How Unions Work

Post on: 3 Июль, 2015 No Comment

What Unions Do: How Labor Unions Affect Jobs and the Economy

What do unions do? The AFL-CIO argues that unions offer a pathway to higher wages and prosperity for the middle class. Critics point to the collapse of many highly unionized domestic industries and argue that unions harm the economy. To whom should policymakers listen? What unions do has been studied extensively by economists, and a broad survey of academic studies shows that while unions can sometimes achieve benefits for their members, they harm the overall economy.

Unions function as labor cartels. A labor cartel restricts the number of workers in a company or industry to drive up the remaining workers’ wages, just as the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) attempts to cut the supply of oil to raise its price. Companies pass on those higher wages to consumers through higher prices, and often they also earn lower profits. Economic research finds that unions benefit their members but hurt consumers generally, and especially workers who are denied job opportunities.

The average union member earns more than the average non-union worker. However, that does not mean that expanding union membership will raise wages: Few workers who join a union today get a pay raise. What explains these apparently contradictory findings? The economy has become more competitive over the past generation. Companies have less power to pass price increases on to consumers without going out of business. Consequently, unions do not negotiate higher wages for many newly organized workers. These days, unions win higher wages for employees only at companies with competitive advantages that allow them to pay higher wages, such as successful research and development (R&D) projects or capital investments.

Unions effectively tax these investments by negotiating higher wages for their members, thus lowering profits. Unionized companies respond to this union tax by reducing investment. Less investment makes unionized companies less competitive.

This, along with the fact that unions function as labor cartels that seek to reduce job opportunities, causes unionized companies to lose jobs. Economists consistently find that unions decrease the number of jobs available in the economy. The vast majority of manufacturing jobs lost over the past three decades have been among union members—non-union manufacturing employment has risen. Research also shows that widespread unionization delays recovery from economic downturns.

Some unions win higher wages for their members, though many do not. But with these higher wages, unions bring less investment, fewer jobs, higher prices, and smaller 401(k) plans for everyone else. On balance, labor cartels harm the economy, and enacting policies designed to force workers into unions will only prolong the recession.

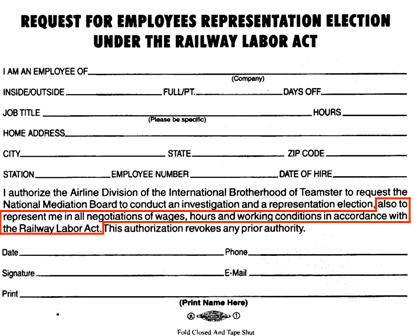

Push for EFCA

Organized labor’s highest legislative priority is the misnamed Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA).[1] This legislation replaces traditional secret-ballot organizing elections with publicly signed cards, allowing union organizers to pressure and harass workers into joining a union. EFCA would also allow the government to impose contracts on newly organized workers and their employers. Both of these changes are highly controversial.

Supporters defend EFCA by sidestepping concerns about taking away workers’ right to vote. They argue that the bill will make it easier for unions to organize workers. They contend that unions are the path to the middle class and that expanding union membership will raise wages and help boost the economy out of the recession.[2] The official case for EFCA rests on the argument that greater union membership benefits the economy.

Opponents of EFCA largely confine their critique to the legislation itself: its undemocratic nature and the problems with giving government bureaucrats the power to dictate work assignments, benefit plans, business operations, and promotion policies. They also argue, however, that increasing union membership will harm the economy.[3]

Economists have exhaustively examined what unions do in the economy. When debating EFCA, Congress should look to the body of academic research to determine whether unions help or hurt the economy.

Unions in Theory

Unions argue that they can raise their members’ wages, but few Americans understand the economic theory explaining how they do this. Unions are labor cartels. Cartels work by restricting the supply of what they produce so that consumers will have to pay higher prices for it. OPEC, the best-known cartel, attempts to raise the price of oil by cutting oil production. As labor cartels, unions attempt to monopolize the labor supplied to a company or an industry in order to force employers to pay higher wages.[4] In this respect, they function like any other cartel and have the same effects on the economy. Cartels benefit their members in the short run and harm the overall economy.

Imagine that General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler jointly agreed to raise the price of the cars they sold by $2,000: Their profits would rise as every American who bought a car paid more. Some Americans would no longer be able to afford a car at the higher price, so the automakers would manufacture and sell fewer vehicles. Then they would need—and hire—fewer workers. The Detroit automakers’ stock prices would rise, but the overall economy would suffer. That is why federal anti-trust laws prohibit cartels and the automakers cannot collude to raise prices.

Now consider how the United Auto Workers (UAW)—the union representing the autoworkers in Detroit—functions. Before the current downturn, the UAW routinely went on strike unless the Detroit automakers paid what they demanded— until recently, $70 an hour in wages and benefits. Gold-plated UAW health benefits for retirees and active workers added $1,200 to the cost of each vehicle that GM produced in 2007.[5] Other benefits, such as full retirement after 30 years of employment and the recently eliminated JOBS bank (which paid workers for not working), added more.

Some of these costs come out of profits, and some get passed to consumers through higher prices. UAW members earn higher wages, but every American who buys a car pays more, stock owners’ wealth falls, and some Americans can no longer afford to buy a new car. The automakers also hire fewer workers because they now make and sell fewer cars.

Unions raise the wages of their members both by forcing consumers to pay more for what they buy or do without and by costing some workers their jobs. They have the same harmful effect on the economy as other cartels, despite benefiting some workers instead of stock owners. That is why the federal anti-trust laws exempt labor unions; otherwise, anti-monopoly statutes would also prohibit union activity.

Unions’ role as monopoly cartels explains their opposition to trade and competition. A cartel can charge higher prices only as long as it remains a monopoly. If consumers can buy elsewhere, a company must cut its prices or go out of business.

This has happened to the UAW. Non-union workers at Honda and Toyota plants now produce high-quality cars at lower prices than are possible in Detroit. As consumers have voted with their feet, the Detroit automakers have been brought to the brink of bankruptcy. The UAW has now agreed to significant concessions that will eliminate a sizeable portion of the gap between UAW and non-union wages. With competition, the union cartel breaks down, and unions cannot force consumers to pay higher prices or capture higher wages for their members.

Unions in Practice

Economic theory consequently suggests that unions raise the wages of their members at the cost of lower profits and fewer jobs, that lower profits cause businesses to invest less, and that unions have a smaller effect in competitive markets (where a union cannot obtain a monopoly). Dozens of economic studies have examined how unions affect the economy, and empirical research largely confirms the results of economic theory.

What follows is a summary of the state of economic research on labor unions. The Appendix summarizes the papers referenced in the main body of this paper.

Unions in the Workplace

Unionizing significantly changes the workplace in addition to its effects on wages or jobs. Employers are prohibited from negotiating directly with unionized employees. Certified unions become employees’ exclusive collective bargaining representatives. All discussions about pay, performance, promotions, or any other working conditions must occur between the union and the employer. An employer may not change working conditions—including raising salaries—without negotiations.

Unionized employers must pay thousands of dollars in attorney’s fees and spend months negotiating before making any changes in the workplace. Unionized companies often avoid making changes because the benefits are not worth the time and cost of negotiations. Both of these effects make unionized businesses less flexible and less competitive.[6]

Final union contracts typically give workers group identities instead of treating them as individuals. Unions do not have the resources to monitor each worker’s performance and tailor the contract accordingly. Even if they could, they would not want to do so. Unions want employees to view the union—not their individual achievements—as the source of their economic gains. As a result, union contracts typically base pay and promotions on seniority or detailed union job classifications. Unions rarely allow employers to base pay on individual performance or promote workers on the basis of individual ability.[7]

Consequently, union contracts compress wages: They suppress the wages of more productive workers and raise the wages of the less competent. Unions redistribute wealth between workers. Everyone gets the same seniority-based raise regardless of how much or little he contributes, and this reduces wage inequality in unionized companies.[8] But this increased equality comes at a cost to employers. Often, the best workers will not work under union contracts that put a cap on their wages, so union firms have difficulty attracting and retaining top employees.[9]

Effect on Wages

Unions organize workers by promising higher wages for all workers. Economists have studied the effects of unions on wages exhaustively and have come to mixed conclusions.

Numerous economic studies compare the average earnings of union and non-union workers, holding other measurable factors—age, gender, education, and industry—constant. These studies typically find that the average union member earns roughly 15 percent more than comparable non-union workers.[10] More recent research shows that errors in the data used to estimate wages caused these estimates to understate the true difference. Estimates that correct these errors show that the average union member earns between 20 percent and 25 percent more than similar non-union workers.[11]

Correlation Is Not Causation

But these studies do not show that unionizing would give the typical worker 20 percent higher wages: Correlation does not imply causation. Controlling for factors like age and education, the average worker in Silicon Valley earns more than the average worker in Memphis, but moving every worker in Memphis to Silicon Valley would not raise his or her wages. Workers in Silicon Valley earn more than elsewhere because they have specialized skills and work for high-paying technology companies, not because they picked the right place to live.

Similarly, it is not necessarily unions that raise wages. They may simply organize workers who would naturally earn higher wages anyway. Unions do not organize random companies. They target large and profitable firms that tend to pay higher wages. Union contracts also make firing underperforming workers difficult, so unionized companies try to avoid hiring workers who might prove to be underperformers. High-earning workers do not want seniority schedules to hold them back and therefore avoid unionized companies.

Estimates from the Same Worker

Economists have attempted to correct this problem by examining how workers’ wages change when they take or leave union jobs. This controls for unobservable worker qualities such as initiative or diligence that raise wages and may be correlated with union membership—the worker has the same skills whether he belongs to a union or not. These studies typically show that workers’ wages rise roughly 10 percent when they take union jobs and fall by a similar amount when they leave those jobs.[12]

Data errors become particularly problematic when following workers over time instead of comparing averages across groups. Some economists argue that these errors artificially diminish the union effect.[13] More recent research explicitly correcting for measurement errors has found that taking union jobs causes workers’ wages to rise between 8 percent and 12 percent.[14] One Canadian study expressly examined how much of the difference between union and non-union wages was caused by unions and how much came from unmeasured individual skills. Over three-fifths of the higher wages earned by union members came from having more valuable skills, not from union membership itself.[15] Just as the land surrounding Silicon Valley does not itself raise wages, most of the difference between union and non-union wages has little or nothing to do with unions themselves.

Wage Changes After Unionization

Studies tracking individual workers also do not prove that unionizing necessarily raises wages. Individual data do not account for firm-specific factors, such as large firms both paying higher wages and being targeted more commonly for organizing drives.

To discover the causal affect of organizing on wages, researchers compare wage changes at newly organized plants with wage changes at plants where organizing drives failed. Such studies look at the same workers and same plants over time, thereby controlling for many unmeasured effects. These studies come to the surprising conclusion that forming a union does not raise workers’ wages.[16] Wages do not rise in plants that unionize relative to plants that vote against unionizing.

Several of the authors of these studies have endorsed EFCA, but their research argues that expanding union membership will not raise wages. This should not come as a complete surprise. Unions in competitive markets have little power to raise wages because companies cannot raise prices without losing customers. Additionally, some unions— such as the Service Employees International Union—have expanded by striking deals promising not to seek wage increases for workers if the employer agrees not to campaign against the union.

Total Wage Effects

While economic research as a whole does not conclusively disprove that unions raise wages, some studies do come to this conclusion. It is difficult to reconcile these studies with the large body of other research showing that union members earn more than non-union members, or with the strong evidence that unions reduce profits.

A better summary of the economic research is that unions do not increase workers’ wages by nearly as much as they claim and that, at a number of companies, they do not raise wages at all. Once researchers control for individual ability, unions raise wages between 0 percent and 10 percent, depending on the circumstances of the particular companies and workers.

Effect on Businesses

Union wage gains do not materialize out of thin air. They come out of business earnings. Other union policies, such as union work rules designed to increase the number of workers needed to do a job and stringent job classifications, also raise costs. Often, unionized companies must raise prices to cover these costs, losing customers in the process. Fewer customers and higher costs would be expected to cut businesses’ earnings, and economists find that unions have exactly this effect. Unionized companies earn lower profits than are earned by non-union businesses.

Studies typically find that unionized companies earn profits between 10 percent and 15 percent lower than those of comparable non-union firms.[17] Unlike the findings with respect to wage effects, the research shows unambiguously that unions directly cause lower profits. Profits drop at companies whose unions win certification elections but remain at normal levels for non-union firms. One recent study found that shareholder returns fall by 10 percent over two years at companies where unions win certification.[18]

These studies do not create controversy, because both unions and businesses agree that unions cut profits. They merely disagree over whether this represents a feature or a problem. Unions argue that they get workers their fair share, while employers complain that union contracts make them uncompetitive.

Which Profits Fall?

Unions do not have the same effect at all companies. In competitive markets, unions have very little power to raise wages and reduce profits. Companies cannot raise prices without losing business, but if union wage increases come out of normal operating profits, investors take their money elsewhere. However, not all markets are perfectly competitive. Unions can redistribute from profits to wages when firms have competitive advantages.

Economic research shows that union wage gains come from redistributing abnormal profits that firms earn from competitive advantages such as limited foreign competition or from growing demand for the company’s products. Unions also redistribute the profits that stem from investments in successful R&D projects and long-lasting capital investments.[19]

Consider a manufacturing company that invests in productivity-enhancing machines. Workers’ output increases, and the company earns higher profits years after the initial investment. It has an advantage in the marketplace over companies that did not make that same investment. Unions redistribute the higher profits from this investment—not the normal return from operating a business—to their members.

Unions Reduce Investment

In essence, unions tax investments that corporations make, redistributing part of the return from these investments to their members. This makes undertaking a new investment less worthwhile. Companies respond to the union tax in the same way they respond to government taxes on investment—by investing less. By cutting profits, unions also reduce the money that firms have available for new investments, so they also indirectly reduce investment.

Consider General Motors, now on the verge of bankruptcy. The UAW agreed to concessions in the 2007 contracts and has made more concessions since then. If General Motors had invested successfully in producing an inexpensive electric car, and if sales of that new vehicle had made GM profitable, then the UAW would not have agreed to any concessions. The UAW would be demanding higher wages. After the union tax, R&D investments earn lower returns for GM than for its non-union competitors such as Toyota and Honda.

Economic research demonstrates overwhelmingly that unionized firms invest less in both physical capital and intangible R&D than non-union firms do.[20] One study found that unions directly reduce capital investment by 6 percent and indirectly reduce capital investment through lower profits by another 7 percent. This same study also found that unions reduce R&D activity by 15 percent to 20 percent.[21] Other studies find that unions reduce R&D spending by even larger amounts.[22]

Research shows that unions directly cause firms to reduce their investments. In fact, investment drops sharply after unions organize a company. One study found that unionizing reduces capital investment by 30 percent—the same effect as a 33 percentage point increase in the corporate tax rate.[23]

Unions Reduce Jobs

Lower investment obviously hinders the competitiveness of unionized firms. The Detroit automakers have done so poorly in the recent economic downturn in part because they invested far less than their non-union competitors in researching and developing fuel-efficient vehicles. When the price of gas jumped to $4 a gallon, consumers shifted away from SUVs to hybrids, leaving the Detroit carmakers unable to compete and costing many UAW members their jobs.

Economists would expect reduced investment, coupled with the intentional effort of the union cartel to reduce employment, to cause unions to reduce jobs in the companies they organize. Economic research shows exactly this: Over the long term, unionized jobs disappear.

Consider the manufacturing industry. Most Americans take it as fact that manufacturing jobs have decreased over the past 30 years. However, that is not fully accurate. Chart 1 shows manufacturing employment for union and non-union workers. Unionized manufacturing jobs fell by 75 percent between 1977 and 2008. Non-union manufacturing employment increased by 6 percent over that time. In the aggregate, only unionized manufacturing jobs have disappeared from the economy. As a result, collective bargaining coverage fell from 38 percent of manufacturing workers to 12 percent over those years.

Manufacturing jobs have fallen in both sectors since 2000, but non-union workers have fared much better: 38 percent of unionized manufacturing jobs have disappeared since 2000, compared to 18 percent of non-union jobs.[24]

Other industries experienced similar shifts. Chart 2 shows union and non-union employment in the construction industry. Unlike the manufacturing sector, the construction industry has grown considerably since the late 1970s. However, in the aggregate, that growth has occurred exclusively in non-union jobs, expanding 159 percent since 1977. Unionized construction jobs fell by 17 percent. As a result, union coverage fell from 38 percent to 16 percent of all construction workers between 1977 and 2008.[25]

This pattern holds across many industries: Between new companies starting up and existing companies expanding, non-union jobs grow by roughly 3 percent each year, while 3 percent of union jobs disappear.[26] In the long term, unionized jobs disappear and unions need to replenish their membership by organizing new firms. Union jobs have disappeared especially quickly in industries where unions win the highest relative wages.[27] Widespread unionization reduces employment opportunities.

More Contractions but Not More Bankruptcies

Counterintuitively, research shows that unions do not make companies more likely to go bankrupt. Unionized firms do not go out of business at higher rates than non-union firms.[28] Unionized firms do, however, shed jobs more frequently and expand less frequently than non-union firms.[29] Most studies show that jobs contract or grow more slowly, by between 3 and 4 percentage points a year, in unionized businesses than they do in non-unionized businesses.[30]

How can union firms both lose jobs at faster rates than non-union firms and have no greater likelihood of going out of business? Unions try not to ruin the companies they organize. They agree to concessions at distressed firms to keep them afloat. However, unions prefer layoffs over pay cuts when a firm does not face imminent liquidation. Layoffs at most union firms occur on the basis of seniority: Newer hires lose their jobs before workers with more tenure lose theirs. Senior members with the greatest influence in the union know that they will keep their jobs in the event of layoffs but that they will also suffer pay reductions. Consequently, unions negotiate contracts that allow firms to lay off newer hires and keep pay high for senior members instead of contracts that lower wages for all workers and preserve jobs.[31]

Economists expect unions to behave like this. They are cartels that work by keeping employment down to raise wages for their members.

Consider General Motors. GM shed tens of thousands of jobs over the past decade, but the UAW steadfastly refused to any concessions that would have improved GM’s competitive standing. Only in 2007—with the company on the brink of bankruptcy—did the UAW agree to lower wages, and then only for new hires. The UAW accepted steep job losses as the price of keeping wages high for senior members. If GM does file for bankruptcy, it will likely emerge as a smaller but more competitive firm. It will still exist and employ union members—but tens of thousands of UAW members have lost their jobs.

Unions Cause Job Losses

The balance of economic research shows that unions do not just happen to organize firms with more layoffs and less job growth: They cause job losses. Most studies find that jobs drop at newly organized companies, with employment falling between 5 percent and 10 percent.[32]

One prominent study comparing workers who voted narrowly for unionizing with those who voted narrowly against unionizing came to the opposite conclusion, finding that newly organized companies were no more likely to shed jobs or go out of business.[33] That study, however—prominently cited by labor advocates—essentially found that unions have no effect on the workplace. Jobs did not disappear, but wages did not rise either. Unless the labor movement wants to concede that unions do not raise wages, it cannot use this research to argue that unions do not cost jobs.

Slower Economic Recovery

Labor cartels attempt to reduce the number of jobs in an industry in order to raise the wages of their members. Unions cut into corporate profitability, also reducing business investment and employment over the long term.

These effects do not help the job market during normal economic circumstances, and they cause particular harm during recessions. Economists have found that unions delay economic recoveries. States with more union members took considerably longer than those with fewer union members to recover from the 1982 and 1991 recessions.[34]

Policies designed to expand union membership whether workers want it or not—such as the misnamed Employee Free Choice Act—will delay the recovery. Economic research has demonstrated that policies adopted to encourage union membership in the 1930s deepened and prolonged the Great Depression. President Franklin Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act. He also permitted industries to collude to reduce output and raise prices—but only if the companies in that industry unionized and paid above-market wages.

This policy of cartelizing both labor and businesses caused over half of the economic losses that occurred in the 1930s.[35] Encouraging labor cartels will also lengthen the current recession.

Conclusion

Unions simply do not provide the economic benefits that their supporters claim they provide. They are labor cartels, intentionally reducing the number of jobs to drive up wages for their members.

In competitive markets, unions cannot cartelize labor and raise wages. Companies with higher labor costs go out of business. Consequently, unions do not raise wages in many newly organized companies. Unions can raise wages only at companies that have competitive advantages that permit them to pay higher wages, such as successful R&D projects or long-lasting capital investments.

On balance, unionizing raises wages between 0 percent and 10 percent, but these wage increases come at a steep economic cost. They cut into profits and reduce the returns on investments. Businesses respond predictably by investing significantly less in capital and R&D projects. Unions have the same effect on business investment as does a 33 percentage point corporate income tax increase.

Less investment makes unionized companies less competitive, and they gradually shrink. Combined with the intentional efforts of a labor cartel to restrict labor, unions cut jobs. Unionized firms are no more likely than non-union firms to go out of business—unions make concessions to avoid bankruptcy—but jobs grow at a 4 percent slower rate at unionized businesses than at other companies. Over time, unions destroy jobs in the companies they organize. In manufacturing, three-quarters of all union jobs have disappeared over the past three decades, while the number of non-union jobs has increased.

No economic theory posits that cartels improve economic efficiency. Nor has reality ever shown them to do so. Union cartels retard economic growth and delay recovery from recession. Congress should remember this when considering legislation, such as EFCA, that would abolish secret-ballot elections and force workers to join unions.

James Sherk is Bradley Fellow in Labor Policy in the Center for Data Analysis at The Heritage Foundation.

Appendix

Summaries of Studies Used in This Paper and Their Key Findings

Abowd, John, and Henry Farber, Job Queues and the Union Status of Workers, Industrial and Labor Relations Review , Vol. 35, No. 3 (April 1982), pp. 354-367.

Uses Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) data to examine why workers do or do not join unions. Finds that both workers’ and firms’ choice matters. Employers want to hire high-skill workers, but few high-skill workers apply for union jobs. Low-skill workers want to work for unionized companies, but employers do not want to hire them. As a result, most union members come from the middle of the skill distribution—workers who want to work for a unionized company and whom employers want to hire.

Betts, Julian, Cameron W. Odgers, and Michael K. Wilson, The Effects of Unions on Research and Development: An Empirical Analysis Using Multi-Year Data, Canadian Journal of Economics. Vol. 34, No. 3 (August 2001), pp. 785-806.

Examines the relationship between unionization and R&D, using industry-level data from Canada. Finds that R&D falls by 28 percent to 50 percent for an industry that moves from 0 percent to 42 percent unionization rates.

Blanchflower, David G. Neil Millward, and Andrew J. Oswald, Unionization and Employment Behavior, Economic Journal. Vol. 101, No. 407 (July 1991), pp. 815-834.

Examines the effects of unions on employment growth in the United Kingdom, using data from a sample of individual firms in both the manufacturing and service sectors. Finds that jobs contract 3 percentage points more quickly in unionized companies than in comparable non-union firms.

Bratsberg, Bernt, and James F. Ragan, Jr. Changes in the Union Wage Premium by Industry, Industrial and Labor Relations Review , Vol. 56, No. 1 (October 2002), pp. 65-83.

Uses Current Population Survey (CPS) data from 1972 to 1999 to examine changes in union wages and employment in 32 industries. Finds no significant trend in the union wage gap in the aggregate over this time but significant changes at the industry level. Industries with large union wage gaps saw them fall, while the union wage premium rose for industries that started with low premiums. Also finds that the industries with higher premiums had larger decreases in union jobs.

Bronars, Stephen G. and Donald R. Deere, Unionization, Incomplete Contracting, and Capital Investment, Journal of Business , Vol. 66, No. 1 (January 1993), pp. 117-132.

Presents both theory and empirical evidence on the effect of unions on investment. Theoretically, once a company makes an investment, the union has the power to tax it by demanding higher wages paid for by the returns to that investment. Companies respond by investing less, and unionized companies become less competitive and lose jobs in the long run. Even if unions would prefer that companies invest more to stay viable, they cannot credibly commit to not seeking higher wages once the firm makes the investment. Empirical data on publicly traded firms between 1970 and 1976 support the theory. A 35 percent increase in a firm’s unionization rate is associated with investing 8 percent less in physical capital, 51 percent less in R&D, and 36 percent less in advertising. Employment growth falls by 35 percent. Implies that decreasing union membership in the economy results from unionized firms becoming less competitive.

Bronars, Stephen, Donald R. Deere, and Joseph Tracy, The Effects of Unions on Firm Behavior: An Empirical Analysis Using Firm-Level Data, Industrial Relations. Vol. 33, No. 4 (October 1994), pp. 426-451.

Uses firm-level data to compare differences in behavior and performances between union and non-union firms between 1971 and 1982. Finds that a 50 percent increase in the ratio of union employees to total employees at a firm decreases R&D spending by 18 percent to 25 percent, decreases annual sales growth by 1 percent to 4 percent, decreases annual employment growth by 3 percent to 6 percent, and decreases profits by 8 percent to 20 percent. Also finds that unionization decreases productivity in non-manufacturing firms and increases productivity in manufacturing firms.

Budd, John W. and In-Gang Na, The Union membership Wage Premium for Employees Covered by Collective Bargaining Agreements, Journal of Labor Economics , Vol. 18, No. 4 (October 2000), pp. 783-807.

Uses CPS data to examine the difference in wages between full-time private-sector union members and non-union workers between 1983 and 1993. Finds that union members earn between 12 percent and 14 percent more than non-union members after controlling for other observable factors such as experience and education.

Card, David, The Effect of Unions on the Structure of Wages: A Longitudinal Analysis, Econometrica. Vol. 64, No. 4 (July 1996), pp. 957-979.

Uses CPS data from 1987-1988 to examine the differences between estimates of the average earnings of union and non-union workers and the wage gains to individual workers who join and leave union jobs. Accounts for errors in CPS estimates of whether workers belong to a union. Finds that these errors explain the difference and that workers’ wages rise approximately 17 percent when they join a union, with larger increases for low-skill workers. Also finds that high-skill workers are less likely to apply for union jobs and that unionized employers are less likely to hire low-skill workers.

Card, David, Thomas Lemieux, and W. Craig Riddell, Unions and the Wage Structure, in International Handbook of Trade Unions (Cheltenham, U.K. Edward Elgar, 2003).

Finds that unions reduce inequality for men but not for women in the United States, Canada, and Great Britain.

Cavanaugh, Joseph, Asset-Specific Investment and Unionized Labor, Industrial Relations. Vol. 37, No. 1 (January 1998), pp. 35-50.

Presents both theory and empirical evidence on the effect of unions on investment. Theoretically, once a company makes an investment, the union has the power to tax it by demanding higher wages paid for by the returns to that investment. Companies respond by investing less, and unionized companies become less competitive and lose jobs in the long run. Even if unions would prefer that companies invest more to stay viable, they cannot credibly commit to not seeking higher wages once the firm makes the investment. Empirical data on manufacturing firms between 1973 and 1982 support the theory. Unions reduce sales, market value, investment, and employment, with the largest effects occurring among firms that have made the largest investments in the past.

Checchi, Daniele, Jelle Visser, and Herman G. Van de Werfhorst, Inequality and Union membership: The Impact of Relative Earnings Position and Inequality Attitudes, IZA Discussion Paper No. 2691, March 2007.

Examines the connection between union membership and economic inequality. Finds that union members come from the middle of the wage distribution, with both high- and low-income workers less likely to join a union. Also investigates how attitudes toward inequality affect the decision to join a union. Workers who believe that economic inequality is a serious problem are significantly more likely to join unions than are those who do not.

Cole, Harold L. and Lee E. Ohanian, New Deal Policies and the Persistence of the Great Depression: A General Equilibrium Analysis, Journal of Political Economy. Vol. 112, No. 4 (August 2004), pp. 779-816.

Examines the cause of the depth and persistence of the Great Depression. President Roosevelt permitted companies to form cartels that raised prices for consumers so long as those companies unionized and paid higher wages. This policy successfully kept wages high for workers with jobs during the Depression. However, it prolonged and extended the Depression and accounts for more than half of the loss in economic output in the 1930s. The resumption of anti-trust enforcement mechanisms and measures that weaken union power in the 1940s explains the post-war recovery.

Connolly, Robert, Barry T. Hirsch, and Mark Hirschey, Union Rent Seeking, Intangible Capital, and Market Value of the Firm, Review of Economics and Statistics. Vol. 68, No. 4 (November 1986), pp. 567-577.

Examines the effects of unions on investment by comparing union and non-union firms. However, Connolly et al. use industry-level measures of union density instead of firm-level data. Finds that unionized firms earn a lower return on R&D investments and respond by reducing R&D spending. Firms that move from having 20 percent of their workers belonging to unions to 50 percent decrease R&D spending by 40 percent relative to average R&D spending levels.

DiNardo, John, and David S. Lee, Economic Impacts of New Unionization on Private Sector Employers: 1984-2001, The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Vol. 119, No. 4 (November 2004), pp. 1383-1441.

Compares companies whose workers voted narrowly for a union with companies whose workers voted narrowly against a union. Since the difference between winning and losing is close to random, this provides an estimate of the causal effect of randomly organizing a given company. Finds that workers who vote to join a union do win certification but that unions have essentially no effect on the firm or the workers. Wages do not rise, and employment and productivity do not fall. Unionized companies are no more likely to go out of business than are non-union firms.

Dunne, Timothy, and David MacPherson, Unionism and Gross Employment Flows, Southern Economic Journal , Vol. 60, No. 3 (January 1994), pp. 727-738.

Uses industry-level census data from 1977 to 1982 to examine the effect of unions on employment. Finds that plants in more heavily unionized manufacturing sectors are no more likely to go out of business than are plants in less heavily unionized sectors. However, plants in more heavily unionized sectors are more likely to lose jobs and grow at slower rates than plants in less heavily unionized sectors are.

Fallick, Bruce, and Kevin Hassett, Investment and Union Certification, Journal of Labor Economics , Vol. 17, No. 3 (July 1999), pp. 570-582.

Examines the effects of union certification on firm performance. Finds that winning union recognition reduces investment the year following certification by 30 percent—the same effect as increasing the corporate income tax rate by 33 percentage points.

Farber, Henry, and Bruce Western, Accounting for the Decline of Unions in the Private Sector, 1973-1998, Journal of Labor Research. Vol. 22, No. 2 (September 2001), pp. 459-485.

Examines the cause of decreased union membership between 1973 and 1998. Finds that relatively little of the decline can be explained by any change in organizing success rates. Instead, most of the decline occurred because the union sector grows faster than the non-union sector. The number of jobs in unionized companies shrank by an average of 3 percent a year during that time, and the number of jobs in non-union companies grew by 3 percent a year. Unions do not organize enough new members to replace the union jobs lost annually, so union membership gradually declines.

Freeman, Richard B. Union Wage Practices and Wage Dispersion Within Establishments, Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Vol. 36, No. 1 (October 1982), pp. 3-21.

Examines how unions change pay policies within firms. Finds that unions typically negotiate pay on the basis of job classifications or seniority-based promotions and resist pay on the basis of individual merit or ability. Consequently, unions compress wages within firms, raising wages for less productive workers but lowering them for more productive workers.

Freeman, Richard B. and Morris M. Kleiner, The Impact of New Unionization on Wages and Working Conditions, Journal of Labor Economics. Vol. 8, No. 1 (January 1990), pp. S8-25.

Uses a survey of firms that underwent organizing drives and their closest competitors to estimate the effects of unionization on businesses. Finds only a 3 percent to 4 percent increase in average wages if the union wins. Also finds that unions reduce employment between 3 percent and 6 percent at companies that organize relative to those in which workers vote down the union. Also finds that the presence of a written grievance procedure makes it less likely that unions will win the election.

Freeman, Richard B. and Morris M. Kleiner, Do Unions Make Enterprises Insolvent? Industrial and Labor Relations Review , Vol. 52, No. 4 (July 1999), pp. 510-527.

Uses both firm-level and individual-level data to examine whether unionized companies go out of business at higher rates than do non-union companies. Examines a sample of publicly traded firms between 1983 and 1990 and finds that union firms do not file for bankruptcy at higher rates. Examines CPS data on displaced workers from the mid-1990s and finds that union members are no more likely than other workers to report losing their job because their company went out of business.

Hirsch, Barry T. Union Coverage and Profitability Among U.S. Firms, The Review of Economics and Statistics , Vol. 73, No. 1 (February 1991), pp. 69-77.

Examines how unions affect the behavior and performance of manufacturing firms, using firm-level data from 1968 to 1980. Finds that unionized companies have lower profits than non-union firms, with unionized firm values approximately 20 percent lower than comparable non-union firms. Union gains come out of profits earned by companies in growing industries or with limited foreign competition and from the returns to physical capital and R&D. Unions thus reduce both the money that firms have to invest and the returns on investment. Both of these effects cause unionized firms to cut investment in physical capital by 13 percent and investment in R&D by 15 percent to 20 percent.

Hirsch, Barry T. Firm Investment Behavior and Collective Bargaining Strategy, Industrial Relations , Vol. 31, No. 1 (Winter 1992), pp. 95-121.

Examines differences in investment spending in a sample of union and non-union companies between 1972 and 1980. Finds that unions tax the returns to business investments by demanding higher wages, paid for by the returns to those investments. Consequently, unionized companies spend 20 percent less on physical capital and 30 percent less on R&D. Reduced investment harms unionized companies in the long term, and jobs gradually shift to non-union firms that invest more.

Hirsch, Barry T. Reconsidering Union Wage Effects: Surveying New Evidence on an Old Topic, Journal of Labor Research , Vol. 25, No. 2 (April 2004), pp. 233-266.

Uses CPS data to examine the difference in average wages between union and non-union workers, controlling for observable characteristics. Finds that union members earn 14 percent more. However, removing workers with imputed earnings—workers who did not answer the survey and who were assigned the earnings of another worker—from the sample raises the estimated union premium to 20 percent. Assuming that 2 percent of reported union members actually do not belong to a union, as one study suggests, raises the union premium to 28 percent. Concludes that economists should raise the consensus estimate of a 15 percent union wage premium.

Hirsch, Barry T. Sluggish Institutions in a Dynamic World: Can Unions and Industrial Competition Coexist? Journal of Economic Perspectives , Vol. 22, No. 1 (Winter 2008), pp. 153-176.

Finds that the high cost of negotiating changes in working conditions causes a slow response to economic changes in union companies and that unions tax profitable investments by demanding higher wages when they occur, discouraging investment. Both factors disadvantage union firms in the marketplace and cause jobs to shift to non-union companies. Uses a case study of the airline and automotive industries to illustrate these effects.

Hirsch, Barry T. and Edward J. Schumacher, Unions, Wages, and Skills, Journal of Human Resources , Vol. 33, No. 1 (Winter 1998), pp. 201-219.

Extends the research of Card, The Effect of Unions on the Structure of Wages: A Longitudinal Analysis. Uses CPS data from 1989 to 1995 and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) to examine wage changes for workers who join and leave unions, explicitly correcting for measurement error. Finds that unions raise the wages of job changers by 8 percent to 12 percent, roughly a third below the estimates comparing average wages between union and non-union workers. Also finds that unions have the same effect on wages across the skill distribution and that unionized companies employ workers of average ability: Low-skill workers are not hired, and high-skill workers do not apply for union jobs.

Jakubson, George, Estimation and Testing of the Union Wage Effect Using Panel Data, Review of Economic Studies , Vol. 58, No. 5 (October 1991), pp. 971-991.

Estimates the effects of unions on wages while controlling for unmeasured effects that may be correlated with both higher wages and union membership. UsesPSID data to examine the wages of workers who join or leave unionized firms. Finds that wages rise roughly 8 percent for workers who start union jobs, well below the 20 percent difference in average wages between union and non-union workers. Implies that a large portion of the gap between union and non-union wages is explained by factors other than the causal effect of unions on wages.

Kang, Changhui, Union Wage Effect: New Evidence from Matched Employer-Employee Data, National University of Singapore, Department of Economics, Departmental Working Paper No. 0302, 2003.

Uses NLSY data to estimate wage changes for workers who join and leave unions. Estimates that workers who join unions see an 8 percent wage increase, half the size of the 15 percent difference in wages between union and non-union workers. Unobserved skill differences between union and non-union workers explain a significant portion of the apparent union wage premium.

Krol, Robert, and Shirley Svorny, Unions and Employment Growth: Evidence from State Economic Recoveries, Journal of Labor Research. Vol. 28, No. 3 (Summer 2007), pp. 525-535.

Examines state economic recoveries from the 1982 and 1991 recessions. Finds that the unemployment rate took considerably longer to fall after the recessions ended in states with higher union densities than it did in states with fewer union members.

Lalonde, Robert J. Gerard Marschke, and Kenneth Troske, Using Longitudinal Data on Establishments to Analyze the Effects of Union Organizing Campaigns in the United States, Annales d’Economie et de Statistique. Vol. 41-42 (January-June 1996), pp. 155-185.

Examines changes in manufacturing companies before and after successful union organizing drives. Finds that employment among production employees drops by 11 percent two years after the election and that wages do not rise. Also finds that productivity falls.

Lee, David, and Alexandre Mas, Long-Run Impacts of Unions on Firms: New Evidence from Financial Markets, 1961-1999, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 14709, February 2009.

Compares changes in the market value of firms whose workers vote to unionize to comparable non-union firms and finds that unionizing reduces the cumulative return to investors by 10 percent over two years. Also compares the effects on stock prices of firms whose workers vote narrowly to unionize and firms whose workers vote narrowly against unionizing and finds no significant difference. Reconciles these findings by showing that firms with workers more likely to be undecided on unionizing pay higher wages—hence the lack of a difference when comparing firms that narrowly vote yes with those that narrowly vote no. Calculates that passing card-check legislation would reduce the average market value of all firms by 4.3 percent.

Lemieux, Thomas, Estimating the Effects of Unions on Wage Inequality in a Panel Data Model with Comparative Advantage and Nonrandom Selection, Journal of Labor Economics , Vol. 16, No. 2 (April 1998), pp. 261-291.

Estimates the effects of unions on wages in Canada, explicitly correcting for measurement errors. Finds that the average union member earns 28 percent more than the average non-union member. However, unions cause less than two-fifths of this wage premium. The rest comes from unmeasured individual characteristics. Workers who switch to union jobs see their wages rise by only 10 percent.

Leonard, Jonathan S. Unions and Employment Growth, Industrial Relations. Vol. 31, No. 1 (Winter 1992), pp. 80-94.

Examines the effects of unionism on employment growth in a sample of California manufacturing plants. Finds that jobs shrink by 4 percentage points more rapidly a year in unionized plants than in comparable non-union plants. The slower growth and faster contractions of unionized businesses explain up to three-fifths of the decline in union membership.

Lewis, H. Gregg, Union Relative Wage Effects: A Survey (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986).

Extensive survey of the effects of unions on wages. Among other findings, estimates that the average union member earns 15 percent more than the average non-union member after controlling for observable characteristics such as education and industry.

Linneman, Peter D. Michael L. Wachter, and William H. Carter, Evaluating the Evidence on Union Employment and Wages, Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Vol. 44, No. 1 (October 1990), pp. 34-53.

Uses CPS data from 1973 to 1986 to examine changes in the union wage premium and union employment. Shows that the industries with the largest increase in union wages are those in which union membership has declined the most. Also shows that non-union employment in those sectors has held steady. What appears to be de-industrialization is actually de-unionization, with unionized manufacturing jobs disappearing and non-union employment stable.

Long, Richard J. The Effect of Unionization on Employment Growth of Canadian Companies, Industrial and Labor Relations Review , Vol. 46, No. 4 (July 1993), pp. 691-703.

Examines changes in employment in a sample of Canadian firms between 1980 and 1985. Finds that jobs grow 4 percentage points a year more slowly in unionized manufacturing and non-manufacturing firms than in comparable non-union firms.

Medoff, James L. Layoffs and Alternatives Under Trade Unions in U.S. Manufacturing, The American Economic Review , Vol. 69, No. 3 (June 1979), pp. 380-395.

Examines how unionized and non-unionized workplaces respond to changing demand for labor. When business slows, unionized firms are more likely to lay off workers and less likely to cut wages or reduce hours than comparable nonunion firms are. This occurs because union seniority systems protect senior members from layoffs so that only the newest hires lose their jobs. Consequently, most union members prefer layoffs of the junior union members to cuts in their wages or hours.

Metcalf, David, Kirstine Hansen, and Andy Charlwood, Unions and the Sword of Justice: Unions and Pay Systems, Pay Inequality, Pay Discrimination and Low Pay, National Institute Economic Review. Vol. 176, No. 1 (April 2001), pp. 61-75.

Examines why wages vary less between workers in union firms than they do between workers in non-union firms in the United Kingdom. Finds that union members are more similar than workers in non-union firms and naturally earn more similar wages. Also finds that unions negotiate contracts that reduce the returns to individual skills and ability, such as seniority pay instead of merit pay. As a result, unions compress pay, raising wages for less capable workers and lowering them for more productive workers.

Wachter, Michael, Theories of the Employment Relationship: Choosing Between Norms and Contracts, in Theoretical Perspectives on Work and the Employment Relationship . ed. Bruce E. Kaufman (Champaign, Ill. Industrial Relations Research Association, 2004), pp. 163-193.

Examines advantages and disadvantages of using union and non-union approaches to guide firm policies. Finds that both systems can be advantageous under certain circumstances but that larger transaction costs exist in unionized companies because of the time and cost of negotiating changes in the work environment. Collective bargaining faces a significant disadvantage in the marketplace as long as workers feel sufficiently protected from arbitrary management in non-union firms.

[3] Dr. Anne Layne-Farrar, An Empirical Assessment of the Employee Free Choice Act: The Economic Implications,papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm

[4] George Borjas, Labor Economics. 3rd edition (Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill, 2005).

[5] James Sherk, Auto Bailout Ignores Excessive Labor Costs,www.heritage.org/Research/Economy/wm2135.cfm .

[6] Michael L. Wachter, Theories of the Employment Relationship: Choosing Between Norms and Theoretical Perspectives on Work and the Employment Relationship. ed. Bruce E. Kaufman (Champaign, Ill. Industrial Relations Research Association, 2004), pp. 163-193; Barry T. Hirsch, Sluggish Institutions in a Dynamic World: Can Unions and Industrial Competition Coexist? Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 22, No. 1 (Winter 2008), pp. 153-176.

[7] David Metcalf, Kirstine Hansen, and Andy Charlwood, Unions and the Sword of Justice: Unions and Pay Systems, Pay Inequality, Pay Discrimination and Low Pay, National Institute Economic Review. Vol. 176, No. 1 (April 2001), pp. 61-75; Richard B. Freeman, Union Wage Practices and Wage Dispersion Within Establishments, Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Vol. 36, No. 1 (October 1982), pp. 3-21.

[8] Freeman, Union Wage Practices and Wage Dispersion Within Establishments; David Card, Thomas Lemieux, and W. Craig Riddell, Unions and the Wage Structure, in International Handbook of Trade Unions (Cheltenham, U.K. Edward Elgar, 2003).

[9] David Card, The Effect of Unions on the Structure of Wages: A Longitudinal Analysis, Econometrica. Vol. 64, No. 4 (July 1996), pp. 957-979; Daniele Checchi, Jelle Visser, and Herman G. Van de Werfhorst, Inequality and Union Membership: The Impact of Relative Earnings Position and Inequality Attitudes, IZA Discussion Paper No. 2691, March 2007; John Abowd and Henry Farber, Job Queues and the Union Status of Workers, Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Vol. 35, No. 3 (April 1982), pp. 354-367.

[10] John W. Budd and In-Gang Na, The Union Membership Wage Premium for Employees Covered by Collective Bargaining Agreements, Journal of Labor Economics. Vol. 18, No. 4 (October 2000), pp. 783-807; H. Gregg Lewis, Union Relative Wage Effects: A Survey (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986).

[11] Barry T. Hirsch, Reconsidering Union Wage Effects: Surveying New Evidence on an Old Topic, Journal of Labor Research. Vol. 25, No. 2 (April 2004), pp. 233-266.

[12] George Jakubson, Estimation and Testing of the Union Wage Effect Using Panel Data, Review of Economic Studies. Vol. 58, No. 5 (October 1991), pp. 971-991.

[13] Card, The Effect of Unions on the Structure of Wages: A Longitudinal Analysis.

[14] Barry T. Hirsch and Edward J. Schumacher, Unions, Wages, and Skills, Journal of Human Resources. Vol. 33, No. 1 (Winter 1998), pp. 201-219; Changhui Kang, Union Wage Effect: New Evidence from Matched Employer-Employee Data, National University of Singapore, Department of Economics, Departmental Working Paper No. wp0302, 2003.

[15] Thomas Lemieux, Estimating the Effects of Unions on Wage Inequality in a Panel Data Model with Comparative Advantage and Nonrandom Selection, Journal of Labor Economics. Vol. 16, No. 2 (April 1998), pp. 261-291.

[16] Robert J. Lalonde, Gerard Marschke, and Kenneth Troske, Using Longitudinal Data on Establishments to Analyze the Effects of Union Organizing Campaigns in the United States, Annales d’ Economie et de Statistique. Vol. 41-42 (January- June 1996), pp. 155-185; Richard B. Freeman and Morris M. Kleiner, The Impact of New Unionization on Wages and Working Conditions, Journal of Labor Economics. Vol. 8, No. 1 (January 1990), pp. S8-25; John DiNardo and David S. Lee, Economic Impacts of New Unionization on Private Sector Employers: 1984-2001, The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Vol. 119, No. 4 (November 2004), pp. 1383-1441.

[17] Barry T. Hirsch, Union Coverage and Profitability Among U.S. Firms, The Review of Economics and Statistics. Vol. 73, No. 1 (February 1991), pp. 69-77; Stephen G. Bronars, Donald R. Deere, and Joseph S. Tracy, The Effects of Unions on Firm Behavior: An Empirical Analysis Using Firm-Level Data, Industrial Relations. Vol. 33, No. 4 (October 1994) pp. 426-451.

[18] David Lee and Alexandre Mas, Long-Run Impacts of Unions on Firms: New Evidence from Financial Markets, 1961-1999, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 14709, February 2009.

[19] Barry T. Hirsch, Labor Unions and the Economic Performance of U.S. Firms (Kalamazoo, Mich. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1991); Joseph Cavanaugh, Asset-Specific Investment and Unionized Labor, Industrial Relations. Vol. 37, No. 1 (January 1998), pp. 35-50.

[20] Robert Connolly, Barry T. Hirsch, and Mark Hirschey, Union Rent Seeking, Intangible Capital, and Market Value of the Firm, Review of Economics and Statistics. Vol. 68, No. 4 (November 1986), pp. 567-577; Bronars, Deere, and Tracy, The Effects of Unions on Firm Behavior; Stephen G. Bronars and Donald R. Deere, Unionization, Incomplete Contracting, and Capital Investment, Journal of Business. Vol. 66, No. 1 (January 1993), pp. 117-132; Barry T. Hirsch, Firm Investment Behavior and Collective Bargaining Strategy, Industrial Relations. Vol. 31, No. 1 (Winter 1992), pp. 95-121.

[21] Hirsch, Labor Unions and the Economic Performance of U.S. Firms .

[22] Julian Betts, Cameron W. Odgers, and Michael K. Wilson, The Effects of Unions on Research and Development: An Empirical Analysis Using Multi-Year Data, Canadian Journal of Economics. Vol. 34, No. 3 (August 2001), pp. 785-806.

[24] Barry T. Hirsch and David A. Macpherson, Union Membership and Coverage Database from the Current Population Survey,www.unionstats.com/ (May 5, 2009). Union refers to union members and non-union members covered by collective bargaining agreements. Non-union refers to workers not covered by collective bargaining agreements.

[26] Henry Farber and Bruce Western, Accounting for the Decline of Unions in the Private Sector, 1973-1998, Journal of Labor Research . Vol. 22, No. 2 (September 2001), pp. 459-485.

[27] Bernt Bratsberg and James F. Ragan, Jr. Changes in the Union Wage Premium by Industry, Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Vol. 56, No. 1 (October 2002), pp. 65-83; Peter D. Linneman, Michael L. Wachter, and William H. Carter, Evaluating the Evidence on Union Employment and Wages, Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Vol. 44, No. 1 (October 1990), pp. 34-53.

[28] Timothy Dunne and David MacPherson, Unionism and Gross Employment Flows, Southern Economic Journal. Vol. 60, No. 3 (January 1994), pp. 727-738; Richard B. Freeman and Morris M. Kleiner, Do Unions Make Enterprises Insolvent? Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Vol. 52, No. 4 (July 1999), pp. 510-527.

[29] Dunne and MacPherson, Unionism and Gross Employment Flows.

[30] David G. Blanchflower, Neil Millward, and Andrew J. Oswald, Unionization and Employment Behavior, Economic Journal. Vol. 101, No. 407 (July 1991), pp. 815-834; Jonathan S. Leonard, Unions and Employment Growth, Industrial Relations. Vol. 31, No. 1 (Winter 1992), pp. 80-94; Richard J. Long, The Effect of Unionization on Employment Growth of Canadian Companies, Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Vol. 46, No. 4 (July 1993), pp. 691-703.

[31] James L. Medoff, Layoffs and Alternatives Under Trade Unions in U.S. Manufacturing The American Economic Review. Vol. 69, No. 3 (June 1979), pp. 380-395.

[32] Freeman and Kleiner, The Impact of New Unionization on Wages and Working Conditions; Lalonde, Marschke, and Troske, Using Longitudinal Data on Establishments to Analyze the Effects of Union Organizing Campaigns in the United States.

[33] DiNardo and Lee, Economic Impacts of New Unionization on Private Sector Employers: 1984-2001.