The Ethanol Industry An InDepth Primer

Post on: 8 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Summary

- The ethanol industry has historically been overshadowed by oil and gas and by other alternative energies.

- It achieved outstanding performance recently and delivered outsized equity returns.

- Conditions are and will remain favorable for ethanol production at least in the short run.

- There is still much value in ethanol to be seized by informed investors.

- This article serves to provide you with the tools and metrics to better find value in this industry.

As a summer of studying and working in the ethanol industry comes to an end, I have decided to share a bit of what I learned the last few months.

The ethanol industry is a sector historically overshadowed by the oil & gas industry and by other alternative energies. After a recent few years in distress, it has become very profitable of late, rewarding astute and informed investors with outsized returns. Just look at the recent performance of Pacific Ethanol (NASDAQ:PEIX ), Green Plains Renewable Energy (NASDAQ:GPRE ), and REX American Resources Corporation (NYSE:REX ) as examples. I believe this run will continue in the short to medium term, and with history’s tendency to repeat itself, no doubt a similar sequence of conditions will present itself again in the long term. Hence, the purpose of this primer, if you will, is to inform to the best of my ability so that you may be better armed with the adequate tools and knowledge, and with these, make educated investment decisions to partake in the great wealth generated by the ethanol industry.

First, I will provide an overview of ethanol industry and the various factors affecting its supply, its demand, and its viability. Next, we will explore the current landscape and identify the key players in the industry. Later, we will study the ethanol production procedure step-by-step to elucidate the cogs and gears involved. Armed with this understanding, we will then identify key metrics and drivers to better judge the profitability and determine the valuation of an ethanol producer. Finally, I will provide thoughts on potential risks, upcoming catalysts, and predictions for the industry moving forward, and end with actions you can take with your investments.

Industry Overview

Ethanol, in the context of transportation, is a biofuel at the present primary derived from corn, but can also be produced from sugar cane, soybeans, and other plant material. Its use as an additive to conventional gasoline was sparked, if you would excuse the pun, by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) instatement of the Clean Air Act and subsequent laws to control air pollution by mandating cleaner-burning additives, such as ethanol, to be mixed with gasoline. Coupled with the controversy over a competing additive (MTBE) and with world energy shortages looming, the domestic ethanol market has been able to grow to the roughly $50 billion industry it is today, capable of producing nearly 15 billion gallons per year (BGPY). Much of its viability however is still dependent on federal and state regulations which will be discussed in later sections.

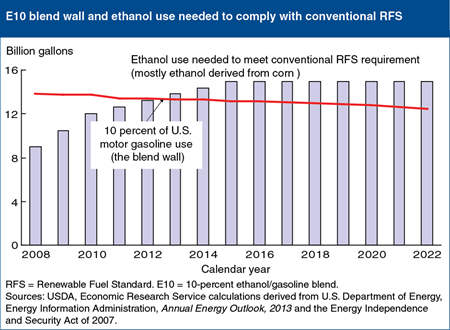

Currently, more than 90% of gasoline sold in the U.S. is blended as E10 — the term for fuel mixture consisting of 10% ethanol and 90% gasoline, which has historically been the limit for fuel to be considered substantially similar to gasoline by EPA definitions. Refiners can increase the ethanol blend at their discretion. However many argue against the practice, citing consumers’ reluctance towards, and automakers’ caution of, higher blends and their repercussions on engine integrity. This adversity to discretionary blending creates an important phenomenon in the industry referred to as the Blend Wall, a ceiling of sorts to ethanol demand that puts downward pressure on ethanol prices as supply nears about 10% of motor gasoline consumption.

Source: Graph produced by author, with underlying data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration .

To make matters more interesting, a pivotal catalyst in the ethanol industry came in 2005 when the EPA created the Renewable Fuels Standard program. The program mandated minimum volumes of renewable fuels to be blended in the U.S. The program was later revised and expanded as RFS2 in 2007; it outlines now year-by-year volume targets for each category of renewable fuel-cellulosic ethanol, biomass-based diesel, and conventional corn-based ethanol-to an ending cumulative target of 36 billion gallons by 2022.

This program has met with resistance from the oil industry, understandably so because ethanol can be considered to compete with the black gold. In fact, many refiners have been accused of quietly refusing to invest in the infrastructure and technology to accommodate for increased renewable fuels consumption. As a result of this perhaps stifled ethanol adoption, the mandated blending volume for corn-based ethanol exceeded the Blend Wall in 2013, causing refiners to struggle to satisfy their quotas, often at significant costs. Opponents of RFS2 now are using that aforementioned reason to push to lower mandated blending, to freeze the program, and even to scrap it altogether.

One way refiners can satisfy the rest of their quota is by purchasing Renewable Identification Numbers, or RINs. RINs are 38 digit numbers generated by ethanol producers whenever a gallon of qualified renewable fuel is produced: 1 RIN for a gallon of corn-based ethanol, 1.5 RINs for a gallon of biodiesel, and 2.5 RINs for a gallon of cellulosic biofuel, with the number of RINs generated reflecting the energy equivalence value of the respective fuel. The purpose of these RINs is to track renewable fuel production and consumption and to ensure that refiners are indeed meeting their quotas. When biofuel is sold, its attached RINs are transferred to the refiner who can retire them to show compliance with regulations or separate them to sell within a year to other refiners to show compliance.

The ability of RINs to be transferred like a commodity creates a secondary market in the ethanol industry. Refiners who have blended more than their required 10% quota can sell their excess RINs to other refiners; hence, it is possible for refiners to blend less than 10% ethanol yet still remain in compliance. Generally, the price of RINs moves opposite to the gasoline-ethanol spread; when ethanol per gallon prices are higher than gasoline per gallon prices, refiners are more inclined to buy RINs instead of physically blending ethanol, and vice versa, to satisfy their quotas. Recently however, much speculation has entered the RIN market, driving up prices. Traders try to predict the Blend Wall-RFS2 volume difference with the knowledge that the smaller the difference, especially if negative, refiners will be pressured to purchase RINs to meet their quotas, driving up RIN prices. There are many more complexities with the RIN market, such as a price hierarchy depending on which type of renewable fuel the RINs came from, as different fuels satisfy a different set of renewable fuel requirements. That level of understanding though is beyond this article.

Source: Graph produced by author, with underlying data from the US Department of Agriculture .

Aside from RINs, refiners can also choose to discretionarily blend past E10 to fulfill their quotas. The EPA has been issuing partial waivers for E15, now approved for use in light-duty motor vehicles with model years 2001 and newer. However, as mentioned before, there currently lacks the infrastructure on both the refiners’ and automakers’ end to accommodate widespread use of E15. Because higher blends are more corrosive, E15 blends require specialized transportation and storage mediums in which refiners have largely been slow to invest. Automobile manufacturers’ practice of voiding warranties on vehicles pumped with E15 fuel is also a roadblock to the widespread adoption of E15. Other than E15, another typical ethanol blend is E85, which is a bit of a misnomer because it can refer to blends from 51% to 85%. The flex-fuel vehicles that use this blend may have problems starting, especially in severely cold climates; back-up mechanisms using gasoline for engine ignition are often built in. As a result, in addition to the lack of infrastructure support for E85, flex-fuel vehicles are relatively unknown in the U.S. In fact, a recent GM study showed that 70% of owners of its flex-fuel vehicles were unaware they owned a flex-fuel car.

The discussion on E85 and flex-fuel vehicles serves as a perfect segue to another large swing factor in ethanol demand past the Blend Wall: global trade. Currently, Brazil together with the U.S. dominates production and consumption in this space. However, Brazil has a much more efficient and favorable environment for the use of ethanol as transportation fuel. Since 2007, E25 has been mandatory there; the widespread flex-fuel vehicles in Brazil have even been built to run on E100 blends as well. As a result, Brazil has been a key ethanol importer of U.S. ethanol. This relationship is mutual; U.S. is also a key ethanol importer of Brazilian ethanol, especially when Brazilian prices become more competitive than domestic ones. Because of the Blend Wall and other limitations, a positive trade balance is the major variable demand factor for domestic ethanol.

In addition to international factors, domestic government incentives, like the Blender’s Tax Credit (BTC), could also drive ethanol demand in the U.S. The last ethanol blender’s tax credit, called the Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit (VEETC), was cancelled in 2011. While it was active, it gave a fixed $0.45 federal tax credit to blenders for every gallon of ethanol blended with gasoline. If a program like this is passed again in the future, blenders would be incentivized to embrace higher blends if the economics work, potentially driving up the Blend Wall and ethanol demand.

Current Landscape

Currently there are 211 plants in the U.S. capable of producing a total of almost 15 BGPY. Most plants are located in the Midwest, as seen in the map below, where there are much more favorable corn bases due to the proximity to corn supply. The plants range widely in size, with large plants capable of pumping out more than 100 MGPY compared to smaller plants’ sub-40 MGPY.

Source: Renewable Fuels Association.

The space is dominated mainly by large consolidated players such as Archer Daniels Midland, (POET), Valero, (GPRE), and others, which make up about 60% of total production. Because they operate on large scales and employ some of the most cutting-edge technology, they typically command more favorable prices and higher operational efficiency and profitability; and their margins are generally less volatile due to their advanced risk management solutions to hedge commodity prices. As a result, the first batch of ethanol demand is typically filled by these suppliers. Smaller players then supply the remaining portion of ethanol demand. During times of depressed ethanol demand then, it is generally the smaller, marginal players that are forced to idle their plants while large integrated players remain operational albeit at lower margins. During times of profitability such as now, the sector largely becomes a buyers’ market with everyone trying to acquire additional capacity, consolidating the industry.

Ethanol Production Process

Most of the ethanol today is produced from corn, and predominantly via one of two processes: wet mill and dry mill. The dry mill process involves grinding the corn and introducing water to the meal to form a mash. Enzymes are then added to the mash to convert the complex starch into more simple sugars such as dextrose. The resulting solution is then ready for the fermentation stage during which yeast converts the sugars to ethanol and CO2; because the yeast functions optimally within a very specific pH range, ammonia is often used to control acidity levels. The product of the fermentation, termed beer, contains a mix of ethanol and residual stillage. To separate the two, the mixture is transferred to a distillation tower where the former is distilled and passed through a molecular sieve to near 100% alcohol levels; it is then blended with the industry standard of about 2.46% denaturant, usually gasoline, and stored to be shipped to market. The residual stillage however requires further processing to extract value. The liquid portion of the stillage is boiled to increase dissolved solids concentration to produce syrup, which is then mixed with the coarse grain portion of the stillage to produce wet distiller grains WDGs. WDGs can then be sold as is or dried in a process that requires a significant amount of natural gas and sold as dried distiller grains DDGs. Both serve as high-protein animal feeds.

In the dry mill process, corn in its entirety is grounded and used as the initial ingredient and only later during distillation are distinct components separated. In contrast, the wet mill process seeks to extract the highest use and value out of each component of the corn kernel. As a result, it involves breaking down the corn first into the bran, the germ, and the endosperm before processing each part into its final product: the bran to distiller grains, the germ to corn oil, and the endosperm to ethanol. The first two are not very relevant, so we will focus our attention on the distinguishing characteristics of the third.

The starch mixed with gluten that makes up the endosperm cannot yet be processed by yeast to create ethanol. Before that, the mixture first enters the slurry mix tank where alpha amylase enzymes and hot water are added, the mixture heated, cooled, then pumped into liquefaction tanks where alpha amylase work their magic to simplify the complex starch and reduce mash viscosity. During this process, pH levels must stay around 7, with the help of sulfuric acid and sodium hydroxide, to ensure optimal results. The liquefied mash then undergoes saccharification during which glucoamylase (NYSE:GA ) enzymes further breaks down the sugars into fermentable glucose, which is then converted into ethanol via fermentation with yeast; as in the dry mill process, CO2 is also produced, which should be scrubbed for vaporized ethanol suspended in the CO2 before being vented into the atmosphere. The remaining steps are similar to those of the dry mill process after fermentation, namely separating the traces of protein and the ethanol-water via distillation and further processing each.

Source: Renewable Fuels Association.

Each process has its own advantages and disadvantages. The dry mill process focuses on the production of corn ethanol and as a result, it is much less capital intensive. The downside then, as hinted, is that it is limited to producing only a few products from the processing of corn; and the co-products are generally of lower quality. The wet mill process involves much more capital and a larger investment. However, the fruit of this additional cost is versatility and the ability to produce significant amounts of co-products of high purity: corn oil, gluten meal, corn syrup, in addition to what comes out of the dry mill process. In the end, a plant’s decision to choose one or the other is largely dependent on local demand for those additional products as well as adequate monetary and human capital.

Drivers and Relevant Metrics

The corn-based ethanol production process itself already reveals several main cost and revenue drivers in the sector. Aside from the obvious factor of ethanol prices, the largest determinant of profitability in the industry is feedstock costs; continuing with our focus on corn-based ethanol, this is generally calculated as the CBOT corn futures plus the corn basis, which accounts for transportation and other handling costs of bringing the corn to the plant. Needless to say, the farther away a plant is from where all the corn is being harvested-namely Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa-the higher the corn basis. A major viability metric used for ethanol producers then is the corn crush spread, typically defined as the price spread between 2.8 gallons of ethanol and the industry standard amount of corn used to produce it, one bushel. As seen in the chart below, crush margins were severely depressed in 2012 and part of 2013, which forced many plants to idle their operations. In the past year however, crush margins have improved dramatically with the help of near-record low corn prices. Such favorable conditions have allowed ethanol plants to report elevated earnings and to award astounding equity returns.

Source: Graph produced by author, with underlying data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture .

Other costs in the production process include the cost of denaturant, enzymes, and ammonia, simplified to $/gal ethanol produced, natural gas in $/mmBTU, air and water permit costs, and transportation costs, which plants can mitigate by locating themselves near a major railroad such as the BNSF and the Union Pacific. In addition, because of the chemically-intensive nature of the wet mill process, the cost of chemicals and microbes, again measured in $/gal ethanol, can also be significant, especially GA enzymes. There is a large market that provides solutions to help mitigate these costs however. Mascoma/Lallemand, Lesaffre, Verenium, Dupont/Genencor, and Novozymes all provide bioengineered solutions to increase efficiency and reduce required usage quantities. An innovative solution to note is the creation of a yeast that can perform simultaneous saccharification and fermentation, removing the need for expensive GA enzymes.

Other revenue drivers include the price of distiller grains and that of corn oil, both of which closely track corn prices. It may be useful to note that the price of WDGs is lower than that of DDGs to reflect the additional natural gas needed to dry former as well as latter’s relative ease of transport and longer shelf life. Plants take into account local demand for farm feed as well as distance to the demand when deciding whether it is worthwhile to dry their WDGs.

Combining the cost and revenue drivers into a single profitability metric is the measure of EBITDA per gallon ethanol sold. The top few ethanol plants typically operate above $0.30/gallon ethanol produced. A ratio above $0.25/gal is typically considered sustainable; anything between $0.10/gal and $0.25/gal, temporarily sustainable, and anything below, unsustainable. In corroboration with previous statements, you can see in the chart below operating margins dropped well below the unsustainable threshold in 2012 and part of 2013; they later recovered in 2014 with the help of favorable crush spreads, allowing producers to enjoy outsized returns.

Source: Graph produced by author, with underlying data from the Center for Agricultural and Rural Development .

Finally, enterprise value per gallon ethanol sold is another important valuation metric in the industry. The general rule of thumb is a buck a gallon for a functional plant during favorable conditions. Exceptions are times of distress, when you can see plants selling for 30 or 40 cents on the dollar, and publicly traded companies, which enjoy higher valuation due to higher liquidity, the lack of which is a major problem for private players. More detailed examinations of EV/gal ratios will follow in subsequent articles.

Looking Forward

Hopefully, this article has by now provided you with a better understanding of the workings of the ethanol market. As explained above, there are a myriad of factors driving the future of this industry: the corn crush spread, gasoline prices and consumption, the adoption of E15 and E85 blends, global demand, the RIN market, and regulatory catalysts such as RFS2.

First, the corn crush spread. Currently the crush spread is still quite accommodating to producers in the sector. While this has been a boon to increasing profitability in the ethanol industry, it may also be its bane. More and more capacity is being resumed or constructed, and we are also starting to see large refiners such as Valero (NYSE:VLO ) invest in producing ethanol in-house. Such trends foreshadow a glut of ethanol supply if future regulations or mindsets do not become more accommodating. A potential offsetting factor is the general consensus that corn prices will remain depressed well into 2015 because of large corn inventories and higher corn supply from improved harvesting technology among many; and even after, they are expected to remain between the $4-$5/bu range. I will leave you with these observations and refrain from any predictions.

Similarly, it would be brash to assume I can speak about future gasoline prices with any certainty. Motor gasoline consumption however has shown a clear decline over the recent years. This has important consequences for the ethanol industry because of the Blend Wall phenomenon. If this trend were to continue, ceteris paribus, we can expect to see a decline in ethanol demand.

Source: Federation of American Scientists.

Two solutions to lowered ethanol demand due to decreasing gasoline consumption are the adoption of higher blends and increased global demand. The former is gaining more traction as more and more gas stations are beginning to provide E15 and E85 blends; support among car manufacturers is also growing, led by GM. The latter is also highly likely. China is beginning to embrace ethanol as an alternative fuel source, driven by the need to put to use its large grain surpluses. In addition, the lowering U.S. ethanol prices due to domestic oversupply make American ethanol more competitive to Brazilian ethanol, hence increasing ethanol exports. Another offsetting effect of lowered ethanol prices is that it creates an environment that is favorable for refiners to blend ethanol rather than purchase RINs. We can then expect refiners to be more inclined to blend ethanol at least in the short term.

Finally, as the industry is still very much reliant on government regulations and incentive systems, the future of RFS2 will greatly influence the viability on the industry, at least in the short-to-mid term. Currently, the RFS2 has not been finalized for 2014, casting much uncertainty about their continuance. The former has proposed a preliminary mandate of 12.2 billion gallons of conventional ethanol, which represents a reduction of the 14.4 billion gallons originally drafted. This could be a sign that original targets are too ambitious which, together with significant opposition to the program and lack of adequate infrastructure and technology, is forcing the EPA to scale back on those targets. A counter argument however is that because soon an increasing portion of the total renewable fuels quota is to consist of non-conventional (non-corn-based) ethanol, and because the technology for such advanced biofuels production is still in its infancy, resources will shift to stimulating corn ethanol production and blending instead. The beginnings of this can be seen in the 2014 proposed mandate in which the cellulosic biofuel target is a mere 17 million gallons, or 1% of the originally proposed 1.75 billion gallons in 2014. Whether or not this reduced volume will roll over for conventional ethanol to fulfill is up for speculation.

Investment Actions

Taking into account all the factors in the previous section, I will not be surprised to see signs of a 2012-like downturn next year. In the meantime however, the ethanol industry is still alive and kicking, and there is still much value to be realized. Just look at REX’s recent quarterly earnings release, in which diluted EPS of $2.68 beat estimates by $0.63 and last quarter’s number by $0.01. Its stock jumped 20% since then from $90 to $108 at the moment.

Hence, keep holding the ethanol players in your portfolio if you have any, but keep a wary eye on market conditions, especially further news on crush spreads or government regulations. If you are feeling speculative and want to bet on a favorable RFS2 ruling, GPRE and PEIX are the better plays right now, which are just waiting to spike at the news. You can also capture some upside while limiting your downside with VLO, whose price cut last month makes it a good investment regardless of its ethanol capabilities.

The fundamentals and valuation of these companies, not just the short-term market catalysts, will be explored in depth in subsequent articles.

Disclosure: The author is long PEIX, REX, VLO. (More. ) The author wrote this article themselves, and it expresses their own opinions. The author is not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). The author has no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.