Active ETFs

Post on: 14 Июль, 2015 No Comment

The credit crisis reaffirmed the idea that what begins in the US often ends up in Europe and, with our Eurozone crisis an added twist, the truism that when the US sneezes Europe catches a cold.

Flippancy aside, in the world of ETFs, the synthetic versus physical debate has been largely avoided in the US. with the March 2010 moratorium of the SEC on exemptive relief for ETFs wishing to make significant investments in derivatives.

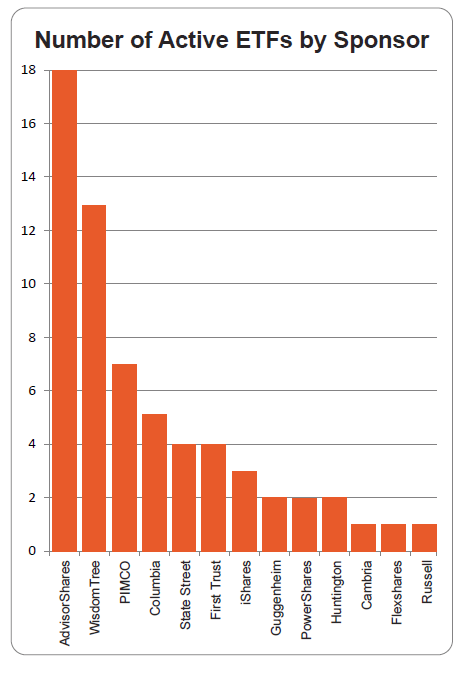

I suspect though the original pattern for ETF development in Europe to mirror the US will be repeated when it comes to so called active ETFs and the recent surge in filings in the US with over 20 recent filings with the SEC.

I have commented recently around the definition problems when it comes to active ETFs and the recent ESMA guidelines have been helpful in moving to clarify. They state it is an ETF “ the manager of which has discretion over the composition of its portfolio, subject to the stated investment objectives and policies (as opposed to a UCITS ETF which tracks an index and does not have such discretion). An actively managed UCITS ETF generally tries to outperform an index”. The guidelines go on to require promoters to make this fact clear in the prospectus, KIID and marketing documentation including “how it will meet the stated investment policy including, and where applicable its intention to outperform an index”.

On the face of it, these definitions leave open the possibility for a provider to bake an active methodology into an index which might range from a sampling strategy designed to outperform, to a more stock selective style screening methodology both of which strategies are already in use, particularly by fixed income funds.

The guidelines are quite prescriptive however on the use and construction of financial indices beyond the previous simpler formula that they be diversified, representative and published. Any index now ,that seeks to code an active strategy into an index will be forced to reveal the “secret sauce” in the requirement that the index constituents and their weightings must be published and freely available – a welcome requirement which even for some pure passive providers is going to raise some issues with the reluctant index provider.

It is the preservation of the “secret sauce” that raises some concerns around the question of ETFs that do not seek to replicate an index. I previously listed the characteristics of an ETF which included publishing an indicative NAV (iNAV) which lends itself to the liquidity of an ETF ensuring a tight spread of trading around the NAV.

The original ESMA consultation paper that lead to the guidelines suggested a requirement that the policy regard portfolio transparency be published with disclosure as to where this information and the iNAV “if applicable” is available. The Securities and Markets Stakeholder Group in their comments appeared to endorse that though were more bullish about an explicit statement stating it was not aiming to track an index. In the final guidelines however, ESMA noted that “some respondents questioned the merit and appropriateness of disclosing to investors how the iNAV is calculated as they will buy and sell units or shares at the offer price on the exchange.” The requirements as to iNAV therefore did not make the final guidelines even in the “if applicable” form.

This matters when we consider how the pricing of ETFs occurs and how it is kept in line with its NAV. Product structures who have looked at how to build a hedge fund ETF know that one of the issues that arise is the difficulty in selling a UCITS fund whose underlying constituents of the hedge fund index may not open as frequently as the ETF. This pricing disparity is reflected in the price and to be economic generally may require an in-house model where the swap provider, promoter and hedge fund index constituents are of the same group. Alternatively these hard to price models may operate a NAV+/- model where a spread for primary market creation is wrapped around the fund. Any profit or loss on this accrues to the fund with the managed hope it will balance over time.

Active funs being run on a vertically integrated model or through a non-transparent pricing model does not seem to be a progressive step and appears inconsistent with the transparency that underpins the original concept of an ETF.

The SEC in examining active fund filings will assess the ways in which a degree of transparency is introduced – be it full transparency in the hard to copy bond funds or proxy portfolios aiming to mimic the performance of the true underlying’s.

In Europe the promoters who might see a benefit in keeping the regulation on this small sector of the ETF industry high level would do well to reflect on a cautious approach to product development lest the simple message of ETFs that has lead to such growth compared to traditional mutual funds is undermined. The US ETF industry avoided the physical versus synthetic cold. An equally cautious approach to developing active ETFs is not without merit.