Precious metals not always golden

Post on: 2 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

At Manfra Tordella & Brookes, the upscale gold dealer in New York, business is brisk. Today, I sold a lot of gold, sales director David Phillips said this week. I also bought a lot of gold. The U.S. mint is selling a lot of gold, too. The mint sold 49,000 gold eagle bullion coins in February, compared with 9,500 a year earlier.

In fact, as gold hovers near $1,000 an ounce, the whole nation seems to be trading gold. It’s hot, says Eric Vallow, manager of Lev’s Pawn Shop in Fort Wayne, Ind. People are bringing in gold jewelry and coins to sell, Vallow says. And on days when gold takes a tumble, as it did Wednesday and Thursday, he’s happy to buy.

Given the huge surge in gold prices, a logical question is: Should you be a buyer? The answer: Yes, but not much, and not right away.

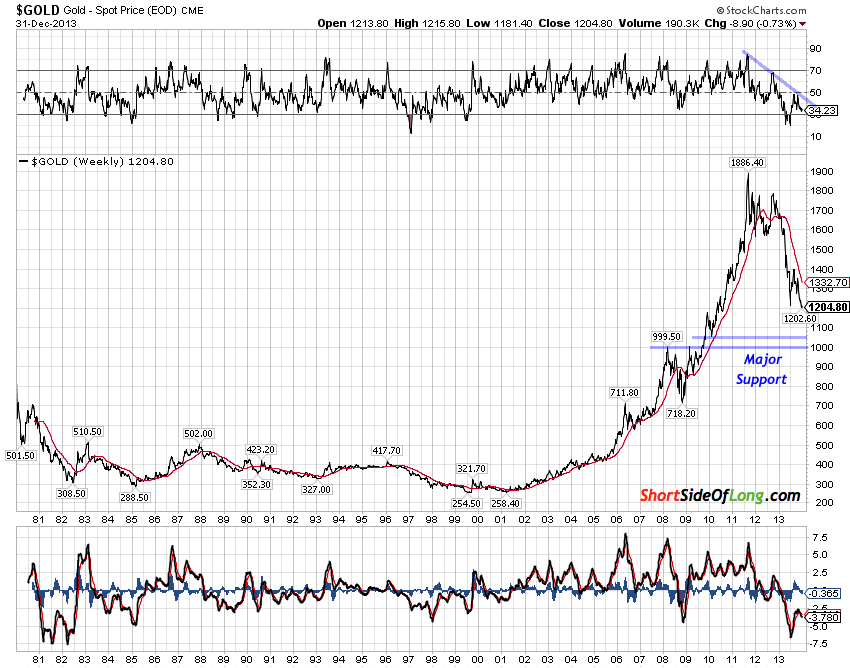

Gold prices bottomed in April 2001 at $255.95 an ounce. They’ve more or less marched steadily upward since then. At Thursday’s close of $975 an ounce, gold has gained $719.05, or 281 percent, from its 2001 low.

Life hasn’t always been so good for gold aficionados. Gold peaked at $850 an ounce in January 1980. Adjusted for inflation, gold would have to hit $2,144 an ounce to match its 1980 peak.

And that’s one argument for buying gold, which is a hedge against inflation. As the value of paper money deteriorates, the value of gold rises, because gold tends to keep its buying power in times of inflation and economic uncertainty. If the price of gold were to catch up to inflation, it still has a 100 percent move in front of it.

Bear in mind, though, that the $850 peak in 1980 was a classic speculative blow-off top: Gold had soared 66 percent in just 14 trading days. The $850 gold price was available for just one frenetic trading day. The average price of gold during 1980 was $613, according to gold bullion dealer Kitco. If we use that as a slightly more rational starting point, gold would need to hit $1,570 an ounce to equal its 1980 level — still a colossal gain.

But perhaps inflation parity isn’t a good reason to buy gold, anyway. Gold averaged $307 an ounce in 1979, just one year before the 1980 peak. Using that as our benchmark, gold already has caught up with inflation: The inflation-adjusted equivalent of $307 in 1979 is $893 in today’s dollars, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But there are reasonable long-term arguments for gold:

Inflation. Gold tumbled from 1980 through 2001, in part because inflation was low, and people eventually stopped worrying about it. But people are fearing inflation now: The price of oil has risen above $100, for example, and the price of wheat has leaped to $11.27 a bushel from $4.74 a year ago. Though the government’s consumer price index has gained 4.3 percent since January 2007, big price jumps in everyday items can spark an inflationary mind-set. That’s good for gold.

The dollar. Gold moves in the opposite direction of the dollar, and the dollar has been on a toboggan run downhill the past 12 months. A euro now is worth $1.54, versus $1.31 a year ago.

The debt. The United States has $9.4 trillion in debt outstanding, equal to about 67 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product. In 1980, federal debt was equal to 33 percent of GDP. Some argue that the government eventually will succumb to the temptation to get out of debt by printing more money, which is inflationary.

Supply. Should someone find a gargantuan new gold field, then the price of gold (all things being equal) would tumble. If someone has struck gold, he or she hasn’t told anyone. And even if someone does find a gold vein, it takes years to open a new gold mine.

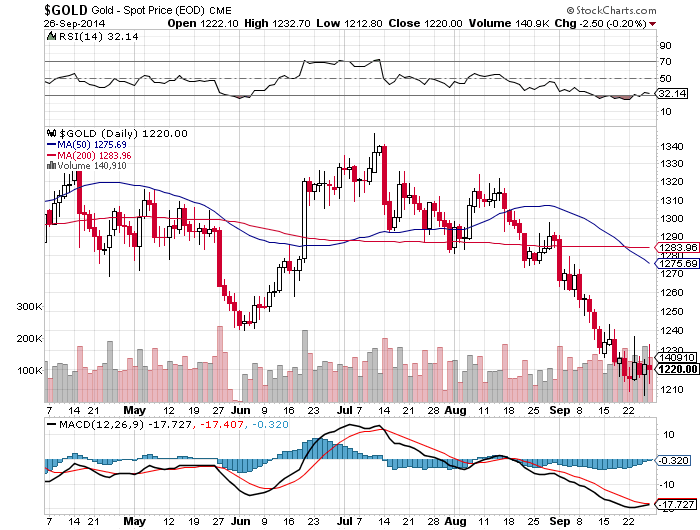

If the long-term argument for gold is a reasonable one, the short-term argument isn’t quite as strong, says John Derrick, director of research at U.S. Global Investors, a fund company. In the short term, we’re due for a correction, he says.

The main reason: Barring a 1980-style blow-off, the price of gold is up too far, too fast. We’ve moved a fairly large amount in a quick period of time, and history tells us we’re due to correct, Derrick says. He thinks a drop to about $910 or so is possible, so if you’re considering investing in gold, you might have some time to think about it.

Start by thinking about how you’ll invest in gold. If you want to buy the metal itself, gold bullion coins, such as the U.S. Eagle or the Canadian Maple Leaf, are good bets. Avoid rare gold coins, because their value is pegged, in part, to their scarcity and condition.

The problem with gold coins is that they can be lost or stolen. If that worries you, consider investing in the StreetTracks Gold Shares Fund, which invests in gold bullion. One share equals about one-tenth the price of an ounce of gold. You also might consider investing in a gold mutual fund, which typically buys the shares of gold-mining stocks. The top five funds are in the chart.

But the big problem with gold and gold funds is they can be insanely volatile. If you make a big bet on gold, be prepared to take a big loss. You really shouldn’t keep more than 5 percent of your portfolio in gold, and you should rebalance regularly. If your holdings grow to 10 percent, sell enough to get back to 5 percent. If they shrink to 2 percent, buy enough to fill your holdings to 5 percent. You’ll be selling high and buying low — and that, at least, will help you keep some of the gold you gain.