What does the stronger dollar mean for commodity prices

Post on: 7 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Jonathan Humphrey — 15 December 2014

With the US dollar appreciating to levels not seen since the height of the Euro-zone sovereign debt crisis in 2010, CRU examines the relationship between the greenback and commodities prices.

The US dollar ceased to be commodity money in August 1971 when President Richard Nixon announced that the government would suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets. While this ‘temporary’ suspension means the greenback is no longer officially tied to the price of gold or any other commodity, a strong link still exists between commodity prices and the dollar’s value today.

Foreign demand wanes when the dollar rises…

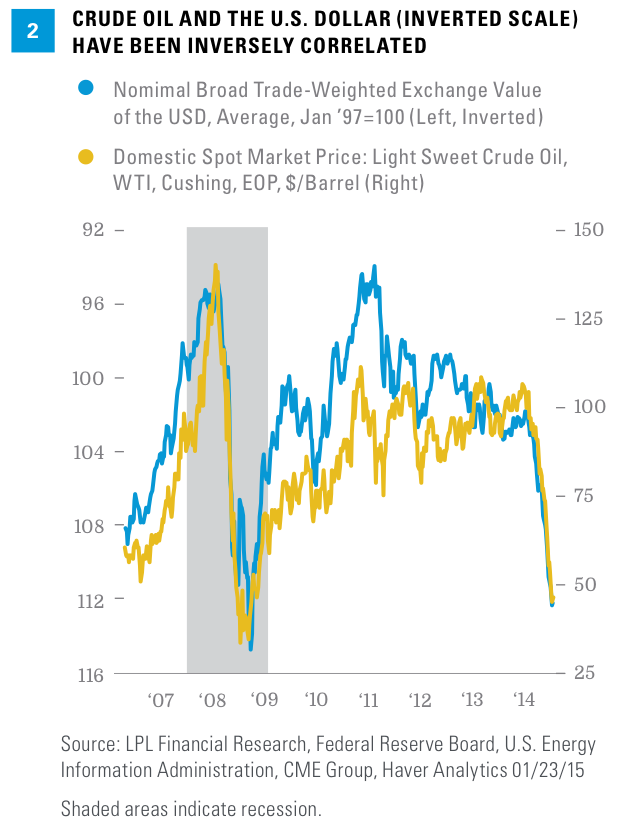

The relationship between dollar strength and dollar-denominated commodity prices is an inverse one for a number of reasons. When the dollar rises in value against other currencies, it makes dollar-denominated assets more expensive for consumers who operate using these other currencies which then weighs on demand. For instance, while the dollar price of zinc rose by only 1.5% between the end of July and November, dollar appreciation meant that German car parts manufacturers (for example) had to pay 15% more in euros for the same zinc.

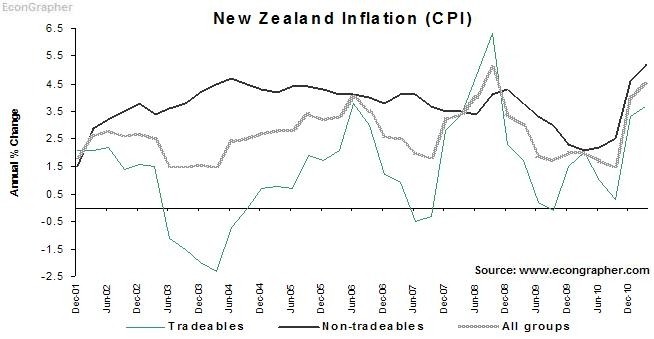

Affordability is not necessarily the only weight on demand. A weakening currency will typically cause a general increase in import prices in domestic currency terms. In response to this inflationary pressure an importing country’s central bank may tighten monetary policy which would reduce demand in the economy, including that for commodities.

…while there is incentive to increase supply

While a stronger dollar can dampen demand, it can incentivise producers to increase output. For, say, a copper miner in Chile, a US dollar appreciation against the Chilean peso can boost profit margins. All of the miner’s revenues will be received in US dollars, which will buy more pesos after the US$ appreciation, but some proportion of the costs will be denominated in pesos and will remain constant (at least in the short term). The prospect of a higher profit margin provides incentive to increase supply of copper.

While the impact of a stronger US dollar on both demand and supply may take some time to emerge, markets will price in looser global supply-demand balances relatively quickly, pushing down commodity prices in US dollar terms.

‘All generalisations are dangerous, even this one’

Of course, market dynamics differ for each commodity. As such, the extent to which a stronger dollar impacts a commodity’s price will vary. CRU offers three important considerations when reflecting on individual commodity markets in the face of dollar strength below.

Firstly, we should be careful in interpreting headlines regarding dollar appreciation. Much watched measures of dollar strength, such as the Federal Reserve’s trade weighted indices and the Dollar Index traded on the InterContinental Exchange, assign considerable weight to the US’s bigger trading partners.

Therefore, a significant portion of the dollar’s movements by these metrics are largely the result of changes in the dollar-euro exchange rate (especially in the case of the ICE dollar index) or the US dollar — Canadian dollar rate, the relevance of which will vary across commodities. Moreover, dollar gains can be suppressed (or not permitted) in countries with managed (fixed) exchange rates such as China. Understanding which currencies the dollar is moving against matters in commodity markets where the majority of buying and selling tends to be concentrated in certain regions. For example, between them South Africa and Russia account for some 88% of global platinum supply but their experience with the dollar has been quite different this year. While the trade weighted dollar has risen some 8% this year, one US dollar purchases 4% more South African Rand but 50% more Roubles over the same period.

In a similar manner, a second important consideration is the role of the United States in the market for a commodity. Markets in which there is a high proportion of US consumers see less depressed demand when the dollar strengthens as the exchange rate is not an immediate concern for US buyers. For instance we might consider, in the face of a stronger dollar, demand for coffee (a market in which the US accounts for some 25% of all imports) to hold up better than demand for rubber (a market in which the US consumes only a relatively small amount). Similarly, we might expect the supply response to be more muted if the US is a big producer (as it is in the market for soybeans for instance). Moreover, the same argument applies in the case of markets which involve much participation from China which manages moves in its currency relative to the US dollar; China typically accounts for 40-50% of global metals markets.

Thirdly, as the market price is set by the interaction of supply and demand, we should consider the extent to which these variables can change in response to dollar movements. Supply typically adjusts more quickly for soft commodities than metals as crops can be rotated more quickly than a mine can be brought online. On the demand side, we might expect more dollar-induced changes in a market for coffee (upon which Starbucks may depend but societies do not) than thermal coal as coal importers might reduce their demand to a point but then have to accept a perceivably higher price due to the financial and logistical challenges of switching energy sources.

Appreciating dollar horizons

The recent trend in the dollar has certainly been an upward one. Contrasting data releases which paint a more positive picture for the US economy next to those which have provoked more acute concerns for Europe, Japan and major developing nations have contributed to the broad dollar index’s 7% climb since late July.

Commodity market participants might well ask whether the dollar can continue to strengthen and provide yet more downward pressure on prices. CRU believes the dollar can and will continue to gain into 2015, albeit at a more modest pace.

One reason for this is US interest rates. During recent years, near-zero interest rates and three rounds of quantitative easing (which saw yields on the safest of investments held down) provided incentive for investors to sell the dollar and buy foreign assets which offered a higher return. With the Fed expected to raise interest rates next year (the median projection of the benchmark-rate setting committee is currently for an interest rate of 1.4% at the end of next year), dollar assets become more appealing to both domestic and foreign investors.

At the same time, solid gains in the labour market and the return of confidence amongst consumers and businesses all point to a rising tide in the United States. Difficulties in major economies across the Atlantic and the Pacific only accentuate the attractiveness of the US dollar.

Additionally, despite recent gains, the real value of the dollar is broadly undervalued according to the Federal Reserve’s trade-weighted indices. The real broad index is currently some 9% below its pre-crisis historical average which suggests the dollar is due a broad appreciation. Moreover, previous real appreciations of the dollar have tended to overshoot. While such periods have typically coincided with financial crises in other parts of the world (e.g. Latin American debt crises in the 1980s and Asian crises in the late 1990s) and CRU is not suggesting an appreciation of the broad dollar is necessarily a harbinger of crisis outside the US, CRU would not be surprised to see an appreciation of the dollar by more than is implied by its ‘fair’ value.

CRU currently sees the broad dollar index gaining a further 2% between Q4 2014 and Q4 2015 as consistent improvement in the US economy increasingly contrasts with data from much of the rest of the world. That said, an accelerated pickup in the economies of major US trading partners such as Mexico and interest rate hikes in others (appealing to carry traders) would offer potential for some downside risk to our dollar index forecasts. Nonetheless, when the US Federal Reserve starts to raise interest rates (CRU expects to see the first rate move in mid-2015), this will provide yet more of a tailwind to the dollar as investors have less incentive to look to assets in riskier foreign markets in the hunt for yield.

Headlines of the dollar’s strength should be interpreted with care as the implications of a stronger dollar can impact different markets in different ways. Clearly, the dollar exchange rate is not the only variable which can influence commodity prices and market prices will be shaped by prevailing economic conditions, market fundamentals and the decisions of financial market participants. However, given the influence the greenback can exert in the commodity markets, the potential for the dollar to not only maintain but also strengthen further into next year is negative for commodity prices.

For information on how CRU can help you understand the commodities markets through our suite of products and tailored solutions, please contact: sales@crugroup.com

Jonathan Humphrey | Economist

Jonathan joined CRU in February 2014 and is responsible for CRU’s coverage of macroeconomic and industrial sector developments in the Americas. He also is responsible for the development of econometric models used in CRU’s analysis work. Before joining CRU, Jonathan worked for the New York Stock Exchange group.

If you would like to receive these CRU Insights direct to your inbox for free, register here