Dollar Depreciation

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Dollar depreciation is thought by many to be a good method of increasing output, investment and employment, while at the same time helping to reduce our current account deficit. At first glance, it seems obvious; a weaker dollar will make U.S. exports comparatively cheaper and thus increase output, investment and employment. In Reality, however, the theoretical models empirical evidence are much more complex. In this paper, I will discuss theoretical arguments in favor of and against a policy of dollar depreciation, as well as provide empirical evidence of its effects. I will discuss dollar depreciation in terms of output, investment, employment, the current account and inflation. In the end I will use this economic theory and empirical evidence to argue that the risks of dollar depreciation outweigh the benefits and it is therefore not a desirable policy.

Theoretical and Empirical Arguments for Dollar Depreciation

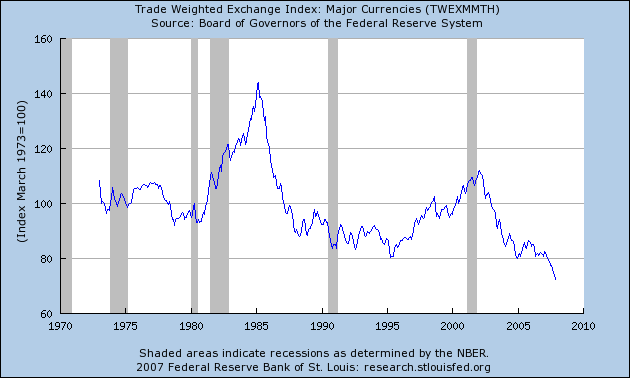

One argument is that dollar depreciation relative to other currencies will increase output and profits for firms that export goods. The simplest form of this argument states that a weaker dollar will make American exports comparatively cheaper and therefore, foreign consumers will demand more U.S. exports. This increased demand for exports will increase output for American firms. For example, say the dollar depreciates relative to the euro. Where consumers could once buy $1.10 for one euro they can now buy $1.20. This dollar depreciation can be seen in Figure 1 in the appendix. Suppose that consumers in Europe could purchase an American DVD player for 100 American dollars. At the previous exchange rate it would have cost them 90.91 (100/1.10) euros to buy the American DVD player. Now, after the depreciation of the dollar, assuming the domestic price stays constant, they can buy the American DVD player for 83.33 (100/1.20) euros. This decrease in price, will cause European consumers to demand more American DVD players. Thus, output for American DVD player manufacturers will increase.

Richard Clarida of Columbia University provides a more complex model. He states that there are two channels in which exchange rate changes can change the profits of an exporting firm; a valuation channel and volume channel. The profits through these channels depend upon the extent to which a real depreciation is passed-through to foreign currency prices. That is, the extent to which foreign currency prices reflect the real depreciation of the dollar. If none of the real dollar depreciation is passed-through, profits per unit increase while the number of units sold remains the same. Conversely, if all of the depreciation is passed through, profits per unit stay the same while the number of units sold increases (Clarida, 178). This can be shown using the simple example mentioned earlier. If the dollar depreciates from $1.10 to $1.20 per euro, but none of the real depreciation is passed through to foreign currency prices, European consumers will continue to pay 90.91 euros for a DVD player, but will demand the same amount. However, the real value the firm will receive from the transaction will be equal to $109.09 (90.91*1.20). Although their unit sales will not increase, they will be earning more per unit and thus profits will increase. On the other hand, if the dollar depreciates from $1.10 to $1.20 per euro and all of the real depreciation passes through to foreign currency prices, European consumers will pay 83.33 euros per DVD player. As mentioned earlier, the lower price of DVD players will cause European consumers to demand more. The firm’s profit margins will remain the same, but they will sell more units and thus, profits will increase. Therefore, a real depreciation of the dollar should boost the profits of US manufacturers regardless of whether pass-through is complete, partial or non-existent (Clarida, 178).

Clarida used two different empirical approaches to estimate the relationship between exchange rates and U.S. manufacturing profits. The first was to estimate a single equation, error correction model which related profits and 5 other variables (including the exchange rate). He found that the relationship between profits and exchange rates is statistically significant. Furthermore, he found that during the period from 1980-1985 when the dollar was strong, dollar appreciation resulted in 25% less manufacturing profits. Furthermore he found that during the period from 1985-1990 when the dollar was weak, dollar depreciation resulted in 30% more manufacturing profits. His second approach found that a 1% depreciation in the dollar caused a 1% increase in manufacturing profits (Clarida, 178). These results provide strong evidence that a depreciation in the dollar could result in an increase in U.S. manufacturing profits.

Furthermore, assuming the real depreciation of the dollar passes through to foreign currency prices, the degree to which demand for U.S. exports increases is determined by the elasticity of demand for U.S. exports of foreign countries. For example, if a dollar depreciation causes prices for us exports to fall 10% in Japan and the Japanese elasticity of demand for U.S. exports is -.8 the quantity demanded for U.S. exports will increase 12.5%. However, if their elasticity of demand is -1.2, quantity demanded for U.S. exports will increase only 8.3%. Either way, the dollar depreciation relative to the Japanese yen will increase U.S. exports to Japan, but the extent to which they increase is dependent upon Japanese elasticity of demand for U.S. exports.

Additionally, the degree to which exporting industries can benefit from a weaker dollar is dependent on how open it is to international trade. Obviously, the more open the firm is to international trade, the more it will benefit from a weaker dollar. Firms in the U.S. have become increasingly more open to trade over time and therefore, depreciation of the dollar will probably have a more beneficial impact on U.S. exports than it would have in 1970 (ceteris peribus).

Another argument in favor of dollar depreciation is that a weak dollar will increase investment in U.S. firms. The strongest effects of dollar depreciation on investment in the U.S. occur in manufacturing durables and non-manufacturing sectors. As explained earlier, dollar depreciations could lead to increased profitability for U.S. exporting firms. This increased profitability will cause these firms to invest more capital in new plants and equipment. Furthermore, depreciations will lower the costs of production in the domestic economy. It will become cheaper for firms to produce in the United States. Therefore, with a dollar depreciation, firms will be more willing to invest additional capital for production in the United States as opposed to foreign markets. Entrepreneurs, seeing the low costs of production and the increased profitability of these industries will be more likely to enter these markets. Therefore, depreciation of the dollar relative to other currencies should increase investment in U.S. firms.

Furthermore, it follows that with increased investment will come more job creation. When firms see increased profit potential they will invest more and invest in the U.S. Thus, more jobs will be created. If new firms are entering the market and existing firms are increasing their production due to increased demand for exports and lower costs of production they will need to employ more people. And because the weaker dollar makes it comparatively cheaper (ceteris peribus) to produce in the United States, firms will create more jobs in the U.S. It is obvious that this is good for the U.S. The lower the unemployment rate, the better.

Finally, a weaker dollar may help the balance of payments account. It will increase exports by making them comparatively cheaper in foreign markets. Furthermore, it will discourage imports. U.S. consumers will be able to afford fewer imported goods because they will be more expensive due to the weaker dollar. Going back to the first example of a depreciating dollar against the euro, say the DVD player manufacturer is instead a European firm. Previously, it took $1.10 to buy one euro and thus, a DVD player that cost 100 euro would cost an American $110. After depreciation it would cost $1.20 to buy one euro and thus, assuming European prices of DVD players remained constant, it would cost $120 to buy a European DVD player. U.S. consumers would demand fewer European DVD players. Furthermore, this would be true of goods from every country whose currency appreciated against the dollar. Hence, a weaker dollar will decrease the demand in the U.S. for imports. Increased exports and decreased imports will either cause a current account surplus, or lessen a current account deficit.

Currently, the United States is the world’s largest net debtor. This is mostly due to our policy of running large current account deficits over the past 30 or so years (McKinnon). Ronald McKinnon of Stanford University points out two major problems with continuing to run current account deficits. First, it leads to excessive borrowing and declining creditworthiness on the part of individual American households and some firms (McKinnon). This debt could lead to increased bankruptcies and as a result could cause decreased consumer spending. Second, is a threat of protectionism. Foreign saving can only be transferred to the U.S. by increased American expenditures and decreased American income. Thus, there will be a higher level of imports and fewer exports. And due to, heavy state intervention and protectionism for agriculture and some services around the world, it is the industrial sector that typically bears the brunt (McKinnon). Thus, American industries will have a harder time competing with their foreign competition. A weak dollar can help to decrease or eliminate the current account deficit and thus, alleviate these negative effects.

However, the effects of dollar depreciation will not immediately take effect. Some argue that currency depreciation will improve the current account in the long-run, but will worsen the current account in the short run. As time passes, the current account deficit shrinks and eventually becomes a surplus. This happens, in part, due to the currency contract effect. This happens when import and export decisions are made before a currency depreciates. Because these decisions are made before depreciation, the quantity of imports and exports will not reflect the change in the value of the currency. Prices of imports will increase and prices of exports will remain unchanged. For example, say a manufacturing company in the U.S. orders a given amount of steel from a foreign source because at the current exchange rate it is cheaper than domestic steel. Before it is paid for, the dollar depreciates relative to that country’s currency. They are going to be stuck paying the higher price when they would have either ordered less or bought from a domestic source had they not made the agreement. Thus, the value of imports on the U.S. current account will rise and will result in a larger current account deficit in the short-run. In the long run, after new contracts are signed, imports will fall and exports will rise to lessen or eliminate the current account deficit.

Theoretical and Empirical Arguments Against Dollar Depreciation

One argument against depreciating the dollar is that it will, contrary to what supporters of depreciation say, decrease output. Proponents of dollar depreciation say that the lower relative price of U.S. export in foreign markets will increase demand and thus increase U.S. output. However, dollar depreciation will cause the real income of U.S. households to decrease. This is because their purchasing power will decrease. They will be able to buy fewer items with their dollar. This may reduce domestic demand for U.S. products and thus, output for U.S. firms. Although firms may be able to sell more goods abroad, they will not be able to sell as many domestically. If the decrease in domestic sales is greater than the increase in foreign sales, dollar depreciation will have a negative effect on the output of U.S. firms.

Furthermore, dollar depreciation will increase the cost of imported inputs in production. This will cause an increase in marginal cost of production and therefore will hurt the firms profitability. For example, say a firm that uses a substantial amount of natural gas in the production of their product, and is producing in the U.S. When the dollar depreciates relative to other currencies, the cost of importing the natural gas will increase. This firm can not substitute for domestic natural gas and therefore must import natural gas at the increased price. The costs of production will thus, increase. Although they will be able to export more units, their profit will be lower due to the increased cost of production. This could lead to contractions in supply.

Empirically, decreased output in the aggregate due to depreciation of the dollar has proven to be true. The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City looked at data from the second quarter of 1961 to the fourth quarter of 1987. They found that after a decline in the dollar, there was a boost in aggregate output in the short-run. But after about the 8th quarter, aggregate output returned to its original level. And in the long run, aggregate output declined by about 3 percent. This is probably because of higher imported prices and their implications for supply. That is, higher prices of imported inputs increase the marginal cost of production and cause supply to fall.

Critics of dollar depreciation also argue that a weak dollar will lead to decreased investment in the United States. First, as explained above, a weak dollar may decrease output and thus profits for firms in the U.S. Thus there would be decreased investment, probably disinvestment, in new plants and equipment. Furthermore, fewer firms would enter the industry. Second, a weak dollar can hurt non-traded goods sectors. If demand for traded goods, that is, exported goods, increases due to a dollar depreciation, capital may move from non-tradeables to tradeables, thus hurting the non-tradeable industry. More significantly, a dollar depreciation can cause investors to reallocate their investment portfolios. For example, say the dollar depreciates against the yen, investment in yen denominated securities would then be more attractive. The stronger yen would make the values of Japanese investments more valuable, thus investors may reallocate their capital from American investments to Japanese investments. Further, it will redistribute wealth to investors already in the market. Holders of Japanese investments will see an increase in their wealth, while holders of U.S. investments will see a decrease in their wealth. Thus, dollar depreciation can lead to decreased investment in the United States.

Empirical evidence has proven this to be true. Linda Goldberg estimated the effects on Exchange Rates and Aggregate Investment of manufacturing, manufacturing durables, manufacturing non-durables, and non-manufacturing. She found that, exchange rate appreciations (depreciations) were associated with investment expansions (contractions) (Goldberg, 581). This relationship was especially significant in the 1980’s. Furthermore, manufacturing non-durables and non-manufacturing industries were more significantly affected by exchange rate fluctuations. It would appear then, that when looked at empirically, dollar depreciation has an adverse effect on U.S. investment.

As discussed earlier, proponents of depreciation argue that a weaker dollar will create jobs. Empirically, however, this does not hold. National Bureau of Economic Research studied the effects of dollar depreciation on job creation and job destruction. They found that from 1973 to 1993 the job creation rate in manufacturing was 8.8 per 100, while the job destruction rate was 10.2. Thus, the net decline in jobs was 1.3. Furthermore, they found that the job destruction rate was related to appreciations in the dollar. For example they found that during the dollar appreciation from 1982 to 1986 the job destruction rate was 12.2 percent, which was well above the average (10.2 percent). At first glance this may seem to support the view that dollar depreciation can create jobs. However, when they estimated a regression formula, they found that while, job destruction is sensitive to exchange rate movements, job creation is not (Goldberg). They also found that job destruction increases with increases in the dollar, but job destruction does not decrease when the dollar depreciates. That is, not only does job creation not rise when the dollar depreciates, job destruction doesn’t even fall. It would appear then, that depreciating the dollar relative to other currencies is not an effective way to create jobs. Although this study does show that appreciation of the dollar will be harmful in that it causes job destruction.

Another argument against depreciating the dollar is that it can cause inflation. Indeed, after the dollar was depreciated in 1970-73 and 1978-80 inflation soared (Dornbusch, 26). Furthermore, Goldberg found there to be an inverse relationship between the dollar and inflation. That is, when the dollar depreciates, Inflation increases. For example, between 1980 and 1984 the dollar rose 58 percent while inflation fell 66 percent. Furthermore, Goldberg found that, the shock to the dollar leads to a permanent increase in the price level. This increase is roughly 5 percent over 4 years. Finally, Goldberg found that dollar depreciation causes real wages to fall. Dollar depreciation thus causes price levels and inflation to rise while at the same time reducing real wages. Americans will be making less money, while at the same time having to pay higher prices for goods and services. Dollar depreciation may therefore not be a good way to boost the economy.

Given these two conflicting theoretical and empirical arguments, is dollar depreciation a good policy to spur economic growth? Both sides have convincing arguments. Generally, merchandizing output should increase, however it is dependent on so many variables, (i.e. elasticity of demand, openness to trade, domestic changes in price level and demand, etc.) that it is hard to predict with certainty whether output will increase or decrease with a weaker dollar. It seems that, if all other variables remain the same, output and profits will increase. However, all other variables rarely remain the same. It is then necessary to look to empirical evidence. Clarida’s empirical evidence in support of depreciating the dollar showed that merchandizing firms have seen increased profits as a result of dollar depreciation. However, Goldberg’s evidence showed a short-term boost in profits in the aggregate followed by a fall in the long term. One would have to say then, that if the goal is to provide a quick, short boost to output dollar depreciation is appropriate, but if the goal is long term sustainability another approach would be preferable. Furthermore, empirical evidence shows that dollar depreciation does not increase the output of non-manufacturing or non-exporting firms. Hence, even if output does increase for exporting manufacturing firms, benefits will be limited to that sector in terms of output growth.

Investment implications rely heavily on what happens to output and profits of the firm. It can be a dangerous policy if output, in fact, does not increase as a result of a weak dollar. A weak dollar will cause investors to reallocate their investment portfolios outside of the U.S. Unless there is an incentive to invest in U.S. firms, such as increased profitability, the capital account will face a deficit. Combine that with a current account deficit, and the results could be disastrous. Empirical results show that a deprecation of the dollar has resulted in decreased investment especially in the manufacturing of non-durables and non-manufacturing sectors. Therefore, if increased investment is the target, dollar depreciation is not the right policy. It is risky and has not worked in the past.

Empirical evidence further shows that dollar depreciation is not an effective tool to create jobs, although the evidence doesn’t show that it will decrease employment. It should be noted, however, that dollar appreciation has been linked to job destruction.

Further empirical evidence has shown that dollar depreciations can lead to increased inflation, higher prices, and lower real wages. And therefore may, in fact, hurt our economy.

As discussed earlier, our current account deficit is a problem, and must be dealt with, but devaluing the dollar is not the best method. First of all, even if output does increase, it will have a lagged effect on the current account and will hurt it initially. Secondly, empirical evidence shows that output is actually likely to decrease in the aggregate in response to a depreciated dollar, and thus have an adverse effect on the current account. Though the theoretical arguments in favor of depreciating the dollar are somewhat convincing, empirical evidence is overwhelmingly against the idea. The U.S. should look for alternative ways to increase output, investment, and employment, and deal with our current account deficit.