Indonesia’s 1965 coup.

Furthermore, China still has unresolved border disputes with several nations in the region, including Bhutan, Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia, as well as claiming a sizeable chunk of the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. Tibet of course remains a sore bone of contention in Sino-Indian relations, and China’s belligerence in relation to a sea collision between a Chinese fishing boat and Japanese patroller last September caused considerable consternation in the region and has prompted many countries to forge or strengthen regional alliances with respect to security.

India’s diplomacy has been heavily focused on East and South East Asia for 20 years now. Having already signaled the renewed prominence of India Look East policy, Prime Minister Singh has visited Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam over the past 12 months. A multi-faceted policy, Look East aims to improve economic and political ties with the region and attempts to carve out a place for India in the larger Asia-Pacific dynamic. One factor helping India in this regard is its own democratic political system, prompting many countries in the region to view India’s own economic rise to be relatively benign and something to be welcomed. Being the world’s largest democracy lends a certain degree of transparency to India’s foreign policy motives, something that is worryingly absent from relations with China. A regional order dominated over the past two decades by open markets, international cooperation and an evolving democratic community backed by Washington’s diplomatic and security ties, has also facilitated India’s growing stature among its regional neighbors.

The stark difference in political systems has at times appeared to be both sides’ Achilles heel, however. For India, adherence to democratic norms, checks and balances has hindered its ability to achieve its larger regional goals. For example, for decades India refused to have any relationship with Myanmar, leaving an opening for China, and long-held political tension with Sri Lanka hindered closer ties between the two countries — a gap that China since has fully exploited. For China, whose leaders have no qualms with benefiting from economic opportunities in countries with distasteful human rights records, opaque decision-making has bred mistrust amongst its regional neighbors, who fear China’s intolerance of political pluralism may spill over into its international relations. Almost every country in the region has a sizable Chinese minority population — another factor that has encouraged governments to befriend India as a counterbalance to Chinese influence.

Sri Lanka’s Role

Long viewed by India as firmly within its sphere of influence, India has been concerned by Colombo’s active solicitation of Chinese aid and investment, with China now Sri Lanka’s number one aid donor (more than US$1bn per year), main trading partner, and majority supplier of more than half the country’s construction and development loans. The construction of the Hambantota Development Zone has been a particular source of concern. China is financing 85% of the zone, which will house an international container port, oil refinery and international airport, as well being used as a refueling center for both countries’ navies. India claims the zone will increase China’s intelligence-gathering capabilities vis-a-vis India, but both Sri Lanka and China have dismissed such concerns, claiming the site is a purely commercial venture. Where India is preoccupied by domestic sensitivities — particularly from its Tamil population, angry at the way Tamils have been treated in Sri Lanka since the 2009 defeat of the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam — China faces no similar issues. The Rajapaksa regime has welcomed Chinese overtures with open arms; India has been scrambling to catch up.

Sri Lanka is merely one front in a broader battle for control of the Indian Ocean. China has steadily built Indian Ocean ports in Bangladesh (Chittagong), Burma (Kyaukphyu) and Pakistan (Gwadar), while also steadily assisting Pakistan’s naval expansion, much to the chagrin of India. India has referred to Sino-Pakistani cooperation as detrimental to regional peace. But in the Indian Ocean, at least for the moment, India has the upper hand, having boosted its naval spending to 15% of its total defence budget over the past five years in an effort to protect what it views as ‘India’s Lake’. With two aircraft carriers under construction as well modernizing its radar and surveillance hardware, India is keeping pace with China’s naval modernization program, though with fewer fiscal resources. India’s total defense budget for 2011 is approximately $34 billion, while China’s is estimated to be approximately $92 billion. Where India has the benefit of having to focus on only one ocean, China has been preoccupied with securing the island chains stretching from Japan to Malaysia. For the time being at least, there is space for both countries to maintain military supremacy in their own distinct backyard.

The Battle Will Last

For the moment, India and China will continue their respective economic and political ascent relatively harmoniously, as there is plenty of scope for both countries to flex their muscles in their own neighborhood. China’s main allies in the region have been ill-chosen, with North Korea, Myanmar, and Pakistan all being perceived as bad boys for one reason or another. India on the other hand, has aligned itself with countries where it appears to have more to gain than lose (Japan, Indonesia and Vietnam, amongst others). India also appears to be making more headway than China in the battle for hearts and minds, which bodes well for the long-term future of Indian relations throughout the region. This suggests that India has the upper hand in the medium-term. However, while China’s rise has been met with suspicion and in some cases alarm, it remains many Asian countries’ largest trade partner, donor, and source of investment.

Anyone who underestimates China’s ability to learn quick lessons and adapt to dynamic investment climates will be disappointed. China has proven itself to be a shrewd and cunning competitor in the global economic and political landscape, and its ability and willingness to hurl money at countries yearning for assistance will continue to enhance its influence throughout the region for many years to come.

Daniel Wagner is Managing Director of Country Risk Solutions, a political risk consulting firm based in Connecticut, and also Senior Advisor to the PRS Group. Daniel Jackman is a Research Analyst with CRS.