10 Tips to pick star fund managers and avoid lucky gamblers Citywire Money

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

F&C Investments’ Gary Potter and Legg Mason’s Wayne Lin explain how they select managers and what makes a star performer.

by Jennifer Hill on Oct 28, 2013 at 15:11

Studies have indicated that private investors often adopt a naive approach to determining a fund manager’s talents by focusing on past performance.

This approach tends to fail because outperforming managers generally underperform in subsequent periods.

Multi-managers, on the other hand – who run funds investing in other funds – try to figure out why a manager has outperformed and whether that is likely to be repeated.

How do they do this? We asked two multi-managers for their top five tips to determine skill.

When buying a fund, F&C’s multi-manager team recognises it is buying people, not objects.

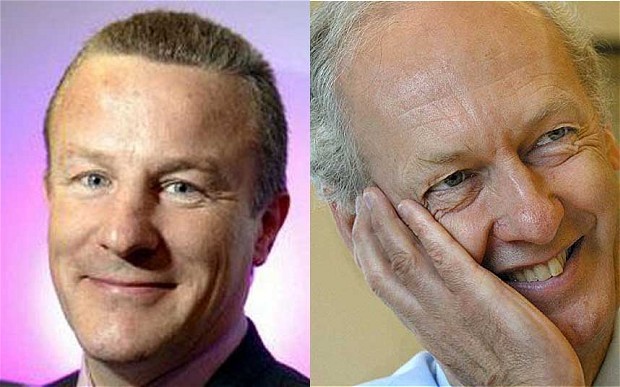

Gary Potter (pictured), co-head alongside Robert Burdett, said: ‘Selecting managers is all about using the science of investment analysis to support a view of an investment manager and team rather than letting the screening of performance data drive selection. Basing investment decisions only on the past is not likely to be a winning strategy.’

Which company does the manager work for? Is asset management crucial to the business? Does it have the right leaders? Are incentives in place to motivate the manager to deliver consistent sector-beating performance?

‘Culture is critical here, as is general corporate support for the manager or team,’ said Potter.

Other questions the F&C multi-manager seeks to answer are: what individual skill sets exist? Are there any deficiencies? Is the size of the team appropriate to the number of funds or mandates managed? And, crucially, has the team been stable and is it likely to continue to be so?

F&C also asks whether managers derive returns from stock selection or according to asset allocation driven by wider ‘macro’ factors. Are they long-term investors, riding out short-term volatility, or does a greater proportion of returns come from shorter-term trading? Where and how much risk is being taken? When do managers produce performance?

‘A fund might be producing higher returns, but is taking a lot more risk, so risk attribution is a critical assessment for us,’ said Potter.

‘Rarely is a manager both good at upside and downside capture; most will be good at outperforming in rising or falling markets, but rarely both.’

How many mandates or different funds is the manager responsible for? ‘However good a ship’s captain is, the bigger the boat you put him on, the harder he will find it to navigate tighter waters,’ said Potter.

‘We also rely very much on our dog-eared address book and contacts established in the industry over 20-plus years to get the heads up on potential new talent or where changes in a fund might make it a decent prospect,’ added Potter. ‘Conversely, we also need to watch for possible relative underperformance in a fund after a good run.’

Legg Mason’s approach in judging manager skill is based more on common sense than statistics. Wayne Lin (pictured), portfolio manager at Legg Mason Global Asset Allocation, said: ‘There is no magic statistic that can prove an investment manager has skill. ’

Good managers should be able to succinctly articulate their philosophy and provide analysis to support this.

‘If a manager believes that asymmetric information distribution leads to incorrect pricing in the market, he could produce a study of how long it takes for stock prices to react to earnings releases,’ said Lin.

‘The most important part of evaluating an investment philosophy is to make sure that it makes sense and it is possible to apply the investment philosophy to beat the market.’

How does a manager translate an investment philosophy into specific investment ideas? If the manager believes there is an information asymmetry in the market, do they subscribe to market data that will give them an information edge? How is this information edge used to determine which securities to buy and sell?

‘Every investment idea is not created equal: there may be some ideas in which the manager has more conviction,’ said Lin. ‘We seek to understand how all the ideas are generated and what determines the manager’s level of conviction for each.’

There are many different ways of constructing portfolios. Legg Mason tends to look for something that has been ‘well thought-out, but not over-engineered’.

This should be consistent with a manager’s investment philosophy. ‘Many quantitative managers believe that a disciplined approach to investing helps to overcome the human emotions of fear and greed,’ said Lin. ‘For these managers, we would expect to see a portfolio construction process that is heavily rules-based.’

Finally, Legg Mason looks for overall performance that is consistent with investment style. A value manager, for example, would be expected to underperform when growth is in favour.

Lin added: ‘We use performance information to validate the investment manager is fulfilling their mandate and not simply whether the manager is beating the market at that point in time. We tend to focus on three and five-year performance numbers because these are a better reflection of performance over a market cycle.’