Emerging Markets – Emerging Crisis or Media Hysteria

Post on: 3 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Emerging markets have been hemorrhaging this year and are now grabbing media attention. However, as the charts show, the decline in these markets and currencies has been taking place for some time now and is certainly not a sudden development. Question is: does the drop in these markets now present a real emerging threat to the rest of the globe, especially the stock markets of major developed economies? Let’s take a look.

First, What Is Going On?

Emerging markets are suffering significant capital flights out of their countries which is causing severe financial stress in various countries. We’ve seen this cycle many times over the last few decades in emerging market countries and the process looks something like this.

- An economic growth boom attracts foreign capital

- A positive feedback loop results in which rising foreign capital increases asset prices and furthers the economic boom which then attracts even more capital

- Inflows of foreign capital drive up the local currency and spur a consumption binge

- Growth becomes dependent on continued foreign inflows and is unsustainable

- Foreign appetite for the country becomes saturated and all that is needed is a change in sentiment to reverse the capital tidal flow

- Investors become spooked and a capital flight out of the country results

- This leads to a damaging positive feedback loop in which rising foreign capital outflows depress asset prices which depresses economic growth which leads to even more capital outflows and a declining currency

- A weakening currency leads to rising import inflation and causes central banks to intervene and raise interest rates to defend the currency

- This process continues until economic and financial imbalances are resolved

A recent example is in Turkey in which a weak currency is sparking inflation and leading the country’s central bank to hike rates:

Days late and many lire short. That’s the best way to describe the decision of Turkey’s central bank to boost overnight interest rates much more than expected, to 12% from 7.5%, and its one-week lending rate, to 10% from 4.5%.

Turkey’s problem is that it has been living in a credit bubble funded by foreign capital seeking high returns in a low-rate world. Unfortunately, capital inflows mainly financed a consumer boom that was not supportable by the Turkish economy.

As explains David Goldman, in his “Spengler” blog on Asia Times (atimes.com):

“Turkey was supposed to be the poster-boy for prosperity through Muslim democracy. Instead, it has become an object lesson in emerging market mediocrity, and its currency is collapsing because it pretended to be something better than that,” he writes.

“Turkey is in trouble because the Turks aren’t very good at anything in particular, but acted as if they were the next China. They borrowed vast sums from the international market against a glorious future that was never to be. Among all of the world’s big economies, Turkey has the worst current-account deficit, at nearly 8% of economic output, roughly where Greece was before its national bankruptcy. Investors reckoned that with high economic growth, Turkey would have no problem carrying its debt; what they did not take into account is that the growth itself was largely an illusion, a carnival of consumption and construction that depended on increasing debt in the first place,” he concludes.

Cases like these happen all the time in emerging markets as highlighted by past turmoil with the Turkish Lira.

Source: Bloomberg

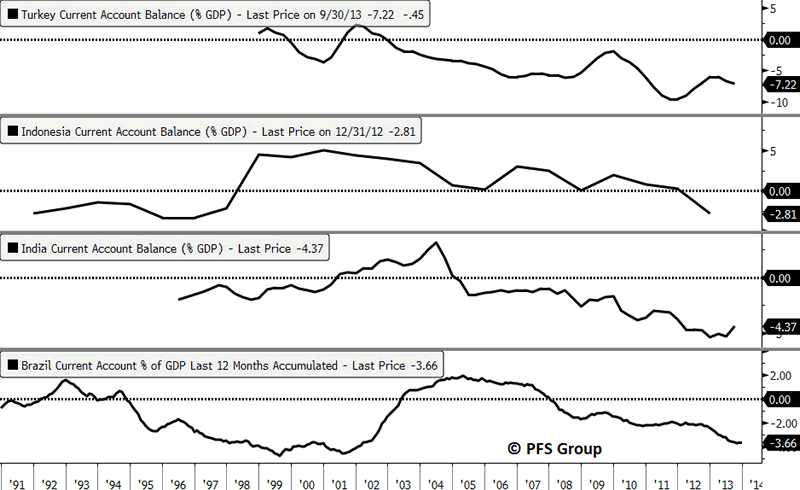

These emerging market crises stem from countries being susceptible to capital flights as a result of running current account deficits. Turkey is running a 7.22% deficit relative to its GDP but isn’t alone as the figure below highlights other countries that are suffering capital flights.

Source: Bloomberg

Turkey isn’t alone as India also suffers an ongoing capital flight, leading to weakness in its currency, which, in turn, has spurred higher inflation rates, slower growth, and stagflation since 2012.

Source: Bloomberg

Containment or Contagion?

Many times in the past the pressures occurring in emerging market countries have not led to a global contagion as occurred in the 1997 Asian Currency Crisis or the 1998 Russian Financial Crisis. but are rather short periods of country-specific turmoil. When a crisis develops it is always hard to determine the point at which a local crisis moves from being contained to contagion. “Contained” was the buzz word used to describe the U.S. subprime crisis in 2006-2007 until it was undeniable in 2008 that it was most certainly not contained. So then, the trillion dollar question is, how does one determine when a crisis is contained or developing into a contagion?

The best tool available is a wide-angle view of several markets by, quite simply, monitoring prices in equity markets and credit markets around the globe. If we are to see a contagion then we should see a domino of asset markets buckle under the weight of emerging market stress just as we did in 2008 with the U.S. subprime crisis or the Euro crisis in 2011-2012. As shown in the following figures, we are currently nowhere close to a contagion due to emerging market stress.

Below is a wide-angle view of credit default swaps (CDS, a measure of default risk) with key areas of the U.S. on the top panel and global regions on the bottom panel. As seen in the top panel, there is no visibly significant pickup of credit stress in the U.S. municipal bond market as measured by weak municipal districts (California, Indiana, New Jersey, New York), or by corporate debt issuers in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, or in debt issued by U.S. financial institutions. The recent move is a far cry to the deterioration seen in 2008.

Looking at Asia, Europe (both Eastern and Western), and emerging markets shows that stress levels are not as severe as 2008 nor during the Euro crisis of 2011-2012 as signs of a contagion currently remain absent.

Source: Bloomberg

Looking specifically at Europe, there is currently no sign of financial stress from emerging markets as credit default swaps (CDS) remain muted.

Source: Bloomberg

Looking at default risk for specific financial institutions also shows nothing like we saw in 2008 nor 2011-2012.

Source: Bloomberg

Looking at some specific emerging markets relative to some key developed nations does show elevated CDS levels in emerging market countries like Indonesia and Turkey, similar to what was seen in 2011-2012, but that period of stress was contained and so far the current period doesn’t appear to be anything more severe than then.

Source: Bloomberg

Contagion Canaries

Going forward the CDS readings for the above regions will need to be monitored for a break above levels seen during the 2011-2012 period. If they do, we may in fact be dealing with an emerging market crisis that is not only increasing in severity but also spreading globally. Given that the Markit CDS index for emerging markets currently rests at 336, a breach above 400 would exceed the highs in 2011 and be the highest reading in 5-years, suggesting things may be getting out of hand. I will be monitoring that level and alerting readers should it be exceeded. I will also be monitoring the price action of gold.

As stress in the global financial system increased during the 2008 crisis from 2009-2011, gold responded in kind. This can be seen by looking at a CDS composite I construced for the average CDS on G7 sovereign debt relative to gold. As global stress began to subside from 2011 to the present, so too did gold’s price. If gold begins to rally sharply this could be another indication of stress spreading in the financial system.Watching gold’s price action in the weeks ahead will be important.

Source: Bloomberg

The Emerging Market Bust May Be a Developed Nation Boom

The emerging markets are suffering relative to developed nations as a result of different inflationary trends and thus different central bank policies. High inflation rates characterize the emerging markets while the developed nations show the opposite. As such, developed-nation central banks can and are more accommodative than their emerging market peers. This can be seen in the image below which shows the consumer price indexes (CPI) for various countries normalized to 100 in 2007.

Source: Bloomberg

Not only are developed nations benefiting from accommodative central banks but they are also benefitting from weak commodity prices, something that characterized the strong stock market returns in the 1990s. Emerging market growth is often associated with higher commodity prices, which lead to rising import inflation and weaker economic growth. Consequently, periods of emerging market outperformance versus developed nations is often accompanied by strong commodity prices and vice versa. In the early 1990s, strong emerging markets and commodity gains witnessed modest gains in the S&P 500. However, when emerging markets and commodities peaked in the mid-1990s, the S&P 500 began to soar.

The opposite occurred in the early 2000s where emerging markets and commodities soared while the S&P 500 was essentially flat over the period.

Source: Bloomberg

The weakness in emerging markets and commodities that began in 2011 characterized a strong move higher in the S&P 500, similar to what occurred in the later 1990s.

Source: Bloomberg

Currently the financial press is working investors into a hysteria surrounding building stress in emerging markets. Stress in emerging markets is nothing new and pops up in specific countries on a yearly basis; however, there is always a risk that country-specific stress can spill over into a global contagion similar to what occurred in 1997-1998. The best way to determine when the risk spills over into something more dangerous is to monitor CDS readings globally as well as the price action in gold. If CDS readings remain muted then we are dealing with country-specific flare ups, but if they spike to levels higher than what has occurred over the last few years and gold surges we need to become more defensive.

With all that said, there is a bright side to the weakness in emerging markets and commodities for developed markets: a disinflationary stimulus similar to what occurred in the late 1990s and, more recently, since 2011. with the caveat that contagion does not result. Stay tuned.