Globalization and Its Implications

Post on: 5 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Margaret Stimmann Branson, Associate Director

Center for Civic Education

A paper delivered to the

Democracy and the Globalization of Politics and the Economy

International Conference

Haus auf der Alb, Bad Urach, Germany

October, 1999

German Federal Agency for Civic Education

in co-operation with the

State Agency for Civic Education, Stuttgart, Germany

and the

Center for Civic Education, Calabasas, CA USA

INTRODUCTION

It has been said that high expectations breed deep frustrations. Perhaps the truth of that saying is attested in recent and more sober assessments of the phenomenon called globalization. The past decade was marked by unalloyed enthusiasm and unrealistic hopes for the emergence of a global village in which the world’s disparate and warring peoples would realize at last that they shared one small, vulnerable planet on which their destinies were linked. But there was no such epiphany. Instead there has been a growing, if disillusioning, realization that globalization is not a panacea for the world’s ills. Globalization has both advantages and disadvantages and it provides opportunities at the same time that it posits dangers, because globalization carries with it unanticipated, often contradictory and polarizing consequences.

As two thoughtful Australian legal scholars recently observed

This process of globalization is part of a ever more interdependent world where political, economic, social, and cultural relationships are not restricted to territorial boundaries or to state actors and no state or entity is unaffected by activities outside its direct control. Developments in technology and communications, the creation of intricate international organizations and transnational corporations. and the changes to international relations and international law since the end of the Cold War have profoundly affected the context within which each person and community lives, as well as the role of the state. 1

That globalization will affect for good or ill the lives of individuals throughout the world is a truism commonly accepted by scholars. David Rothkopf, a Columbia University Professor, writes that it is the first time in history that virtually every individual at every level of society can sense the impact of international changes. They can see it and hear it in their media, taste it in their food, and sense it in the products they buy. He predicts that during the next decade nearly two billion workers from emerging markets will have to be absorbed into the global labor pool. You are either someone who is threatened by this change or someone who will profit from it, but it is almost impossible to conceive of a significant group that will remain untouched by it. 2

Given the sweeping changes taking place in the world and their potential impact on the life of the individual, it is hard to explain why Americans have not been as attentive as they should to international and transnational developments. Americans, however, tend to regard all non-domestic concerns as foreign affairs or foreign policy matters. Just the use of the adjective foreign as a descriptor tells something about the American mindset. Recent research indicates that Americans lag behind residents of many Western nations in their awareness of key political actors, institutions, and events in the world. Further, the 1996 election did little to engage their interest or extend their understanding of the issues at stake. Candidates of both major parties for the presidency and the Congress largely ignored events beyond the nation’s borders. Unfortunately, as Richard Haass of Brookings Institute points out, the 1996 campaign only reinforced the impression that the world is a relatively safe place and that international concerns can continue to take a back seat to domestic matters. 3 There are no signs thus for that the campaign for the election in 2000 will be much different. In a recent interview, President Bill Clinton lamented that I think I have not succeeded yet in convincing the core majority of the country that there is no longer an easy distinction between domestic policy and foreign policy. Clinton then went on to warn his fellow citizens that sweeping transnational developments argue for a vigorous, engaged America at this moment, which will not last forever, when we are the dominant power of the world. 4

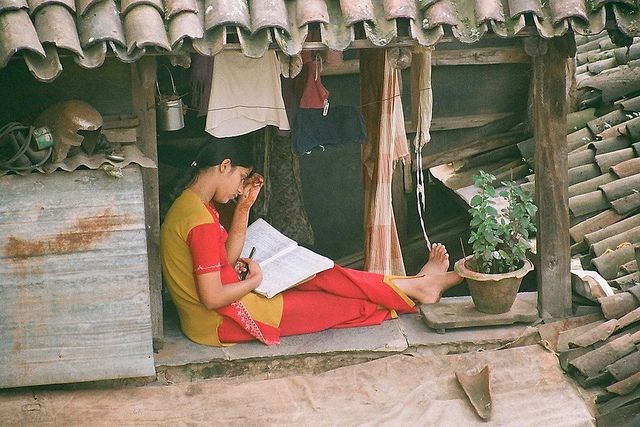

There is no doubt that all nations, not just the United States, need a vigorous and engaged citizenry cognizant of the fading distinction between domestic and foreign policy. In this era of globalization, the study of civics and government must include international and transnational dimensions. To restrict the study of civics and government to the domestic concerns of the United States, or to any other single country, is to fail to prepare students for the world in which they must live, work, and function as citizens.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to present a fully-developed curriculum or a set of standards which would address a study of global affairs adequate to the needs of students today. However, I would like to draw attention to what Richard Stanley, President of the Stanley Foundation, calls The Global Triad of business, civil society, and government. Profound changes in relationships among this global triad are altering the equation of global influence. 5 I would submit that awareness of these realignments is essential to students’ understanding of what globalization is and why it has meaning for them as individuals and as citizens.

THREE MAJOR CHANGES IN THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

Few would quarrel with the assertion that we are in the midst of unprecedented economic change and that change has profound implications for both political and education systems. Three major shifts can be identified. First, knowledge has replaced the economist’s classic denomination of land, labor, and capital as the chief economic resources. As Lester Thurow puts it in his latest book, Building Wealth: The New Rules for Individuals, Companies, and Nations The old foundations of success are gone. For all of human history, the source of success has been controlling natural resources-land, gold, oil. Suddenly the answer is knowledge. And then to drive home his point, Thurow adds, The king of knowledge, Bill Gates, owns no land, no gold or oil, no industrial processes. 6

Thurow’s book employs a central metaphor: the wealth pyramid. Whereas the Egyptian pyramids were built of stone, today’s wealth pyramid is built on knowledge. The need for improved education, therefore, is obvious. Not only must schools equip students with skills they will need in industries like microelectronics, computers, robotics, and biotechnology. They must equip them with knowledge of the world’s cultures and political systems that they will need to navigate successfully in a global environment.

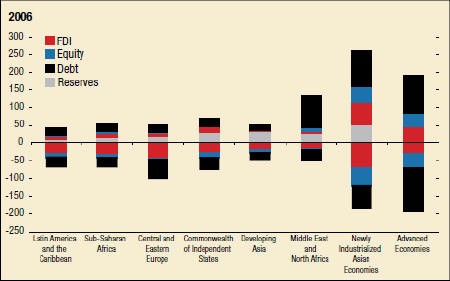

A second major change is in the nature of international trade. When they hear the words international trade, most people think of the exchange of goods. But today it is the movement of capital rather than the movement of goods that has become the engine of the world economy. The current financial and political crises, particularly in Asia, have revealed the flaws in the global financial system and made it the focus of much analysis and debate. George Soros insists that the the choice confronting the world today is whether to regulate global financial markets internationally to ensure that they carry out their function as a global circulatory system or leave it to each individual state to protect its own interests. The latter course will surely lead to the eventual breakdown of global capitalism. 7

Public policy debates about how best to stabilize the flow of international finance and keep the instability of financial markets under control are underway in the United States, as well as in other countries. The policy choices made will have profound implications for workers, taxpayers, and entrepreneurs in the developed countries, and they could have devastating effects on less developed countries on the periphery of the global economy.

A third major shift in the global economy is that multinational businesses are becoming transnational. Of the 100 largest economies in the world today only 49 are states, while the remaining 51 economies are transnational corporations. The role and power of transnational corporations (TNCs) have increased so much that Jeffrey Garten, Dean of Yale School of Management, believes that the spread of business across borders may be the most powerful force operating in the world. Today the world’s largest and most successful TNCs have budgets larger than those of many nation-states. TNCs treat the world as a single marketplace. They produce and deliver goods and services through a global division of labor which has meaning and consequences not only for American businesses and workers. There are consequences for all humanity ranging from environmental concerns and human rights to nuclear proliferation. 8

Transnational companies are not totally beyond the control of national governments, but, as Peter Drucker has observed, successful transnational companies see themselves as separate, nonnational entities. This self-perception is evidenced by something unthinkable a few decades ago: a transnational top management. 9

The United states has tried, as have some other governments, to counteract the tendency of transnational corporations to view themselves as beyond the control of national government. But attempts to extend American legal concepts and legislation beyond its shores, have met with limited success. Not only is the concept of anti-trust laws almost unique to the United States, the manner in which Americans deal with torts, product liability, and corruption has not proved to be effective with transnationals.

The growing political power and the overweening wealth of TNCs has triggered demands for economic, and legal rules that are accepted and enforced throughout the global economy. To date, however, international law and supranational organizations capable of making and enforcing rules for the global economy have not been developed.

THE RISE OF GLOBAL CIVIL SOCIETY

Despite persistent rumors of the imminent demise of nation-states, they remain the predominant actors in the world political system. Even so, the so-called absolutes of the Westphalian system-sovereign states each claiming exclusive control over a given territory and jural rights which all others were bound to respect-are being challenged. Challenges emanating from transnational corporations already have been discussed. But there is another potent challenge to nation-states posed by the rise of what is called global civil society. Global civil society is made up of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), and transnational networks (TNs). These non-state actors are individuals and groups with transnational interests that frequently have more in common with counterparts in other countries than with countrymen. NGOs and INGOs tend to be structured along traditional lines with headquarters, officers, membership fees, and the like. Networks, however, have no person at the top and no center. They are forms of organization characterized by voluntary, reciprocal, and horizontal patterns of communication and exchange. Networks stress fluid and open relations among committed actors working in specialized issue areas.

Today’s powerful non-state actors are not without precedent. There are historical forerunners to modern advocacy networks, including the Anglo-American antislavery movements and the international woman suffrage movement. But the explosive growth of supranational or global civil society is unprecedented. Jessica Matthews, Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, reports that both in numbers and in impact, non-state actors have never approached their current strength. And a still larger role likely lies ahead. Their financial resources and often more important, their expertise, approximate and sometimes exceed-those of smaller governments and international governmental organizations. Today’s NGOs deliver more official development assistance than the entire UN system. 10

Although the number of global nongovernmental groups has increased across all issues, approximately half of them are concerned with three central issue areas: human rights, the environment, and women’s rights. But it is the transnational environmental organizations that have grown most dramatically in both absolute and relative terms.

Because the organizations that constitute global civil society do not have power in the traditional sense of the word, they rely on the power of their information, ideas, and strategies to alter the information and value contexts within which states make policies. They try to persuade, but they also engage in arm-twisting and shaming.

A useful typology of tactics used by these non-state actors has been devised by Professors Keck and Sikkink. It includes

- Information politics or the ability to quickly and credibly generate politically usable information and move it to where it will have impact. The availability of easier and more rapid means of communications-e-mail, fax, telephone, and newsletters-has encouraged the spread of information politics.

Claims about rights are a central concern of many transnational nongovernmental organizations. This is understandable, because while governments are the primary guarantors of rights, governments also are their primary violators. When channels between the state and its domestic actors are blocked, domestic NGOs will try to bypass their state and search for international allies who can bring pressure to bear on their states from outside. This strategy was used in the case of South Africans who enlisted transnational support in their efforts to end apartheid. If a government is inaccessible or deaf to groups whose claims resonate elsewhere, domestic actors may seek international support to force the domestic government to pay attention. A case in point here was the plea of rubber tappers trying to stop encroachment by cattle ranchers in the western Amazon region of Brazil. 12

Until recently, international organizations were state-centered and state controlled. Now they have constituencies of their own, and they are bypassing the state to establish direct connections to the peoples of the world. This rise in global civil society has both advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, NGOs encourage citizen participation in policymaking. They can strengthen the fabric of the many still-fragile democracies. And they are quicker than governments to respond to new demands and opportunities. On the other hand, NGOs are special interests, albeit not motivated by personal profit. They tend to approach every public act or issue in terms of how it affects their particular interest. Jessica Matthews, reflecting on the explosive growth of global civil society, writes

A society in which the piling up of special interests replaces a single strong voice for the common good is unlikely to fare well. Single issue voters, as Americans know all too well, polarize and freeze public debate. In the longer run, a stronger civil society could also be more fragmented, producing a weakened sense of common identity and purpose and less willingness to invest in public goods, whether health and education or roads and ports. More and more groups promoting worthy but narrow causes could ultimately threaten democratic government. 13

GLOBALIZATION AND DEMOCRACY

Many people now believe that the advance of globalization is inevitable. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. has gone so far as to exclaim, Globalization is in the saddle and rides mankind. 14 Hyperbole aside, the critical question is: What are the implications of globalization for political and economic rights in particular and for democracy in general? World opinion is sharply divided about the correct answer to that question.

Those who view globalization negatively argue that it has political and economic ramifications which will prove detrimental to democracy. Whereas the Industrial Revolution created more jobs than it destroyed, the Technological Revolution threatens to destroy more jobs than it creates. Further, it will erect new and rigid class barriers between the well-educated and the ill-educated. Huge transfers of wealth from lower-skilled middle class workers to the owners of capital assets and to a new technological aristocracy will exacerbate the income disparities which already are evident in developed counties. In less developed countries such a transfer of wealth, and with it political power, could be devastating, and it could preclude progress toward democracy.

One strident critic of what he considers to be runaway global capitalism is, perhaps, a surprising critic. George Soros contends that the uninhibited pursuit of self-interest results in intolerable inequities and instability. Although I have made a fortune in the financial markers, I now fear that the untrammeled intensification of laissez-faire capitalism and the spread of market values into all areas of life is endangering our open, democratic society. 15

Similar worries are voiced by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. who writes:

The Computer Revolution offers wondrous new possibilities for creative destruction. One goal of capitalist creativity is the globalized economy. One-unplanned-candidate for capitalist destruction is the nation-state, the traditional site of democracy. The computer turns the untrammeled market into a global juggernaut crashing across frontiers, enfeebling national powers of taxation and regulation, undercutting national management of interest rates and exchange rates, widening disparities of wealth both within and between nations, dragging down labor standards, degrading the environment, denying nations the shaping of their own economic destiny, accountable to no one, creating a world economy without a world polity. Cyberspace is beyond national control. No authorities exist to provide international control. Where is democracy now? 16

Those who take a pessimistic view of globalization also argue that it is responsible for a withdrawal from modernity, the resurgence of identity politics and a retreat from democracy. They allege that when people believe that powerful forces, such as globalization, are beyond their comprehension and/or control, they retreat into familiar, comprehensible, and protective units. They congregate in ethnic, tribal, or religious enclaves. Globalization through the creation of international, multinational or regional trade and economic institutions can lead to a feeling of loss of political power by groups within states. The sense of loss of power, in turn, leads to a fostering of tribalism and other revived or invented identities and traditions which abound in the wake of the uneven erosion of national, identities, national economies and national state policy capacity. 17 The upsurge of religious fundamentalism is one case in point. The hostility of fundamentalism to freedom of expression and belief has ominous implications for democracy.

Globalism does have its defenders and they tend to see its potential for strengthening and extending democracy. Walter Wriston, former Chief Executive Officer of Citicorp and Chairman of the Economic Policy Advisory Board in the Reagan administration, is among them. He believes that we are living in the midst of the third great revolution in human history, the Information Revolution. Like the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions which preceded it, this revolution was sparked by changes in technology. With the invention of computers and advances in telecommunications, time and distance have been obliterated. However, instead of validating Orwell’s vision of Big Brother watching the citizen, the third revolution enables the citizen to watch Big Brother. And so the virus of freedom, for which there is no antidote, is spread by electronic networks to the four corners of the Earth. 18

William Meyer of the University of Delaware who has developed a quantitative model which attempts to measure the level of enjoyment of civil and political rights in developing countries has come to a conclusion akin to Wriston’s. He concluded that the technologies of communication and transportation that have made economic globalization possible also make it possible for the human rights ethos to spread and take root in all sectors of global civil society. Universal human rights represent nothing less than the ethical dimension of the emerging global culture. 19

Another argument advanced to support the contention of a positive relationship between economic globalization and democracy is that globalized economic institutions, including transnational corporations tend to demand that certain conditions obtain in a state before they are willing to invest. These conditions, sometimes called democratic governance requirements, lead to the protection of political rights. The treaty creating the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, for example, provides that it must advance democratic development. Other democratic governance requirements include acceptance of the rule of law, clear and transparent practices by government and local institutions, and procedures for international dispute resolution. The rule of law is particularly important to the protection of rights and the preservation of democracy. In a society governed by law, the legal system can be a means for people to defend themselves against bureaucratic abuse, commercial exploitation, and official lawlessness which all too often are the lot of the poor and the powerless.

CONCLUSION

There appears to be little doubt that globalization not only is a force to be reckoned with, but that its spread is to continue. Do its benefits outweigh its costs? There is, as yet, no certain answer to that question. Most scholars take a cautious, wait and see stance similar to this one which McCorquodale and Fairbrother offer

. It is possible to argue that there is a positive relationship between economic globalization and the protection of political rights. Certainly, the globalized economic institutions have been seeking to make the relationship a positive one by placing democratic governance conditions on investment and by taking some account of non-economic factors in their decision-making. However, the arguments that the relationship is a negative one are also strong. These arguments raise questions about the legitimacy of the democratic governance conditions and the seriousness with which human rights issues are taken into account by both global economic institutions and transnational corporations. It would appear that instead of creating order, the rule of law, and the protection of human rights, globalization can create conditions for disorder, authoritarian rule, and the disintegration of the state entity with consequent violations of human rights. 20

Globalization and its potential for advancing or inhibiting human rights and democracy is more than a subject for debate among academics. This powerful force is affecting the lives of individuals no matter where on this earth they live. Certainly we owe it to our students to help them understand the sweeping changes that are underway. We also need to help our students acquire the civic skills and the will necessary to direct globalization in ways that will protect and promote democracy.

1. McCorquodale, R. & Fairbrother, R. (1999, August). Globalization and Human Rights. Human Rights Quarterly. pp. 735-736. back

2. Rothkopf, D. (1997, Spring). In Praise of Cultural Imperialism? Foreign Policy. pp. 38-53. back

3. Haass, R. (1997, Spring). Starting Over: Foreign Policy Challenges for the Second Clinton Administration. The Brookings Review. pp. 4-7. back

4. Interview of President William Clinton conducted by Gary Wills and reported in Wills, G. (1999, March/April). Bully of the Free World. Foreign Affairs. p. 56. back

5. Stanley, A. (1999). Opening Remarks presented at the Stanley Foundation’s 34th United Nations of the Next Decade Conference. Adare Manor, Adare, Country Limerick, Ireland, June 13-18, 1999. back

6. Thurow, L.C. (1999, June). Building Wealth: The New Rules for Individuals, Companies and Nations. The Atlantic Monthly. p. 57. back

7. Soros, G. (1998-99, Winter). Capitalism’s Last Chance. Foreign Policy. p. 59. back

8. Garten, J. (1997, May/June). Business and Foreign Policy. Foreign Affairs. pp. 67-79. back

9. Drucker, P.F. (1997, September/October). The Global Economy and the Nation-State. Foreign Affairs. pp. 159-171. back

10. Matthew, J. (1997, January/February). Power Shift: The Rise of Global Civil Society. Foreign Affairs. pp. 50-66. back

11. Keck, M.E. & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, pp. 16-25. back

13. Matthews. supra note 10, p. 64. back

14. Schlesinger, A. Jr. (1997, September/October). Has Democracy A Future? Foreign Affairs. p. 10. back

15. George Soros is quoted in Schlesinger, supra, p. 8. back

17. Cerny, P.G. (1996). Globalization and Other Stories: The Search for a New Paradigm for International Relations. International Journal. p. 619. back

18. Wriston, W.B. (1997, September/October). Bits, Bytes and Diplomacy. Foreign Affairs. p. 172. back

19. Meyer, W.H. (1998). Human Rights and International Political Economy in Third World Nations: Multinational Corporations, Foreign Aid and Repression. Westport, CT: Praeger, p. 215. back

20. McCorquodale, R. & Fairbrother, R. supra, p. 758. back

Send comments regarding this page to web@civiced.org