Biased financial advice is shockingly common but investors don t take the unbiased stuff

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

View full size AP Photo/Ben Margot The ups and down of financial advising: The Charles Schwab monitor reveals a negative Dow Jones Industrial at Schwab’s downtown financial district offices Thursday, March 22, 2001, in San Francisco. Schwab is cutting roughly 13 percent of their workforce, or approximately 3,400 people.

In recent decades, research has shown what Wall Street’s known all along: We are hazards to our own financial health.

We overestimate our abilities or chase the hottest trend. We fall prey to inaction, procrastination and information overload. Losses hurt a lot more than gains soothe.

Now, a flurry of research has emerged in the U.S. and Europe looking at whether financial advisers can help us overcome these pitfalls.

The results are not encouraging.

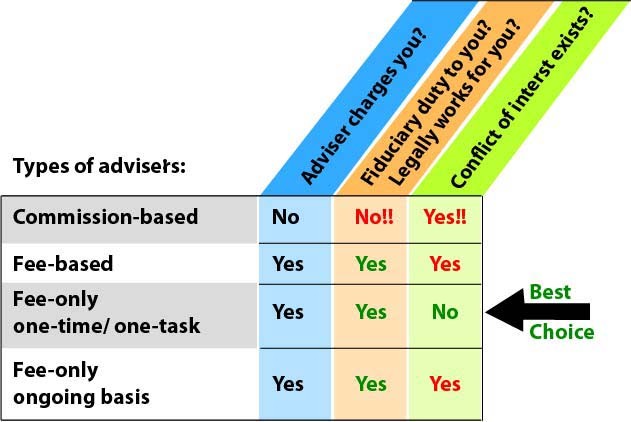

Tips for finding good financial advisers and planners

Advisers who get paid for the products they sell tend to harm their clients’ portfolios, two studies suggest. These advisers appear to make our biases worse.

Unbiased financial advice exists. But investors who need it most don’t seek it, a third study shows. Investors who do rarely follow it. And those who do follow it need the advice the least.

I’m not sure what to say about all this other than it’s time we all woke up. Regulators, employers and advisers can do more to protect our savings from biased money managers. But a whole lot of our success hinges on us.

How bad is general financial advice? Fairly bad and widely available, according to a study published in March by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

In the study, researchers from Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology sent secret shoppers to nearly 300 financial professionals around Boston. These trained financial auditors pretended to seek help improving their retirement portfolios.

Some of the mostly female shoppers told the advisers they wanted to invest in the best-performing funds. Others walked in with one-third of their investments in their own employer’s stock, another no-no.

A third group already held a portfolio of well-diversified, low-cost index funds, which research consistently shows to be the best way for average consumers to save for retirement.

The study doesn’t reveal where the advisers were employed other than to say banks, retail investment firms and independent shops. Most were paid on commission based on the fees and volumes they generate.

Initially, many advisers praised the shoppers’ portfolios, possibly to butter them up. But when they made recommendations, they favored funds with higher fees and commissions. In only 21 cases, about 7.5 percent of the time, did the advisers suggest index funds.

Worse, 85 percent of the shoppers with efficient, low-cost, passively managed investments were discouraged by the adviser from continuing with the strategy. Most were steered into higher-cost, actively managed funds. This was particularly true if the client was wealthy, where the fee income that would be generated for the firm would be higher.

Our evidence suggests that advisers’ self-interest plays an important role in providing advice that is not in the best interests of their clients, the authors wrote, adding that the market for advice works very imperfectly.

Advised clients had lower returns

Researchers from Goethe University got access to the performance of 37,000 investment accounts at a commercial bank and a brokerage. They compared the results of investors who made their choices with those who relied on advisers.

Advised clients had significantly lower annual returns: 8 percent versus 13 percent for those who invested on their own. They also owned riskier investments. And they traded more often, which generates more income for advisers and their employers but lower overall returns.

Our findings imply that many financial advisers end up collecting more in fees and commissions than any monetary value they add to the account, the authors wrote.

Surprisingly, those who relied on advisers were more likely to be richer, older, more experienced, self-employed, female investors rather than poorer, younger, inexperienced and male ones.

That led authors to liken these advisers to baby sitters.

Baby sitters, they said, are hired by well-to-do parents to perform a service parents can do better. They charge for it. But a child’s achievement is not boosted by baby sitters.

The investors, the authors concluded, were experienced but inattentive and failed to effectively monitor advisers and the outcome of their activities.

It’s buyer beware, right? If we’d just seek out financial advisers or planners who take no commissions — or turn a nanny cam on those who do — we’d be able to retire early.

Unfortunately, many of us seem both ignorant of these conflicts or eager to peer past them.

Remember those mystery Harvard/MIT shoppers? They expressed willingness to go back, with their own money, to nearly 70 percent of the advisers they visited, researchers found.

Free, unbiased advice has few takers

And if investors aren’t ignoring what they see, they seem tone-deaf to unbiased advice, if they seek it at all.

Don’t believe me? Get a load of this study. published in January in Oxford University’s The Review of Financial Studies.

Researchers worked with one of Germany’s largest brokerages in 2009 to offer 8,200 customers free advice for their self-directed portfolios. A computer program would produce the recommendations, with no commissions or other incentives tied to them.

All, it turns out, could’ve used some help. The customers’ returns, on average, significantly underperformed benchmark indexes.

Still, only 385 customers took advantage of the free offer. Of those, 260 failed to follow the advice. The 125 who did take the advice didn’t follow it very closely, and no one followed it perfectly.

And the 385 who accepted the offer were less likely to need advice. They were older, wealthier and more financially sophisticated than those who spurned it.

Had they followed the advice, their investments would have gained nearly 25 percent in the following six months, researchers found. Instead, those who made some changes logged, on average, a 21 percent gain. Those who made none gained 18 percent. Those who didn’t participate gained 17 percent.

Perhaps as important, the recommended portfolios would have been much less volatile, or risky. That’s a characteristic that gives investors more peace of mind.

When I asked this of the study’s lead-author, Utpal Bhattacharya, an associate professor of finance at Indiana University, he spoke bluntly: I don’t know that I can say anything positive.

Bottom line, he said, the government’s efforts to regulate biased advisers aren’t enough. We need to better educate consumers, too, to rid them of their biases.

Some of Bhattacharya’s colleagues in Germany are now researching the best ways to get investors to follow good financial advice.

Let’s hope they come up with something.

Until then, it’s time we bucked Wall Street and examined our own behavior. What kind of advice are we getting? How do we know it’s good? Are we willing to seek out, and pay, for unbiased advice? Will we follow it?

— Brent Hunsberger welcomes questions about his column or blog. Reach him at 503-221-8359. Follow It’s Only Money on Facebook. Google+ or Twitter.