Bond Run Is Wall Street s WorstCase Scenario

Post on: 19 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Illustration by 731

(Scout Unconstrained Bond Fund was incorrectly described as an exchange-traded fund. It is an open end mutual fund.)

All it takes is a few mouse clicks to buy shares in the Scout Unconstrained Bond Fund (SUBFX ). an open-end fund that tracks a concoction of debt tied to the government, financial firms, mortgage pools, and other entities.

And all it takes is a few mouse clicks to sell—something that has begun to worry Wall Street. Since the financial crisis, $900 billion has flowed into ETFs and bond mutual funds, bringing the industry’s total holdings to $3 trillion. Fund investors who sell shares get their money back almost immediately, as if they were making a withdrawal from a money-market fund. The bonds that the funds own are far less liquid, often trading in telephone conversations or e-mails between brokers, away from exchanges. If too many people decide to get out of bond funds at the same time, the wave of selling could lead buyers to sit on their hands, bringing the system to a halt.

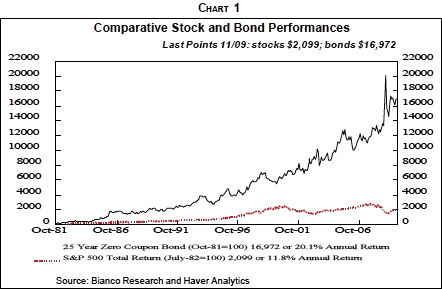

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve has kept short-term interest rates near zero to spur borrowing and boost economic activity. The unemployment rate has fallen to 6.3 percent, below the Fed’s target of 6.5 percent, and the central bank is curtailing its easy-money policies, reducing the amount of bonds it buys each month and getting closer to raising its benchmark interest rate. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg say rates could rise as soon as the end of this year.

$900b

Money flowing into bond mutual funds and ETFs since the financial crisis

The Fed’s low-interest-rate policy reduced the yields on safe, short-term vehicles such as money-market funds, savings accounts, and CDs, and led investors to seek higher returns from bond funds, including ones that invest in risky high-yield debt and other speculative issues. Unlike money-market funds and CDs, though, bonds lose value when rates rise, depressing the prices of bond mutual funds and ETFs. And the riskier the bond, the more vulnerable it is to rising rates. Wall Street firms are warning clients that if fund investors who view bonds as safe are hit with sudden losses, there could be something akin to a run on the bond market.

The worry isn’t only that investors’ bottom lines would take a hit. It’s that a mass selloff could swamp the market, with demands for redemptions forcing fund managers to unload their bonds at rock-bottom prices. The ensuing losses would encourage even more investors to redeem, perpetuating the downward spiral.

There’s a risk “that when the Fed starts hiking in earnest, outflows from high-yielding and less liquid debt will lead to a free fall in prices,” wrote Jan Loeys, chief market strategist at JPMorgan Chase (JPM ). in a June 20 report. “In extremis. this could force a closing of the primary market and have serious economic impact.” Companies might have trouble raising the money they need to function, in what would be an echo of the credit freeze of 2008.

BlackRock (BLK ). the world’s largest asset manager, with $4.4 trillion under management, suggested in a May paper that regulators consider redemption restrictions for some bond mutual funds, including fees for large redeemers. The Financial Times stoked Wall Street chatter with a June 16 report that the Fed was studying exit fees to reduce the chances of a run on the corporate bond market; Fed Chair Janet Yellen said at a press conference on June 18 that she was “not aware” of any such discussion.

“I would posit that whatever the next crisis is, is likely not to be the one that everyone’s worried about today.”—Eric Jacobson, Morningstar

Some market analysts say the fears are overblown. “Many funds already carry a fair amount of cash” to meet redemptions, Ira Jersey, director of U.S. rates strategy at Credit Suisse, wrote to clients on June 24. Taxable bond funds have 9.5 percent of their portfolios in liquid assets such as cash and U.S. Treasuries, according to Credit Suisse, more “than most would assume.”

Brian Reid, chief economist at the Investment Company Institute, says interest rate shocks are nothing new, and the system has held before—as in 1994, when the Fed doubled its benchmark rate to 6 percent over 12 months, catching many investors unprepared. “Markets aren’t nearly as fragile as people worry about,” Reid says. “I would put ‘massive outflows from bond funds’ at such a low level of probability—even during the financial crisis we didn’t have that—it doesn’t rise to the level of systemic risk that has been portrayed.” Regulators and market commentators who warn about systemic risk too often could numb investors to actual problems, he says—the Chicken Little syndrome.

Eric Jacobson, co-head of fixed income at Morningstar, also contends that the peril has been overstated. “It would be an act of hubris to say there’s no risk,” he says. “But I would posit that whatever the next crisis is, is likely not to be the one that everyone’s worried about today.” A surprising 1.4 percentage point surge in the 10-year Treasury yield over the last eight months of 2013 led to outflows of $77 billion, or 2.7 percent of industry assets, according to ICI. Inflows resumed in 2014. “To the extent that people might act on it, it’s already begun,” Jacobson says. “By the time we may get to anything that resembles a scary outcome, a lot of the fearful money will have already moved.” The mid-2013 selloff caused at least two financial companies, Citigroup (C ) and State Street (STT ). to temporarily stop some cash redemptions for ETFs. And selling pressure led several ETFs to trade for less than the value of their holdings.

One new source of uncertainty since 2008 is the role banks will play when the Fed eventually raises its target rate. The biggest banks, faced with new rules meant to curb risk, have reduced their trading operations—making it harder for them to opportunistically buy large chunks of bonds they could hold and then sell at a profit over time. That means they no longer have the same power to act as stabilizers in a tumultuous market. “Wall Street dealers are not fulfilling the same sort of function that they were 10 years ago,” Jacobson says. “So much of the market capacity that the banks used to handle has essentially shifted to mutual fund owners.” And in an exodus, bond fund investors may be more likely to join the crowd than go against it.