Changes in NAV Responding to changes in mutual fund prices

Post on: 29 Май, 2015 No Comment

Interpreting and Responding to

Mutual Fund Price Fluctuations

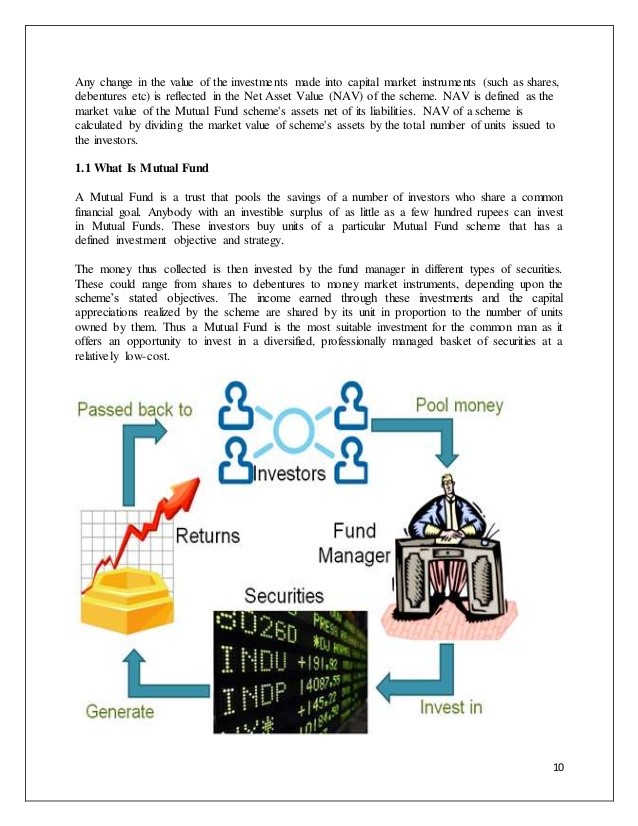

Changes in net asset value (NAV) should not elicit the same response as changes in the per-share prices of individual securities. Mutual fund prices are always determined by dividing the funds’ net assets by the number of shares outstanding to arrive at their net asset value. When first exposed to mutual funds, some people have the mistaken perception that mutual fund shares are subject to the same market forces as shares of stock. However, this is not correct, as the number of shares outstanding always varies in direct proportion to net sales and purchases, thus supply and demand are not an issue, as they are with individual securities in the short term.

As noted in a prior subsection, the initial price per share selected by a fund’s managers can have a psychological effect on the initial demand for a fund’s shares. As mutual fund shares are purchased in dollar amounts, rather than in round lots of 100 shares as are stocks, the price per share is irrelevant and thus the psychological effect is irrational, but that’s human nature for you. This assumes, of course, that the price per share is within the normal bounds for mutual funds, which is usually less than $100 per share.

Market forces do not directly cause changes in NAVs, i.e. mutual fund prices. Rather, the value of a fund’s shares is determined by the effects of market forces on the securities held in the fund and from which the fund’s shares derive their value (NAV). This is explained by the fact that mutual fund shares are not subject to the effects of supply and demand because the number of shares outstanding always varies with demand. You may think that I’m splitting hairs and that the difference is just a matter of semantics, but I’m not splitting hairs and it’s not a matter of semantics. The difference is significant, although it may sound subtle. It’s very important that you understand this, as not understanding it could result in some very dysfunctional behavior on your part.

What kind of dysfunctional behavior? Well, I’ve witnessed many people reacting to changes in NAV as if the mutual fund’s shares were shares of stock of an individual company, of which there is a fixed supply in the short term. In the short term, buying and selling frenzies can cause a stock’s price to move well above or below its intrinsic value. Market psychology powers momentum, and supply and demand also play a significant role here. In such cases it makes sense to do the opposite of everyone else, which would result in selling high and buying low, respectively.

Thanks to the diversification provided within mutual funds, significant short term disparities between market price and intrinsic value are much less likely, and supply and demand will never be a factor. Mutual fund prices should never spike, up or down, as far or as quickly as individual securities. The rational response by mutual fund investors to large changes in NAV is to rebalance their portfolios when the predetermined weightings of their holdings reach their trigger points. In the long run this will result in buying low, selling high and maintaining the appropriate asset allocation.

Some mutual funds will move faster and farther than others. This is especially true with sector funds, as their diversification has depth but not much breadth, so they can be subject to frenzies within a sector, such as technology funds during their rise and fall in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In this case nearly all technology stocks were selling well above their intrinsic value. Then, after the fall, a lot of solid companies were selling well below their intrinsic value. Although this unusual situation is somewhat contrary to some of what I stated above, it supports my conclusion. This can best be explained by an example.

If you had decided that you wanted a technology fund to make up 10% of your portfolio and you would rebalance whenever your technology holdings grew to 15% or shrank to 5%, then you would have repeatedly been selling off some of your technology fund’s shares every time their value reached 15% of your portfolio’s value. Each time they reached 15%, you should have sold 1/3 of your position to bring your technology holdings down to 10%. Then, when the bubble burst, each time your remaining technology holdings dropped to 5%, you would have bought enough to bring your holdings back up to 10%, although it would probably have been best not to do this while they we obviously in free-fall.

By following this strategy, which is, in essence, dollar cost averaging, on the way up you would have constantly been taking your returns from technology (selling high), and thus locking in those returns and limiting your exposure to that sector, and investing it in under-performing asset classes (buying low). On the way down you would have rebalanced by selling shares of funds in asset classes that were doing well (selling high) to fund the purchase of technology funds (buying low).

I’m sure you see the pattern: buy low/sell high. It sounds easy but it takes discipline, which really just requires a mindset. Asset allocation is what it’s all about; that’s what accounts for at least 90% of your success as an investor. Once you’ve determined the appropriate asset allocation for you, rebalancing is how you maintain that allocation. Don’t let temptation lead you off track, and don’t misinterpret changes in NAV.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Section Intro Next Section