Boards and Corporate Governance A Balanced Scorecard Approach HBS Working Knowledge

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

HBS professors Robert S. Kaplan and Krishna G. Palepu discuss a Balanced Scorecard approach to how companies can create shareholder value through more effective governance.

Companies can create shareholder value through more effective governance, and through boards that do not simply ensure compliance, but focus their time and efforts on the most critical strategic areas.

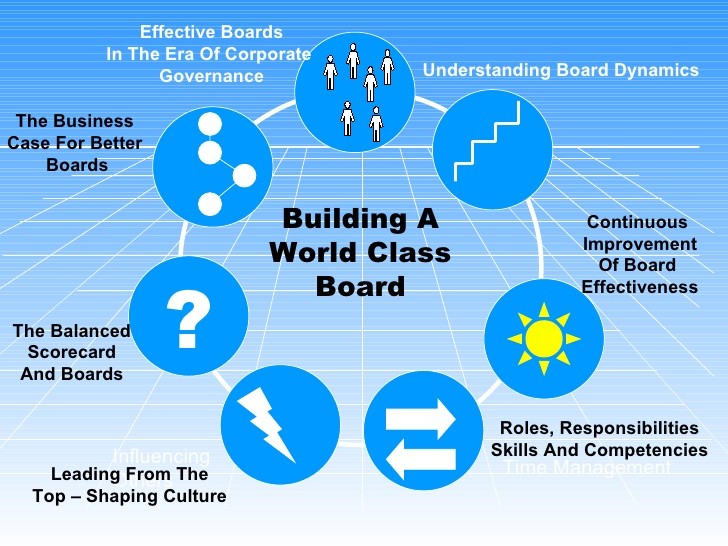

Past board results have often not been outstanding, and the challenging current climate makes board performance even more difficult. Effective boards are those that take the initiative to design clear and focused forward-looking agendas, concentrating board energy on a company’s specific value drivers, and then employing tools and information systems to help them monitor the company’s performance. The Balanced Scorecard approach has evolved into a tool that can be used to help companies create greater value at the business unit level, the corporate level, and the board level. This is done through three Balanced Scorecards that are linked and work together: the Enterprise Scorecard, the Board Scorecard, and the Executive Scorecard. These Scorecards clarify goals, priorities, processes, and ownership, and define the linkages between desired financial results and the actions needed to achieve them.

Context

Professor Palepu examined why a governance system is essential in a complex modern economy, and how governance systems differ internationally. He discussed the key functions of boards and reviewed the challenges boards currently face. Professor Kaplan addressed techniques and tools boards can use to improve effectiveness, and shared how use of the three-part Balanced Scorecard framework can serve as the cornerstone of both effective management and sound governance.

Key Learnings

A sophisticated governance system is necessary in a complex capitalistic economy to ensure that capital funds the best ideas. The financial system in a capitalistic economy ideally channels capital to the best ideas, weeding out the bad ones. Investors have the challenge of sorting through the overwhelming number of ideas to discern the good ones, a process compared to finding a needle in a haystack. They often lack the information necessary to make good investment decisions. At the same time, managers and corporations seek capital for their ideas, but in doing so they have an inherent conflict of interest about what information to disclose.

Therefore, for this complex system to work smoothly requires a governance system where standards setters and regulators define disclosure requirements and other rules, and boards and managers comply. Economies with good governance structures perform better than those lacking such systems.

A board’s key functions are overseeing a company’s strategy and leadership, monitoring its financial results, and ensuring compliance with regulations. A board’s most important function is approval and oversight of strategy and of major strategic decisions, such as acquisitions and large capital expenditures. Boards are responsible for selecting (or replacing) the CEO, counseling and supporting the CEO, compensating management, and planning for succession. A board is responsible for overseeing and monitoring the firm’s financial performance, for oversight of shareholder and stakeholder communications, and for ensuring compliance with regulations. While the emphasis and time devoted to compliance has increased, compliance is not a value-creating activity.

It would be unfortunate if boards focused only on compliance and didn’t engage in functions that create value.

Robert S. Kaplan

The board role is significantly different than that of the CEO, who is charged with running the business. The CEO is responsible for defining and communicating the strategy, aligning the resources (financial and human) to achieve the strategy, and managing the execution of the strategy.

Board performance of core functions has not been stellar. The performance of many boards has been problematic, leaving much room for improvement. In addition to the accounting scandals, companies have engaged in earnings games, evidenced by widespread earnings restatements: Over the past five years there have been more than 1,000 restatements, reflecting a lack of board oversight.

Many companies have experienced strategy failures, which reflect poorly on the boards that approved these strategies. For example, about two-thirds of acquisitions fail to break even. Because acquisitions require board approval, they are a clear measure of board decision-making. The fact that so many acquisitions fail to break even calls into question the strategy and decision making process employed by many boards.

In addition, shorter CEO tenures indicate that boards often fail to hire the right person. Boards also often choose the course of dismissing a CEO versus taking corrective action. Also, in many instances, boards have not truly linked executive compensation to performance, as they often fail to rein in pay when performance suffers.

Expectations placed on board members have increased. Most notably, Sarbanes-Oxley and the new listing requirements of the public exchanges have significantly increased the responsibilities on, and the scrutiny of, directors. Independent directors are now expected to play a greater role, audit committees are required to take on greater responsibilities, and senior managers and boards are being held more accountable for the veracity of company results.

These greater responsibilities take a considerable amount of director time and detract from other, more strategic, director roles. Also, as regulations mandate more outside directors, many of these directors lack the necessary knowledge about the industry and business, requiring education about and acclimation to a company’s business to serve effectively.

To improve effectiveness, boards must use their limited time for more strategic, value-adding purposes. Due to the greater demands on board members, it is essential that boards focus their limited time on what is strategically critical. This entails defining a company’s key drivers of value, key capabilities, and critical processes, and designing a board agenda and information system focused on tackling and monitoring these value-drivers, capabilities, and processes.

Boards require the increased visibility that effective information systems can provide. Well designed information systems enable early identification of problems so they can be addressed and corrected. Boards also require information that is more forward looking, and not just a summary of the past, so that board discussions can be more strategic.

In the boardroom, performance can be enhanced by using time more effectively. This means less show-and-tell presentations and more open, interactive, strategic discussions. It is only through greater focus and proactive setting of the board’s agenda that boards can discharge their responsibilities while more meaningfully influencing the company’s direction and results.

Other Interesting Points

- Expansion of earnings multiple. Companies usually focus on increasing their market capitalization by growing earnings. However, a result of transparency and sound governance can be the creation of shareholder value through growth of a company’s earnings multiple.

- Differing governance systems. In the Anglo-Saxon system, capital markets play a key role; in the German, Japanese, and European systems, banks play a more important role; in emerging markets, business groups are key. However, regardless of system and structure, the functions required for governance are the same.

- The Balanced Scorecard provides a framework to help organizations achieve better operating results, superior governance, and greater shareholder value.

The Balanced Scorecard has evolved based on the recognition that organizations create value for shareholders in several ways: 1) at the Strategic Business Unit (SBU) level, with emphasis on creation of a differentiated value proposition; 2) at the corporate level, through synergies and linkages based on corporate strategies; and 3) at the board level, by reducing the risk of a shareholder’s investment through transparency and governance.

The Balanced Scorecard helps organizations manage the value creation process at each of these levels. In each situation, the Balanced Scorecard creates a strategy map that links financial results with the key drivers of the business including customers, internal processes, and employees.

Enterprise Balanced Scorecard: The Enterprise Scorecard is the source of essential information for executive management and the board, providing a concise but thorough understanding of the business and its key drivers. This tool describes the company’s strategy, measures, and targets; identifies key processes, capabilities, and resources; and defines milestones and risks. Along with the Enterprise Scorecard, Enterprise Performance Reports (which make an appropriate first page in the board book) show the enterprise’s progress against the strategy.

Companies can create value based on excellence in governance.

Robert S. Kaplan

Board Balanced Scorecard: This tool adopts the Balanced Scorecard methodology and framework and clarifies specifically how the board intends to contribute to the organization. It provides clear statements about which entities (such as board committees or management) own specific results. The Board Scorecard details the tasks to be performed as part of the board’s basic mission, and includes activities such as: approve and monitor funding for strategic initiatives, evaluate and reward executive performance, and actively monitor risk and regulatory compliance. Part of the purpose of the Board Scorecard is to define the board’s informational needs so that it can complete board tasks. This Scorecard also includes self-assessment steps to monitor board composition and to evaluate board performance.

Executive Balanced Scorecard: Following development of the Enterprise and Board Scorecards, boards and management can work together to develop the Executive Scorecard. This helps specify expectations for senior management, define senior management priorities, and identify exactly how they will contribute to the organization. An example was provided of a financial institution where the top twelve executives had Executive Scorecards detailing their goals, measuring their contributions, and defining their priorities. Because Executive Scorecards state the exact role that managers are to play, they are useful in assessing the skills needed to fill open positions and as part of succession planning.

Biographies

Robert S. Kaplan is the Marvin Bower Professor of Leadership Development at Harvard Business School, and is a cofounder and chairman of Balanced Scorecard Collaborative, Inc. (BSCol). Prior to Harvard, Dr. Kaplan served as dean of the Graduate School of Industrial Administration, Carnegie Mellon University. Dr. Kaplan’s research, teaching, and consulting focus on performance measurement, including the Balanced Scorecard and activity-based costing. He is the creator of the Harvard Business School video series Measuring Corporate Performance. and the author of more than 100 papers and nine books. Dr. Kaplan received a BS and MS in electrical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a PhD in operations research from Cornell University.

Krishna G. Palepu is the Ross Graham Walker Professor of Business Administration and Senior Associate Dean, Director of Research, at the Harvard Business School. Professor Palepu’s research and teaching focuses on strategy, governance, and valuation in a global context. Prof. Palepu has written numerous articles and case studies on these subjects. Prof. Palepu is currently co-leading an HBS initiative on Corporate Governance, Leadership, and Values. Professor Palepu has a doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and an Honorary Doctorate from the Helsinki School of Economics and Business Administration.

Hollis Heimbouch, Program Host is Editorial Director of the Harvard Business School Press. She has acquired and edited books on strategy, technology, and innovation including The Social Life of Information. by John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid; The Monk and the Riddle. by Randy Komisar; and The Balanced Scorecard and The Strategy- Focused Organization. both by Robert Kaplan and David Norton. She is also a former Contributing Editor to Harvard Business Review. Previously, Heimbouch was Director of Editorial Development at Wired Ventures in San Francisco.