Dr Gary Deleveraging is so profound and powerful that it has offset all monetary and

Post on: 22 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Dr Gary A. Shilling is one of those prescient economists that, at the very beginning of the financial crisis, sounded the alarm of deflation. At that moment, when the printing presses of the central banks seemed to be creating inflationary pressures, he argued that the massive deleveraging process of private, corporate, municipal and sovereign debt would create strong deflationary pressures and that deflation would prevail not only in his native United States, but in all developed countries, including those in the European Union. We asked him where the euro area stands today, what reforms should be carried out to fight deflation and support economic growth, and his views on the policy measures announced by the new Commission – in particular, Jean-Claude Junckers EUR 300 billion investment plan. He also shared his view on the recent referenda in Scotland and Catalonia and rising euroscepticism.

You are one of the prescient economists who, at the very beginning of the financial crisis, foresaw the danger of deflation. Could you briefly explain what deflation is and why we are under deflationary pressure today?

Deflation in its simplest terms means you have more supply than demand. In other words, the overall supply of goods and services exceeds the demand. You can get there in one of two ways, and I first defined this in a book I wrote in 1998 called Deflation, why its coming, whether its good or bad and how it will affect your investments, business and personal affairs. Then I coined a new distinction between good and bad deflation. If you have an increase in supply, thats good deflation, in other words its generally driven by productivity enhancing technologies and that was the case in the late 1800s in America when two very important new technologies reined. As a result, you had very strong GDP growth – an annual rate of 4% from 1876 to 1896 – which is unprecedented for a period that long, and yet we had deflation because supply outran demand. That was good deflation.

We also had good deflation in the 1920s. The roaring 20s were an exuberant period. Industrial production almost doubled between 1921 and 1929 and yet prices declined. Yet again you had two new technologies – mass produced automobiles, which brought with it roads, bridges and everything else that goes with cars; and the other one was electrification of homes and factories. When homes were electrified, that led to the invention of electric appliances and also radio, so it spawned new technologies. Now that is the good deflation of excess supply. The bad deflation of deficient demand is what was going on on a global basis in the 1930s. There was simply a collapse in incomes and they were not available to buy goods and services, so prices declined in the 1930s, starting the global depression. That was the bad deflation of deficient demand.

I coined a new distinction between good and bad deflation. If you have an increase in supply, thats good deflation, in other words its generally driven by productivity enhancing technologies () The bad deflation of deficient demand is what was going on on a global basis in the 1930s.

What do you see today: good or bad deflation?

Its fair to say that we have some of both. We certainly have excess supply – part of that is new technologies like robotics, biotechnology, the internet and so on; the other part is the result of globalisation, which has opened up huge capacity in China and other countries. However, we also have deficient demand, since, despite all the monetary and fiscal stimuli, the economies of the world are growing very slowly. This is because of global deleveraging which is going on after a period of exuberance and leveraging up, simply adding a lot of debt.

In my most recent book from 2010, The Age of Deleveraging: Investment Strategies for a Decade of Slow Growth and Deflation. I pointed out that normally it does take a decade to work off these excesses. Thats where we are now. Regardless of the immense monetary and fiscal stimuli, what have you got? In the USA, 2% GDP growth, and in the euro area much less. Weve been on the cusp of a third recession since 2007. Deleveraging is so profound and powerful that it has offset all the monetary and fiscal stimuli.

It seems that the stimuli have not been very successful in supporting demand, but share markets and equities seem to be growing.

Yes, monetary and fiscal stimuli have pushed up asset prices, specifically stocks, but it hasnt really convinced the stockholders, who are basically high-income people, to go and spend money. The Federal Reserve hoped that that would be the case but it didnt work. The central banks can raise and lower interest rates, they can buy and sell securities, but it never got past the stage of raising asset prices because high income people dont tend to adjust their spending habits depending on whether asset prices go up or down, so you never got beyond that.

All this quantitative easing has not done any good. There were many early on who said were going to have rampant inflation from all this, particularly the quantitative easing, and gold is the only answer – well look what happened to those people. Gold got to almost USD 1 900 per ounce and is now below USD 1 200. Things went the other way for them. I think it shows you the power of this deleveraging, and all of this contributes to a deflationary climate.

Within this deflationary climate, public authorities try to support economic growth by increasing spending. Jean-Claude Juncker, the newly appointed President of the European Commission, has proposed a EUR 300 billion investment plan. Do you think such a plan would help the economy?

It depends a lot on where the spending is. If the spending is strictly on support for consumer income, it doesnt have much follow on effect. If it goes into infrastructure it probably does. Improvements to roads, bridges, digital networks and communications in general do have a lasting effect, but simply supporting consumer spending probably doesnt. Of course, the other aspect of this, particularly in Europe, is that fiscal stimuli will then cover up the need for structural reform. It detracts attention from it. Now, this is the argument from what I call the Teutonic North, led by Germany, as opposed to the Club Med south led by France, Italy and Spain.

The argument which would be made by the Germans is that fiscal stimuli will simply detract from the need for reforms, in particular labour market reforms. I would say that you have a situation in the euro area now where the economy is slipping into a third recession. Mario Draghi, head of the ECB, has made it very clear recently that he doesnt see monetary policy as the sole generator of growth, and I think he is right.

You can pump money into the economy, but if banks are reluctant to lend because they have a lot of regulatory problems, the money just piles up as excess reserves. Or in the case of the euro area, all the money that was pumped in towards the end of 2011 – a lot of that has been repaid, and of course Draghi wants to get it back to where it was in the spring and summer of 2012, which means another trillion euros out there in loans. But what Draghi has recently said is we need help on the fiscal side; we cant do it from the monetary side alone, despite the objections of Germany and other Teutonic North countries.

Arent fiscal and monetary policies necessary not only to support the economy, but also to avoid further social instability and euroscepticism?

We are approaching that turning point where we will also see a social reaction, not only in southern Europe, in the periphery, but also at its centre. People will take to the streets, and nobody wants it to get to that stage so there is tremendous pressure on governments to do something, to try new measures to restore growth. I dont think there is a lot that can be done until the leveraging is over, and if history is any guide were six years into it and we have another four to go, and at the rate that the excess debts are being worked out it could take more than another four years, but in the meantime politicians are in a very difficult position. Eurosceptic parties have appeared to be much stronger following the European elections in May and are still growing – not only in France, Italy and Spain, but also in the UK and Germany. It doesnt look to me like it has reached a dangerous level yet, but its certainly disconcerting. David Cameron has had to deal with a lot of attention going to UKIP. It may be a small group, but its a thorn in his side that is hard to ignore.

Economic inequality and bigger regional disparities have given rise to movements demanding regional autonomy or secession. What do you think of the recent referendum in Scotland and the consultation in Catalonia?

To me these kinds of developments make absolutely no sense. I think when youre in a weak economic situation you want to see bigger and stronger countries, not smaller splitting groups. Look at the Balkans. Theres a term in English called balkanisation which describes the splitting of countries after the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. What you end up with is a bunch of tiny countries that are all very vulnerable.

The USA is very lucky as a country, as it developed largely after two important events. The invention of the railroad allowed the movement of people and goods easily across the country, and Lincolns decision to hold the country together after the civil war, regardless of the tremendous cost, laid the foundation for our unity. That was the most traumatic event in American history, but as a result we have one country.

There may be regional differences, but theyre tiny compared to Europe. We are one country; we dont have places like Arizona saying they are going to become their own country, no-one thinks seriously about it. Were very lucky historically, while in Europe you can travel 100km and you have a whole different culture, which is great for Americans as tourists coming to see very different societies and economies, but its hell for running economies. Thats what theyre trying to overcome with the euro, but its very difficult.

If we turn back to current European affairs and the policy proposals to tackle the crisis, one of them was to exclude Structural Funds co-financing by national and regional governments from debt calculations. What do you think about such proposals to rewrite the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact?

Well, if you throw out enough bad, you can make anything look good in comparison. Lets say clearly that its like the bank. All the bad loans are put into the bad bank. You can act like it doesnt exist, but it does. You cant write them off, you have to deal with them, and youve got to bail them out. I think in this case my preference would be not to take the route of redefining rules in this way. In the case of a country like Italy, with a government debt sitting at 134% GDP, if you keep co-financing of European funds out of debt calculations youre excluding a lot of debt, but the debt still exists.

In the case of a country like Italy, with a government debt sitting at 134% GDP, if you keep co-financing of European funds out of debt calculations youre excluding a lot of debt, but the debt still exists.

I would rather just call spending what it is, especially if the decision is that the economic situation is so weak that we will rely on government spending. Accumulating spending and debt may not be efficient in the long run, but at least it satisfies a public urge right now. I would rather see politicians deal with it, and say that if the deficit is going to be under 3% of GDP in the long run, its going to be 6% or 8% in the short term, rather than trying to redefine it and act as if you have to rediscover fiscal virginity, when in fact you have run up a huge deficit. I just dont see the logic of inventing new rules to hide reality.

Another problem is that such proposals invite supposedly temporary expedients to become permanent. In other words, I suspect that this idea of a primary budget deficit, without expenditure linked to EU funds-financing, is going to be long lasting. It was introduced with the idea that its a short term problem, due to a financial crisis and a way to say that countries have problems right now, and the government debts of the previous administration dont have to be worried about. In the long run, that debt is still there, and if it isnt addressed it will be there forever. I look at debt in relation to GDP – the precise number doesnt matter, but its relevant to the size and competitiveness of the economy. If you restore rapid growth, and debt-to-GDP comes down, then fine. However, the risk is that they simply throw this out of the equation, and if the primary debt becomes the rule, politicians will act like none of this debt really exists.

So long-term reforms and competitiveness are much more important?

Yes they are, but you have to realise that Im looking at this with an American bias, and this is an Anglo-Saxon approach. I think it is pretty close to the approach of the Teutonic North in the euro area, although from an American standpoint the Germans are way to the left in terms of social programmes and this goes back to Bismarck. He bought off the socialists by introducing the social state. From our standpoint even Germany is a lot further left than we are. Still, the whole idea here is what do you believe is important? Do you believe it is free enterprise or do you believe what the French do, that it is the government that is at the centre of decision making, including in the economic sphere, in which case you get less excited about the reforms that were screaming about.

What do you think of the view that the euro is too strong?

If you look at history, the euro came in in 1999. Between then and now, if Greece, Portugal and some other countries like Italy had not been in the Eurozone, they would have devalued two or three times, maybe more, because that was the normal way to address the issue of competitiveness and the fact that costs were high and productivity was low compared to their trading partners and competing countries.

They come to a point when they devalue and start all over, wiping out debt and bond holders, but it doesnt work that way today. These countries cant do that now, and that creates a serious problem for their competitiveness. What we have had in response to that is internal devaluations. For instance in Greece, wages are down a third from what they were during the crisis. Basically they cannot devalue the common currency, so they must cut their labour costs to deal with it, via internal devaluation. Its kind of a painful exercise, but its a way of achieving the same goal.

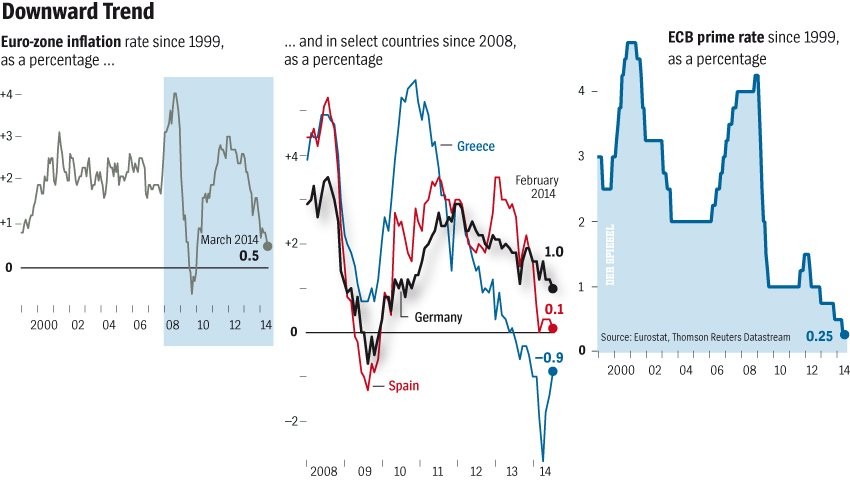

On a euro-wide basis there is now a very deliberate attempt by Draghi to trash the euro. They dont say that, but they want it because they think the earlier strength in the euro pushed down import prices, and that meant any competitors to import and service production had to reduce their prices or go out of business. This is what the ECB seems to believe, and that is the reason their year-on-year consumer price index (CPI) was 0.4% in October and they want 2% like all the other central banks. They wanted it high enough that a glitch couldnt cause deflation.

Finally, you are a very keen beekeeper. What has this activity taught you in relation to the economy and forecasting?

I am looking at a glass case at the other end of my office which has a pair of bee gloves in it. These are gloves which have padding to stop them stinging you. The idea is that bees stings cant get through the gloves, but those ones are covered with little dots, which are stings. I was wearing them a few years ago around November, and it was a rainy day, which makes the bees mad. It was getting late in the day, and I had some things I had to do in the beehive, so I had no choice. The canvas of the gloves was wet, so it stuck to my skin, which meant the bees could get through and sting me. There must be at least 100 in each glove… I look at those gloves when were having trouble analysing the current economic situation or portfolios here, and I tell myself that life can be rougher, and it has been rougher. It puts things in perspective.

Interview by Branislav Stanicek

Dr Shilling is President of A. Gary Shilling & Co. Inc. Before establishing his own firm in 1978, Dr Shilling was Senior Vice President and Chief Economist of White, Weld & Co. Inc. Previously, he set up the Economics Department at Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith at age 29, and served as the firms first chief economist. Prior to Merrill Lynch, he was with Standard Oil Co. (N.J.) (now Exxon), where he was in charge of U.S. and Canadian economic analysis and forecasting. Twice, a poll of financial institutions conducted by Institutional Investor magazine ranked Dr Shilling as Wall Street’s top economist. Dr Shilling was also named No. 1 Commodity Trader Advisor by Futures magazine. In 2003, MoneySense ranked him as the third best market forecaster, behind Warren Buffett. He has published numerous articles and books, mainly on inflation and deflation. In late 2010, John Wiley & Sons published The Age of Deleveraging: Investment strategies for a decade of slow growth and deflation . which spent some time atop the Amazon.com best-seller list. His firm publishes a monthly newsletter, Insight. Dr Shilling earned his master’s degree and doctorate in economics at Stanford University. He is also an avid beekeeper.