Active ETFs Higher Cost V Value_1

Post on: 8 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Treasury Bond Supply and Demand under Fed Tapering (article )

June 2013

Many market participants expect Treasury bonds to collapse once the Fed ends its QE program because the Fed has been such a large buyer. However, I find that this scenario is highly unlikely: the combination of rapidly declining Federal deficits and persistently large purchases by the foreign official sector mean that the private sector will not have to start buying new long-term Treasury bonds even after the Fed ends QE.

When evaluating the impact of Treasury bond supply on long-term rates, most market observers seem to have overlooked two key issues: the large role of the foreign official sector (it is not all about the Fed), and the distinction between all Treasuries vs. only long-term Treasuries. Despite large issuance due to the $1.3 trillion federal budget deficit, private investors were actually net sellers of long-term Treasuries in 2011.

Journal of Alternative Investments. 2014, 17(2):9-24

On the surface, hedge funds seem to have much higher fees than actively managed mutual funds. However, the true cost of active management should be measured relative to the size of the active positions taken by a fund manager. A mutual fund combines active positions with a passive position in the benchmark index, which can make the active positions expensive. A hedge fund takes both long and short positions and uses leverage, which makes the active positions cheaper, but this can be offset by the expected incentive fees, especially for more volatile funds. We investigate the trade-offs from the perspective of a fund investor choosing between a mutual fund and a hedge fund, examining the impact of leverage, volatility, Active Share, nominal fees, and alpha for a realistic range of parameter estimates. Our calibration shows that a moderately skilled active manager is approximately equally attractive to investors as a mutual fund manager or as a hedge fund manager, showing that both investment vehicles can coexist as efficient alternatives to investors. Further, our model explains documented empirical findings on career development of successful fund managers and on hedge funds’ risk taking. Finally, we show that our findings are quite robust with respect to a jump risk in the hedge fund returns.

We investigate the return premium on stocks with high earnings quality using a broad and recent global dataset covering all developed markets from 7/1988 to 6/2012. We find that a simple strategy that is long stocks with high earnings quality and short stocks with low earnings quality produces a higher Sharpe ratio than the overall market or similar strategies betting on value or small stocks. This result holds both in the overall sample as well as in the more recent time period since 2005. Because the global earnings quality portfolio has a negative correlation with a value portfolio, an investor wishing to invest in both exposures can achieve significant diversification benefits.

Click here for data on Active Share of mutual funds

I sort domestic all-equity mutual funds into different categories of active management using Active Share and tracking error. I find that over my sample period until the end of 2009, the most active stock pickers have outperformed their benchmark indices even after fees and transaction costs. In contrast, closet indexers or funds focusing on factor bets have lost to their benchmarks after fees. The same long-term performance patterns held up over the 2008-2009 financial crisis, and they also hold within market cap styles. Closet indexing increases in volatile and bear markets and has become more popular after 2007. Cross-sectional dispersion in stock returns positively predicts average benchmark-adjusted performance by stock pickers.

Winner of the Commonfund Best Paper Prize at the EFA 2009 Annual Meeting

Winner of the Roger F. Murray Best Paper Prize (3rd place) at the Q-Group 2009 conference

Winner of Q-Group Research Grant 2007

NEW: Click here for return data on index-based factors

Standard Fama-French and Carhart models produce economically and statistically significant nonzero alphas even for passive benchmark indices such as the S&P 500 and Russell 2000. We find that these alphas primarily arise from the disproportionate weight the Fama-French factors place on small value stocks which have performed well, and from the CRSP value-weighted market index which is historically a downward-biased benchmark for U.S. stocks. We explore alternative ways to construct these factors and propose alternative models constructed from common and easily tradable benchmark indices. The index-based models outperform the standard models in common applications such as performance evaluation of mutual fund managers.

September 2009 (joint with Martijn Cremers) (published version ) (working paper )

Click here for data on Active Share of mutual funds

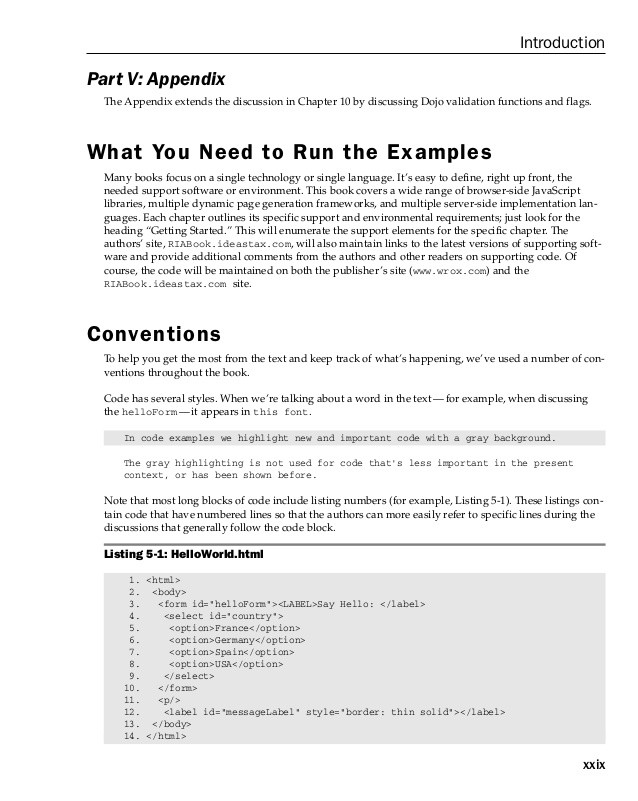

To quantify active portfolio management, we introduce a new measure we label Active Share. It describes the share of portfolio holdings that differ from the benchmark index. We determine the type of active management for a portfolio by measuring it in two dimensions using both Active Share and tracking error volatility. We apply this approach to the universe of all-equity mutual funds to characterize how much and what type of active management they practice. We test how active management is related to fund characteristics such as size, expenses, and turnover in the cross-section, and we examine the evolution of active management over time. Active management also predicts fund performance: funds with the highest Active Share significantly outperform their benchmark indexes both before and after expenses, and they exhibit strong performance persistence even after controlling for momentum. Non-index funds with the lowest Active Share underperform.

Keywords: Portfolio management, Active Share, tracking error, closet indexing

Why Do Demand Curves for Stocks Slope Down?

Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. 2009, 44(5):1013-1044 (lead article)

An earlier and more comprehensive version, including results on endogeneously arising institutions and optimal institutional structure (pdf file )

Separate appendices: Empirical tests (pdf file ) and a more elaborate model (pdf file )

Representative agent models are inconsistent with existing empirical evidence for steep demand curves for individual stocks. This paper resolves the puzzle by proposing that stock prices are instead set by two separate classes of investors. While the market portfolio is still priced by individual investors based on their collective risk aversion, those individual investors also delegate part of their wealth to active money managers who use that capital to price stocks in the cross-section. In equilibrium the fee charged by active managers has to equal the before-fee alpha they earn; this endogenously determines the amount of active capital and the slopes of demand curves. A calibration of the model reveals that demand curves can indeed be steep enough to match the magnitude of many empirical findings, including the price effects for stocks added to (or deleted from) the S&P 500 index.

The Index Premium and Its Hidden Cost for Index Funds

Journal of Empirical Finance. 2011, 18(2):271-288

This paper empirically investigates the index premium and its implications from 1990 to 2005. First, we find that the price impact has averaged +8.8% and +4.7% for additions to the S&P 500 and Russell 2000, respectively, and -15.1% and -4.6% for deletions. The premia have been growing over time, peaking in 2000, and declining since then. Second, the implied price elasticity of demand increases with firm size and decreases with idiosyncratic risk, supporting theoretical predictions. Third, we introduce a new concept that we label the index turnover cost, which represents a hidden cost borne by index funds (and the indexes themselves) due to the index premium. We illustrate this cost and estimate its lower bound as 21-28bp annually for the S&P 500 and 38-77bp annually for the Russell 2000.