The Plaza Accord The World Intervenes In Currency Markets_2

Post on: 10 Июль, 2015 No Comment

The ESF began to conduct foreign exchange market intervention transactions in 1934 and 1935. Also, it entered into credit arrangements, starting in 1936. From 1936 to the present, the ESF has participated in over a hundred credit or loan arrangements with foreign governments or central banks. After World War II, the ESF conducted Treasury’s monetary gold transactions and widened its participation in credit arrangements. Tables presenting data on all ESF intervention operations since 1973 and all ESF credit arrangements since 1936 can be accessed through the links above. Researchers should note that these data are for the ESF only and do not cover the operations of the Federal Reserve’s System Open Market Account (SOMA). Historically, U.S. intervention has been jointly financed by both the ESF and SOMA, and the financing has been equally shared between the two accounts.

Intervention Operations

Treasury policy during 1961-71 period focused on deterring capital outflows from the United States and giving major foreign central banks an incentive to hold dollar reserves rather than demand gold from the U.S. gold stock. The ESF resumed intervention operations in the foreign exchange market in March of 1961 (for the first time since the mid-1930s), but it soon became apparent that the resources of the ESF alone were too small to sustain transactions of the magnitude necessary. At the invitation of the Treasury, the Federal Reserve joined in foreign exchange operations in February 1962. The Federal Reserve entered into a network of swap agreements with other central banks [2] in order to obtain foreign currencies for short-term periods for use in absorbing forward sales of dollars by foreign central banks hedging exchange risk on their dollar holdings. To provide foreign currency to repay the Fed’s swap drawings, the Treasury during the 1960s issued non-marketable foreign currency-denominated medium-term securities (Roosa bonds) and sold the proceeds to the Fed.

In August 1971, the United States ceased conducting gold transactions with foreign monetary authorities, and the need to moderate the drain on the US gold stock was eliminated. In December 1974, ESF turned over, in a sale at par value, a gold balance of 2.02 million ounces (valued at $85 million) to the Treasury General Account. This gold had been acquired prior to August 1971 through gold transactions that the ESF engaged in with foreign monetary authorities and with the market for the purpose of stabilizing the value of the dollar relative to gold. In a public announcement of this sale of gold by the ESF to the Treasury General Account, the Treasury stated that the sale was made in view of the likelihood that the Exchange Stabilization Fund [would] not be engaging in further transactions to stabilize the value of the dollar relative to gold. [3]

Later in the 1970s, the US monetary authorities built up foreign currency reserves substantially. For this purpose, the ESF entered in a $1 billion swap agreement with the Bundesbank in January 1978 (which has since been allowed to expire). In connection with the dollar support program announced in November 1978, the Treasury issued foreign currency-denominated securities (Carter bonds) in the Swiss and German capital markets to acquire additional foreign currencies needed for sale in the market through the ESF. The United States also drew its reserve position in the IMF.

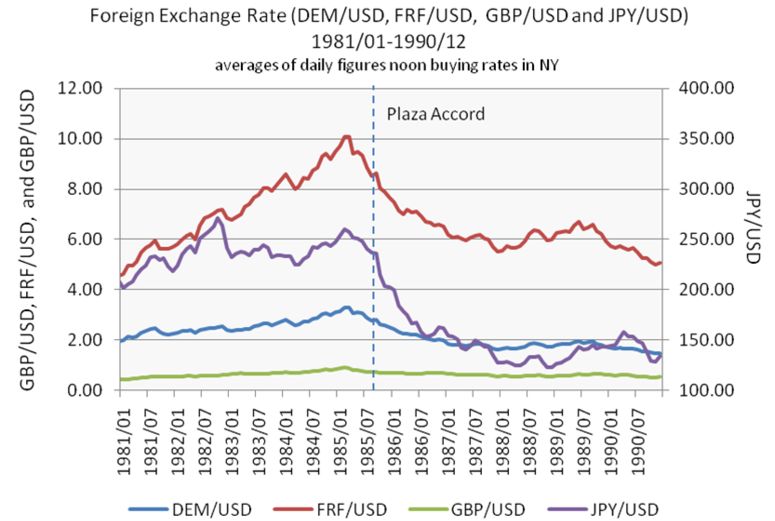

In the mid-1980s, the major industrial nations embarked on a process of intensified policy coordination. The Group of Five’s (G-5) Plaza Agreement in September 1985 served to reinforce exchange rate adjustments among the major currencies and occasioned substantial coordinated intervention sales of dollars. The G-5 agreed that exchange rates should play a role in adjusting external imbalances … should better reflect fundamentals … and that … some further orderly appreciation of non-dollar currencies against the dollar is desirable. In the Louvre Accord of February 1987, the major industrial countries agreed that the exchange rate changes since the Plaza Agreement would increasingly contribute to reducing external imbalances and … [had] brought their currencies within ranges broadly consistent with underlying economic fundamentals …[and] agreed to cooperate closely to foster stability of exchange rates around current levels. They adopted specific measures and cooperative arrangements reflecting their view that their currencies were broadly consistent with underlying economic fundamentals. This framework for cooperation on exchange rates complemented the broader economic policy coordination efforts to promote growth and external adjustment. In December 1987, the Group of Seven (G-7) reaffirmed Louvre’s basic objectives and policy directions and agreed to intensify their economic policy coordination efforts and to cooperate closely on exchange markets. There was continued active cooperation through late 1989, but such activities became less frequent thereafter and halted in mid-1990.

From the time of the Plaza Agreement until mid-1990, the U.S. monetary authorities were involved in episodes of net purchases of dollars vs. foreign currencies and episodes of net sales of dollars vs. foreign currencies. These operations were generally carried out in conjunction with operations by a number of other countries’ monetary authorities, including those of the major industrialized countries.

During 1993-1995, the U.S. monetary authorities again joined other monetary authorities in purchases of dollars vs. other major currencies. In one instance, this joint intervention was explicitly linked to a view among the G-7 countries that exchange rate movements had gone beyond levels justified by underlying economic conditions. In June 1998, the U.S. monetary authorities purchased yen in the context of Japan’s plans to strengthen its economy. In September 2000, the U.S. authorities bought euros in a coordinated intervention operation that the European Central Bank initiated out of concern about the potential implications of euro exchange rate movements for the world economy.

The ESF has a long history of credit operations beginning in the early years of its existence. In connection with these operations, the ESF had a large number of swap lines after World War II, primarily with Latin American countries, but these were gradually eliminated. By 1970, only a swap line with Mexico remained and, in 1994, this swap line was brought under the North American Framework Agreement, which also covers Federal Reserve and Bank of Canada swap lines with Mexico. Starting in the mid-1970s, ESF credit operations arrangements have for the most part involved ad hoc swap agreements rather than standing swap lines.

The tables accessible through the “Credit Operations” link above show ESF credit arrangements that entered into force from 1936 to 2002 and provide a brief description of each. In addition to the arrangements listed here, Treasury extended to the United Kingdom an overnight credit in September 1967 and a $200 million line of credit in March 1968, both as part of multilateral operations to support the pound sterling in the foreign exchange market.

[2] The Federal Reserve eliminated almost all of its swap lines after years of disuse and in connection with the advent of the European Central Bank on January 1, 2000 and now has swap lines only with Mexico and Canada under the 1994 North American Framework Agreement.

[3] The ESF again had gold on its books for a short period in 1978 as a counterpart to an ESF credit to Portugal.